Welcome to Artsrainbow. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

John Wesley Hackworth 1820 – 1891 – An Introduction

Engineer, Inventor and a Son of Timothy Hackworth.

“I saw the Stockton and Darlington railway opened, was brought up upon it, knew every horse, and driver, every locomotive driver, and fireman, every director, nearly all the shareholders, and every noteworthy incident that occurred thereon for the first 20 years; and if any living man knows anything of its history, and working, I am the man!”

Samuel Holmes – a grandson of Timothy Hackworth wrote, in the 1920’s,

“It is hoped that Mr Albert Hackworth (the son of John Wesley Hackworth and grandson of Timothy Hackworth), who established the Worth Engineering works of Toronto, Canada, will write the interesting life and history of John Wesley Hackworth, which ought to be given to the world, as he has a great mass of papers, letters, and much detailed information bearing up on the subject.“

- John Wesley Hackworth and his team, delivered the first Locomotive to Russia, built by his father Timothy Hackworth to Tsar Nicholas 1 via Middlesbrough docks.

- John Wesley Hackworth grew up watching and helping his father who was The Superintendent of the Stockton and Darlington Railway and went on to set up his own engineering firm in Priestgate, Darlington with a long list of patents to his name.

- But for a chapter in Robert Young‘s book on Timothy Hackworth and The Locomotive, his story is most certainly ‘seldom told’

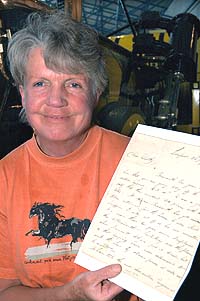

Above, Joan Hackworth Weir (nee Parsons) in her 80’s (right with hat and glasses),with Jane Hackworth Young (right), myself, Trev Teasdel and some of the Hackworth Grandsons, Kyle and Kristian Teasdel, from the Northern Echo 2005 when Joan presented to NRM the ‘Blast Pipe letters’ to Timothy Hackworth from George and Robert Stephenson, long held by the Hackworth family.

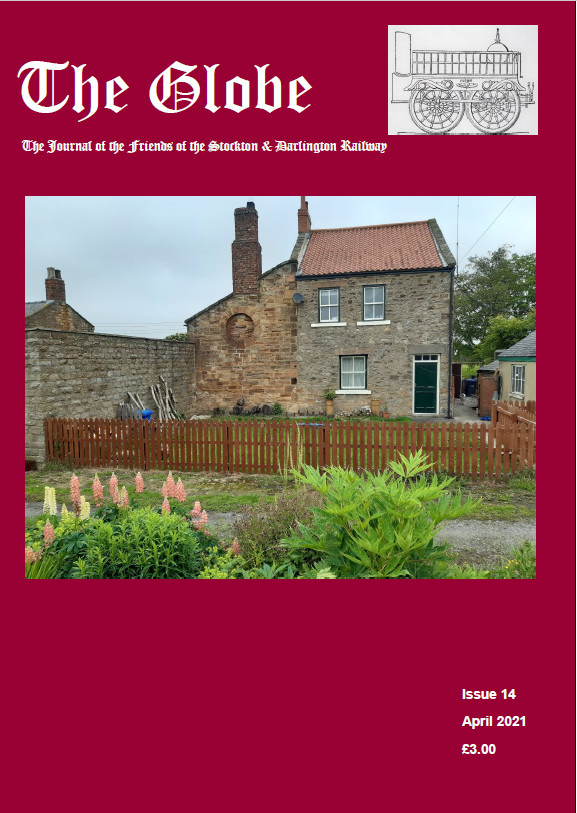

John Wesley Hackworth – Part 2 Article from The Globe

John Wesley Hackworth Part 2 Engineer / inventor – by Trevor Teasdel as published in the Globe –

Read the full magazine here on pdf https://www.sdr1825.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/The-Globe-April-2021-v2-post-circ-edits-high-res.pdf

“John Wesley Hackworth was a considerable engineer in his own right.” Ulick Loring.

“He was a man rich in inventive faculty” Robert Young

In part one, last issue, we saw how Timothy Hackworth’s son – John Wesley Hackworth and his team, successfully delivered his father’s locomotive to the Tsar of Russia at the age of 17, under perilous conditions. In part two we look at how John developed his own successful career as an engineer and inventor, building on his father’s reputation and skill and taking his work in new directions.

