William Hall Burnett in Middlesbrough 1886 says “We may fairly claim that hereabouts English Literature had its first beginning.” He begins with Aneirin and Y Gododdin (spellings vary in different texts)

“Aneirin [aˈnɛirɪn] or Neirin was an early Medieval Brythonic poet. He is believed to have been a bard or court poet in one of the Cumbric kingdoms of the Old North or Hen Ogledd, probably that of Gododdin at Edinburgh, in modern Scotland. From the 17th century, his name was often incorrectly spelled “Aneurin”.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aneirin William Hall Burnett spells it the incorrect way here.

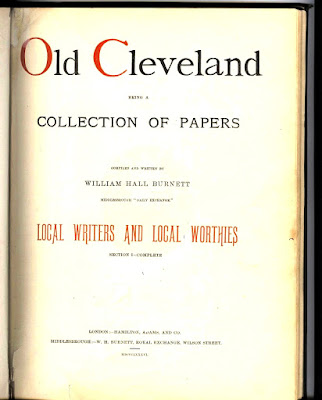

William Hall Burnett – poet and editor of the Middlesbrough Daily Exchange – wrote, in his book Old Cleveland – Local Writers and Local Worthies in 1886 on the subject of the Celtic bard Aneurin – (Alternatively spelt Ane

“The warrior bard, Aneurin, must, in the old Celtic days have been resident within this immediate district, so that we may fairly claim that hereabouts English Literature had its first beginning. It is a least a fair conjecture that the first of English epic poems were strung together, line by line and verse by verse by a bard who, wandering amongst the valleys of the Swale, might now and again visit the fair plain of Cleveland in the golden east. To Aneurin is ascribed the important fragment of celtic literature, The Gododin, being a lament for the dead who fell in the battle of Cattraeth, identified with Catterick in Yorkshire, where Cymry met the advancing and invading Teutons at the ‘confluence of rivers’ and fought with them unsuccessfully for seven days….“

Also from W H Burnett

This is where the Cymry met the advancing and invading Teutons at the ‘confluence of rivers’ and fought with them unsuccessfully for seven days, being at length worsted with fearful slaughter. Of this battle The Gododin tells us –

“The warriors marched to Cattraeth with the day;

In the stillness of night they had quaffed the white mead;

They were wretched, though prophesied glory and sway

Had winged ambition. Were none there to lead

To Cattreath with loftier hope in their speed?

Secure in their boast, they would scatter the host

Bold standard in hand; no other such band

Went from Eiddin as this, that would rescue the land

From the troops of the ravagers. Far from the sight

of home that was dear to them, ere they too perished,

Tudvwlch Hir Slew the Saxons in seven days fight,

He owed not the freedom of life to his might,

but dear is his memory where he was cherished,

When Tudvwlch amain came to that post to maintain,

By the son of Kilydd, the blood covered the plain.”

PDF Click the arrow to enlarge and read or download free.

Read the poem here http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/9842?msg=welcome_stranger

Wiki https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y_Gododdin

I’m not sure where I sourced this from in 2005 when I did the original post but it’s interesting –

“Gododin

that the Britons lost the battle in consequence of having marched to

the field in a state of intoxication; and it must be admitted that

there are many passages in the Poem, which, simply considered, would

seem to favour that view. Nevertheless, granting that the 363

chieftains had indulged too freely in their favourite beverage, it is

hardly credible that the bulk of the army, on which mainly depended

the destiny of the battle, had the same opportunity of rendering

themselves equally incapacitated, or, if we suppose that all had

become so, that they did not recover their sobriety in seven days!

The fact appears to be, that Aneurin in the instances alluded to,

intends merely to contrast the social and festive habits of his

countrymen at home with their lives of toil and privation in war,

after a practise common to the Bards, not only of that age, but

subsequently. Or it may be that the banquet, at which the

British leaders were undoubtedly entertained in the hall of Eiddin,

was looked upon as the sure prelude to war, and that in that sense

the mead and wine were to them as poison.”