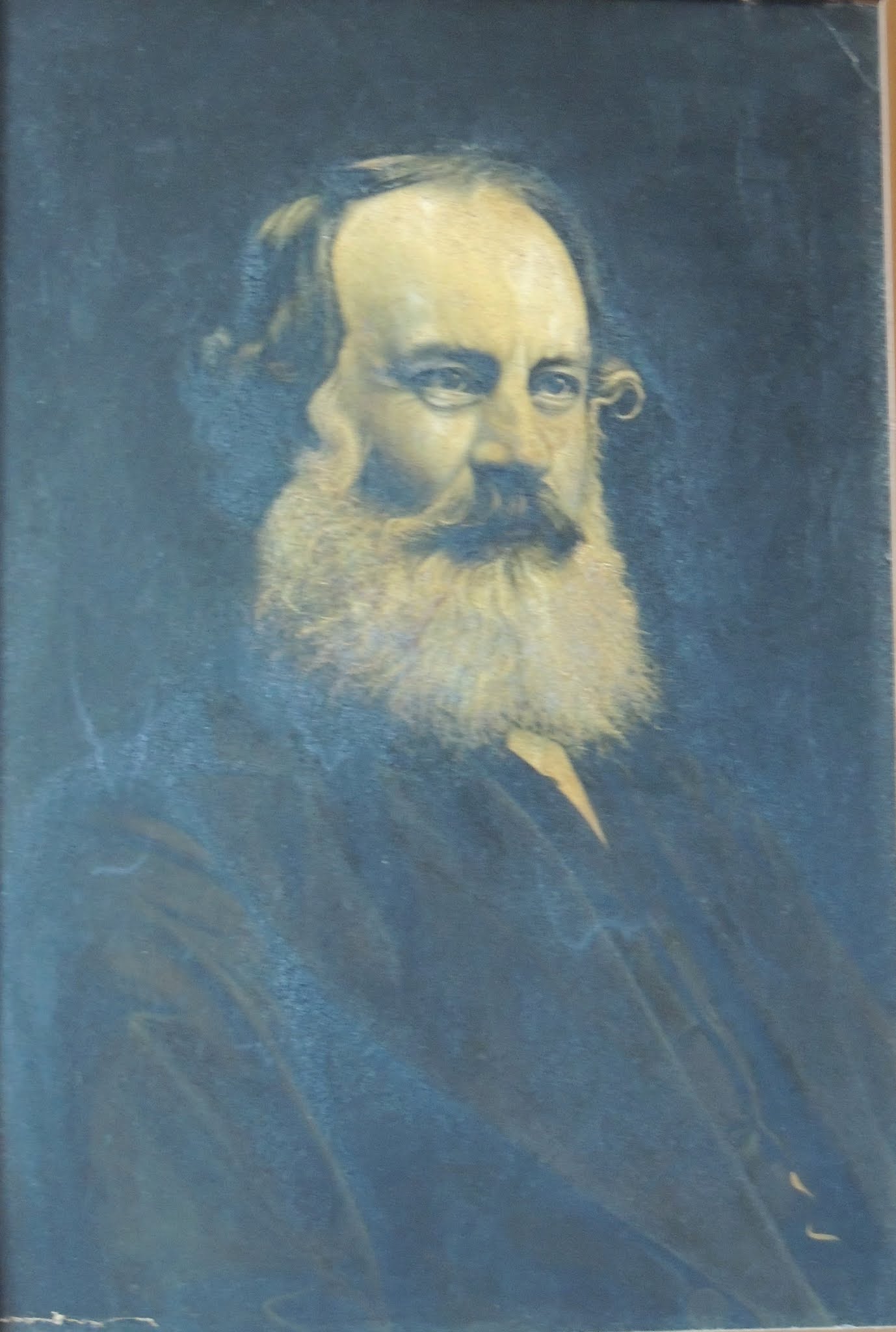

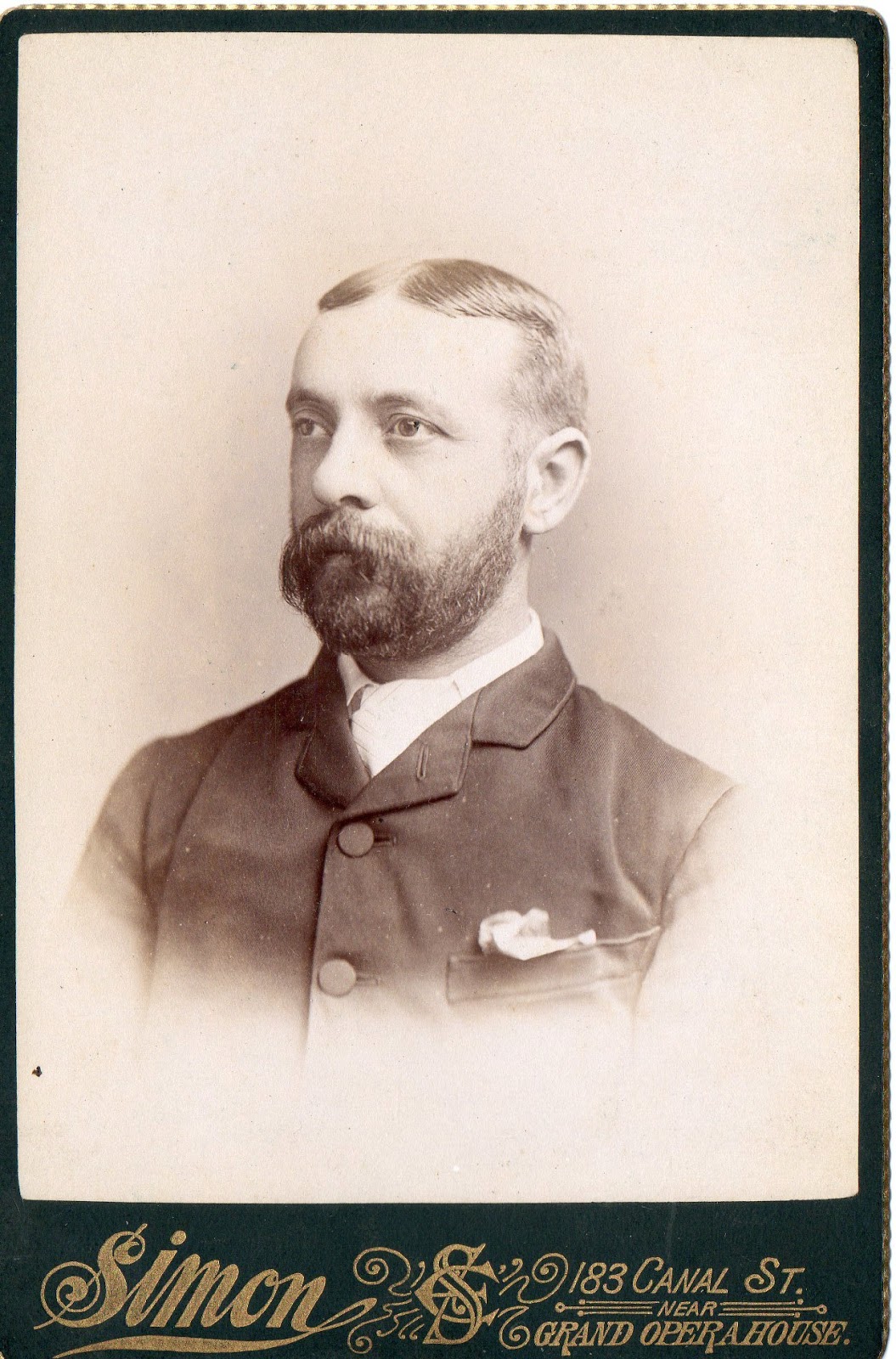

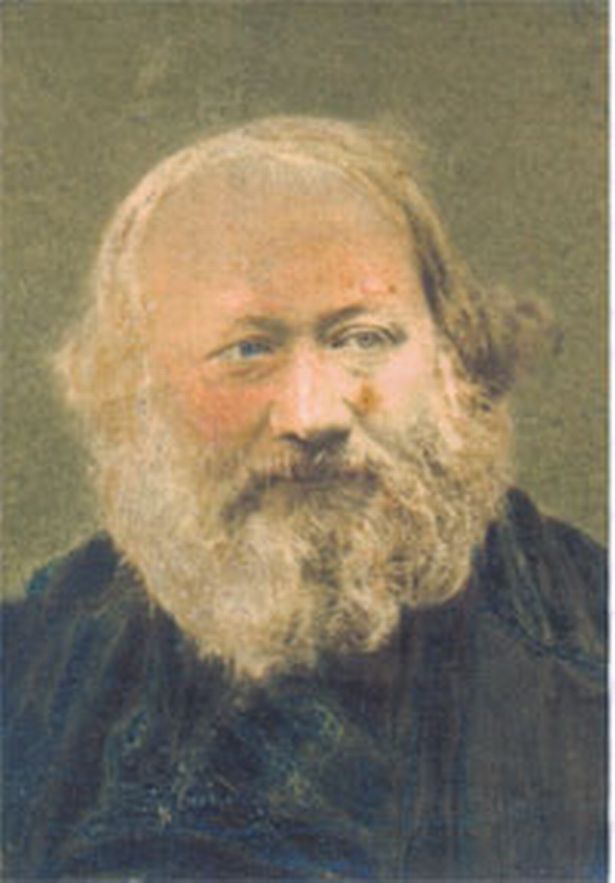

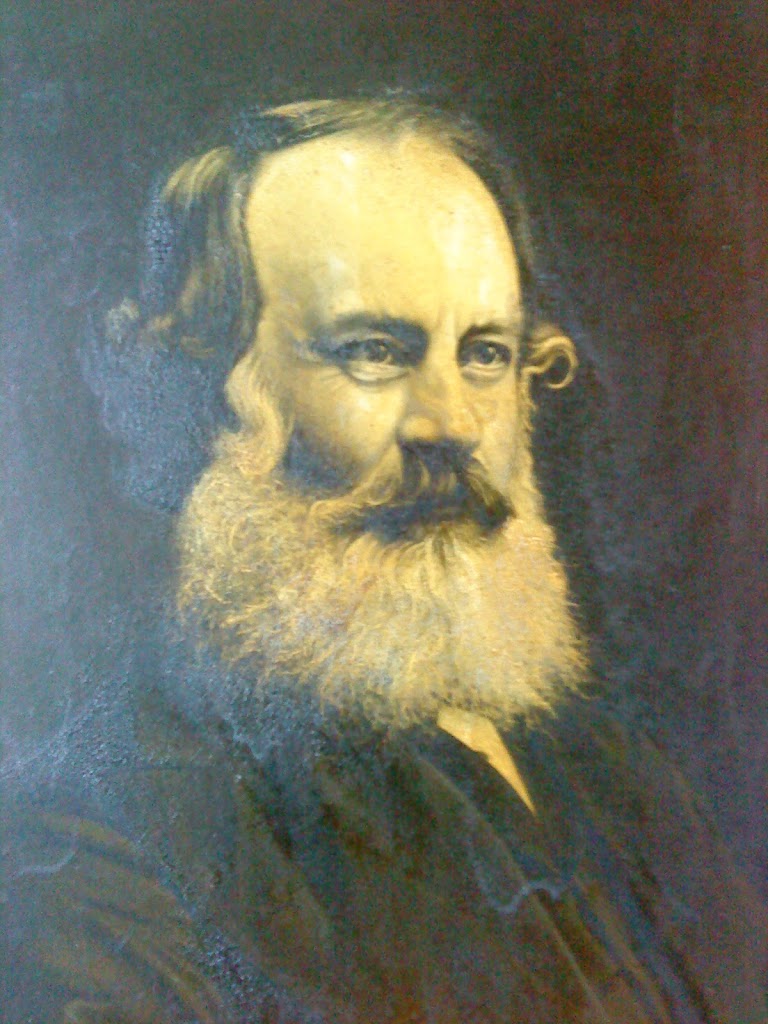

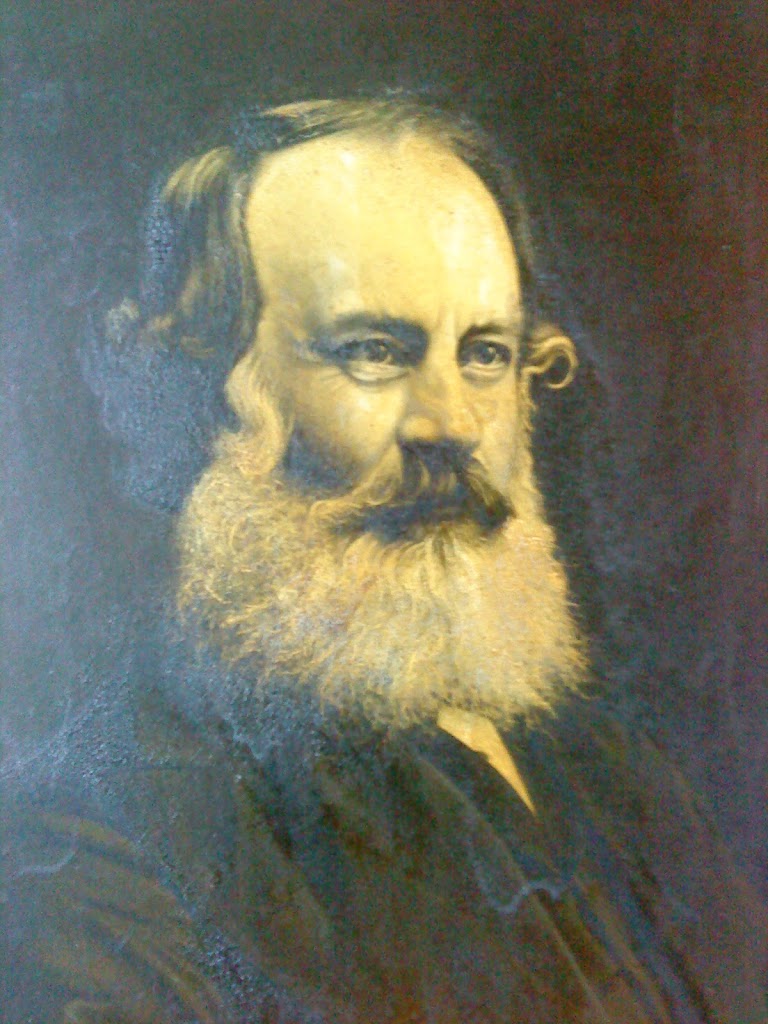

Painting of John Wesley Hackworth from the Joan Hackworth Weir Collection

Back in New Shildon

Returning to Shildon in 1837 John continued to work for the family firm at the Soho works, alongside his younger brother, also called Timothy Hackworth. Timothy Hackworth’s brother Thomas had hitherto managed the Soho works but Thomas left in 1839 to set up in business with George Fossick. Thomas had fallen into dispute with the directors of the S & D Railway and the pair set up Fossick & Hackworth, based in Stockton on Tees, where they built locomotives and carriages. (George Turner Smith’s book Thomas Hackworth is the best source on this).1

John continued to take care of routine operations at the Soho works but, things were not

always cosy! – “between 1840 to 1850, with Timothy Hackworth at the helm, the Soho Works struggled to survive. Timothy operated on the margins of profitability and the situation at the Soho Works deteriorated further when Timothy died in 1850…After Timothy’s death, there was a bitter dispute between John and the younger Timothy over whether to close the loss-making Soho works, or battle on and try and bring the company back into profit.” 2

Ulick Loring (great-great grandson of Timothy Hackworth) expands on this “The death of

Timothy Hackworth was followed by the sale of the Soho works though attempts were made to keep them going. It turned out to be a sad and unsatisfactory process for the family. It was not helped by the death of Hackworth’s widow, Jane, two years after him, and then followed by the death in 1856, of his second son, also Timothy, who was keen to keep the works in the family.” 3

On a more personal level, love was certainly on John Wesley Hackworth’s mind when he

returned to England in 1837 – Ulick continues –

“John proposed to a young woman by the name of Jane Dunton from Newburn, near

Newcastle who turned him down. Her letter of rejection of 1st July 1838 still exists (in the

Hackworth family Archives NRM York). It was said in the family that after this experience he vowed to marry the first girl he met. When he did marry it was to a girl called Annie Turner.” 4

By 1851, the Census shows –

| The Great Exhibition |

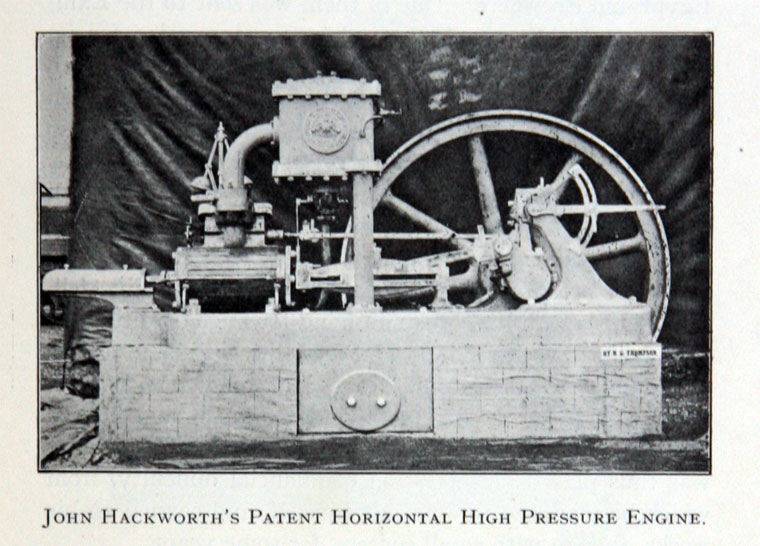

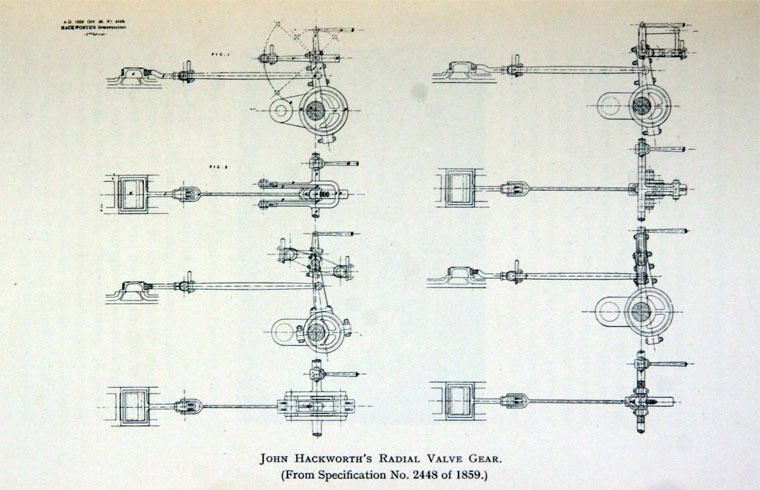

John Wesley Hackworth exhibited his Horizontal High Pressure Steam Engine, which

combined the ‘pass over’ slide valve originally patented in 1849 and applied in the Sans

Pareil No2, the patent Tubular Heating Cistern, the ‘Dynamic’ Valve Gear, and some original features in construction which included an improved wrought iron crosshead in one piece.

Robert Young notes “The piston rod was carried through the cylinder into a box to prevent

elliptical wear and undue friction. All the journals, joints and motions had double the usual

amount of rubbing surface and special regard was paid to strength and simplicity in details,

oil syphons were provided, and the cylinder was lagged with mahogany. The foundation plate was of the ‘box girder’ type and the whole appearance was neat and every working part easily accessible.” 14

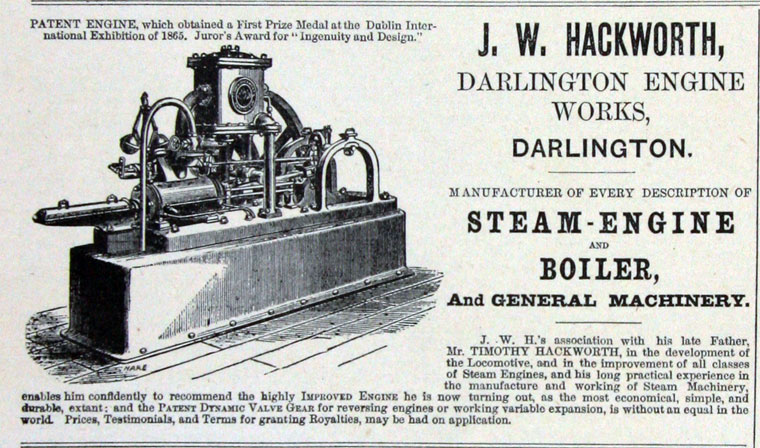

In Egypt, at this period, there was a great trade opening. The civil war in the United States

had ruined the cotton industry, and in looking for other suitable countries for cotton growing

the prospects of Egypt were specially promising. The Khedive had visited the exhibition of

1862 and John Hackworth’s engine was brought to his notice. With an economy in fuel of 25 to 30% over other engines, simplicity in construction, and economy of space, the engine achieved a high reputation, and many were manufactured and sent both to Egypt and elsewhere. One of them was sent to the exhibition at Dublin in 1865 and received a prize for its excellence.

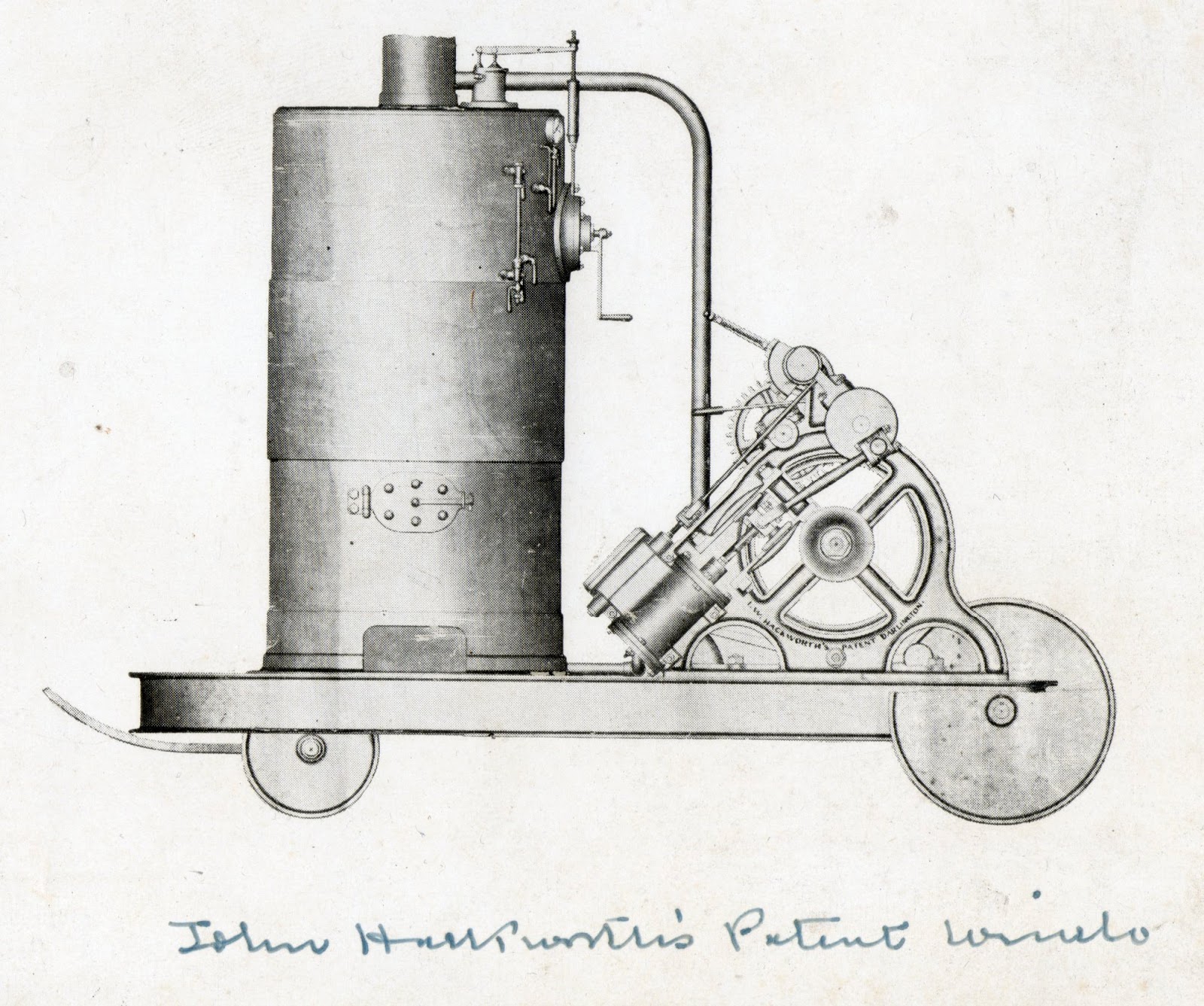

“Following up this opening, John Wesley Hackworth began manufacturing cotton machinery for Egypt, which was carried out with great success for some time. He also designed a steam winch, which was largely used on steamers. Out of the proceeds he built himself a new works at Bank Top, Darlington. These he specially designed and they were commodious and complete in every respect.” 15

The Fall of the Khedive

When the Khedive fell, John had orders in hand for huge quantities of machinery of various

kinds, and the fall came just at a time of completing. Not only was a great amount of it left on his hands, but for much that he had already dispatched he never received any payment. He was thus placed in a position of financial difficulty and it was feared he would have to go into the workhouse but through the efforts of his family, and particularly his sister Prudence, he escaped that fate. He carried on his works, though with small success for some years. Like his father, he also built winding engines for collieries, one of which at Shildon Colliery, was erected in 1870 and was still there in the 1920’s. The engineering works in Darlington were given up about 1871.

In 1872 John Wesley Hackworth visited Canada and the United States, partly to recuperate his health and partly with a view to introducing his Variable Expansion Valve Motion. He brought it before the United States naval authority but without success. However, when he left England some 50 steamers had been fitted with the gear in addition to a number of stationary engines. In America, a locomotive on the Hudson River Railway was provided with it experimentally in 1873.

However, he was a man rich in inventive faculty, and obtained a patent in 1874 while in the

United States, for Metallic Packing, which he described as an invention to secure internal and external tightness, that is freedom of leakage in the moving parts of machinery under vacuum or pressure, in dealing with fluids such as steam, gas, air, oil or water.

Consultant Engineer 1875

In 1875 he returned to England as a consultant engineer in Darlington, later moving to

Sunderland, and eventually to London. Robert Young says “He devised an arrangement for a better ventilation of mines and spent a considerable sum in preliminary experiments, but the cost of installing it prevented its adoption. Mine ventilation was no new hobby with him. It had been the subject of deep interest and concern to Timothy Hackworth, and the son had given much time and study to a question which affected the lives of the mining population among whom he had been brought up.” 16

John Wesley Hackworth – Part 1 (Inventor, Engineer, Advocate) Article by Trev Teasdel

I wrote a three part article on John Wesley Hackworth for the Globe – Journal of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. This is Part 1.

About the Globe – See here https://www.sdr1825.org.uk/about-us/

Read the whole of this issue on pdf Here https://www.sdr1825.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/13-The-Globe-Dec-2020.pdf

|

John Wesley Hackworth –

(Inventor, Engineer, Advocate) Part 1

By Trev Teasdel

|

John Wesley Hackworth 1820–1891cut a controversial figure in locomotive history and yet those who know of him, probably only know that he was Timothy Hackworth’s son, that he delivered to Russia its first successful steam locomotive and was caught up in controversy over the defence of his father’s reputation. What follows is a portrayal of his life and work and along the way I hope to highlight some areas that need further research. My lads are descendants of John Wesley Hackworth on their mother’s side. Their maternal grandmother was Joan Hackworth Weir (nee Parsons). Joan left a case of Hackworth material in her loft – letters, cuttings and much more, all of which I have put online. 1

1 Because there was nothing much on him on the internet,

2 I am currently working on a website for John Wesley Hackworth. 2

John was born in Walbottle in 1820 and lived there with his parents Timothy Hackworth and Jane Hackworth, nee Golightly, until he was five. Timothy was Foreman of the Smith as he had been at Christopher Blackett’s Wylam Colliery. In 1824 he was prevailed upon by George Stephenson to go to the Forth Street Works at Newcastle as ‘a borrowed man’ to oversee, amongst other things the building of Active as originally named but later became known as Locomotion No 1. By the time John was five, Timothy had finally accepted a position as ‘Superintendent Engineer’ of the Stockton & Darlington Railway and the family moved first to Darlington and then in 1826 to a house in the first terrace built in New Shildon.

It was here that John’s education began. Robert Young says “He was a clever boy but no

student of books. While other children were spinning tops, he was spragging the wheels of

coal waggons as they reach the bottom of the incline or riding on the locomotives. He went

with the Royal George on its trip and knew as much about it as most of the men and a good deal more than some of them. He thus began his early training as an engineer and never dreamt of any other career. It was part and parcel of his existence and he was a born mechanic.” 3

John occupied a unique place in history, growing up and working/learning with his father,

Timothy Hackworth, the first Superintendent of the S & D Railway and creator of the Royal

George. John would later say of those days “I saw the Stockton and Darlington Railway

opened, was brought up upon it, knew every horse, every locomotive driver, and fireman,

every director, nearly all the shareholders, and every noteworthy incident that occurred

thereon for the first 20 years; and if any living man knows anything of its history, and working, I am the man!” 4

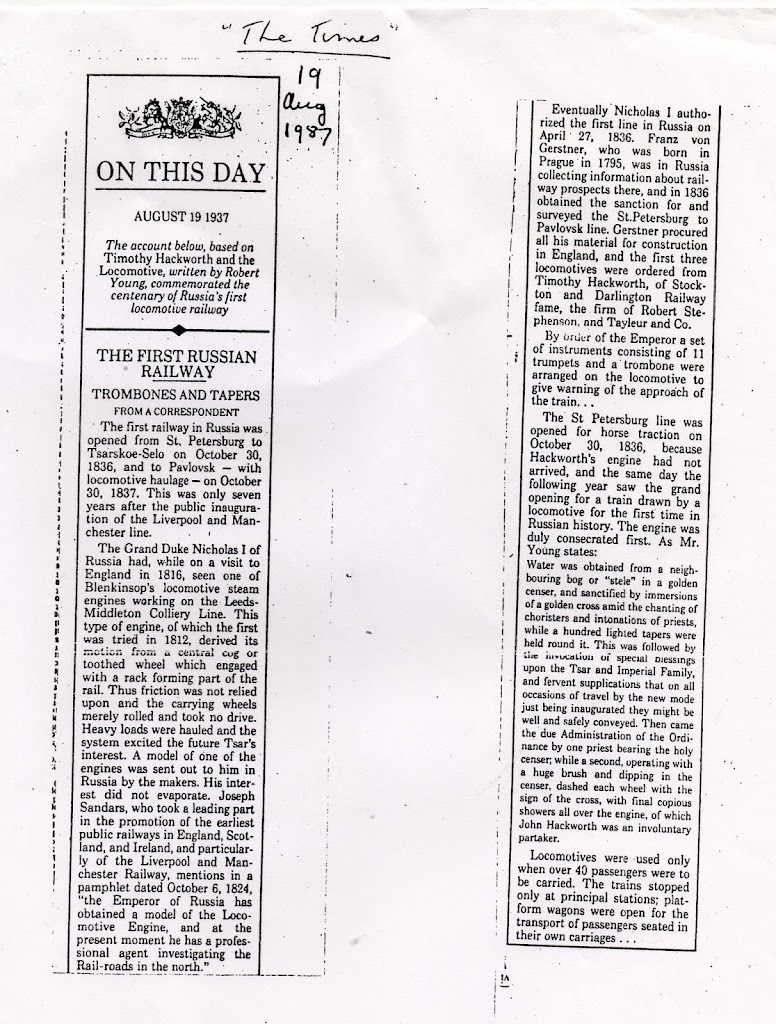

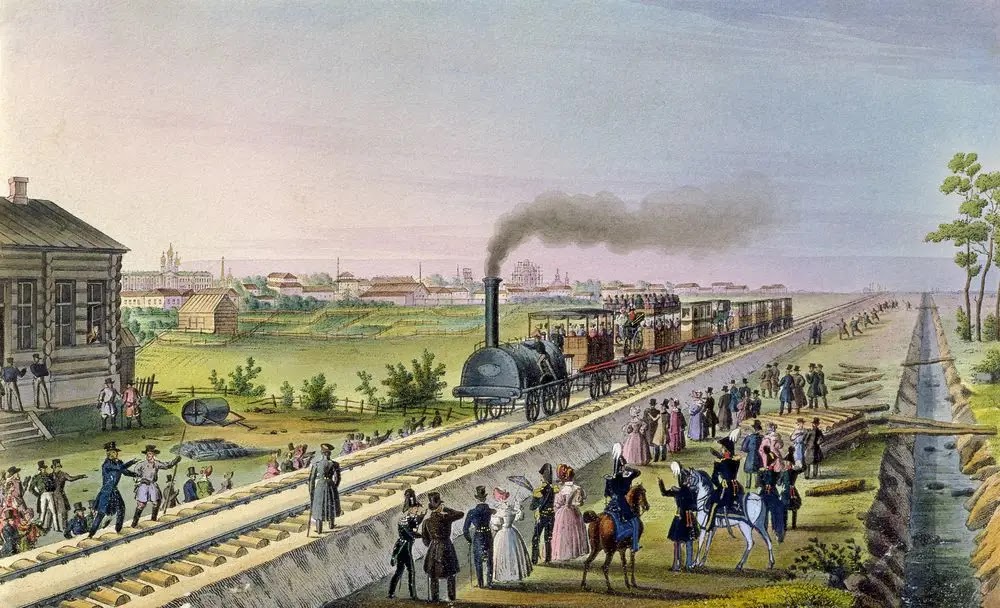

The First Russian Locomotive

In a paper from 1956, David Burke wrote that in 1836 “A 16-year old English boy (John

Wesley Hackworth) gave Russia her first railway locomotive. He (and his team) faced

blizzards, wolves, and misfortune, and at the end of his journey, crowds cheered him, priests blessed him, and he received the Tsar’s congratulations” 5

Ulick Loring (the great-great grandson of Timothy Hackworth) comments “for a young man

reared in the austerity of nonconformist north-east England, to be exposed to Imperial

Russian life must have been a heady experience. It is difficult nowadays to imagine the

contrast between English and Slavic religion and culture and how it could affect visitors from Western Europe. His locomotive was the first among several ordered from Western Europe, to arrive at St. Petersburg. This was on 3rd October 1836 (Russian Calendar).” 6

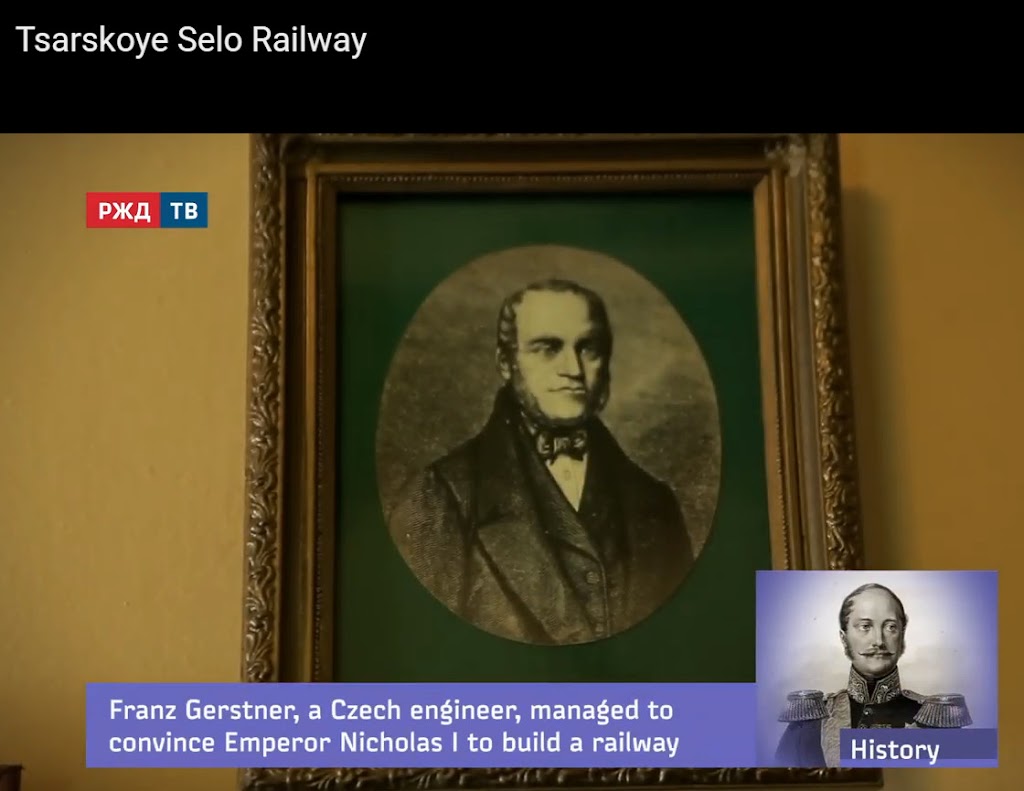

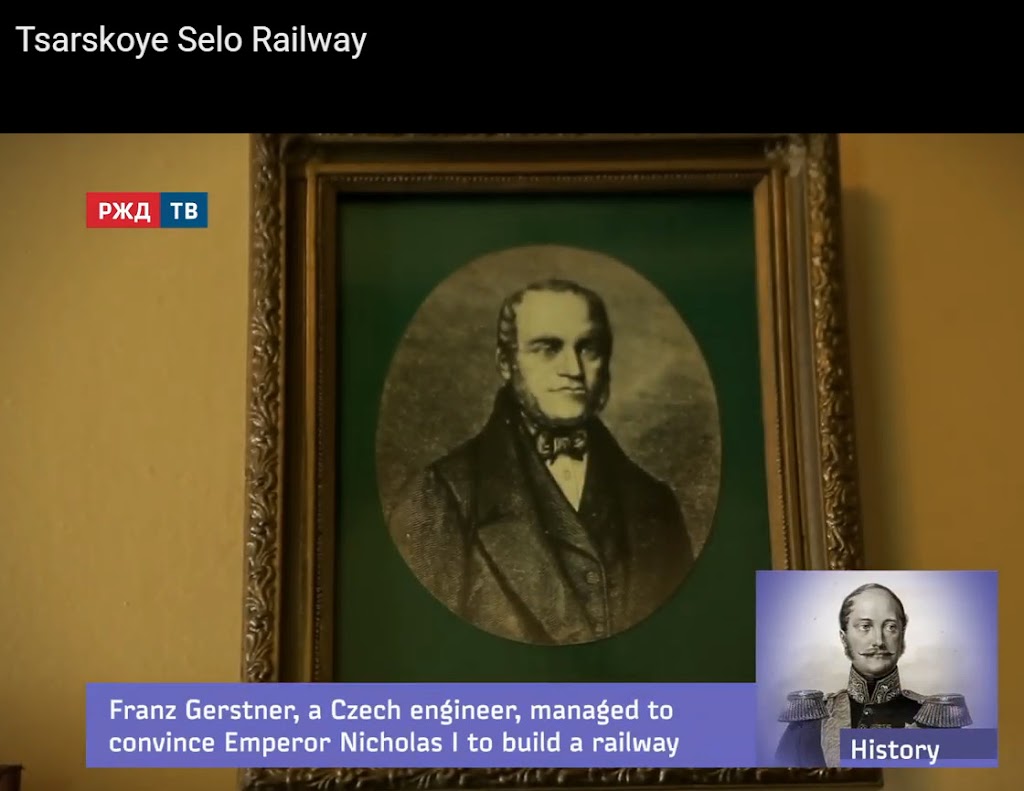

The need for a more efficient transport system in Russia had become urgent and

Czechoslovakian engineer, Franz von Gerstner, was appointed to oversee the project.

George Turner Smith tells us

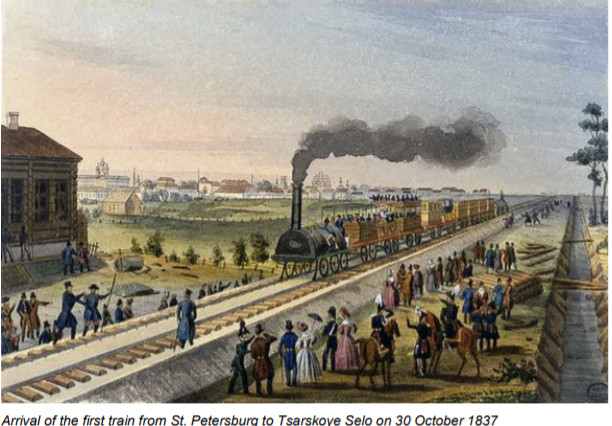

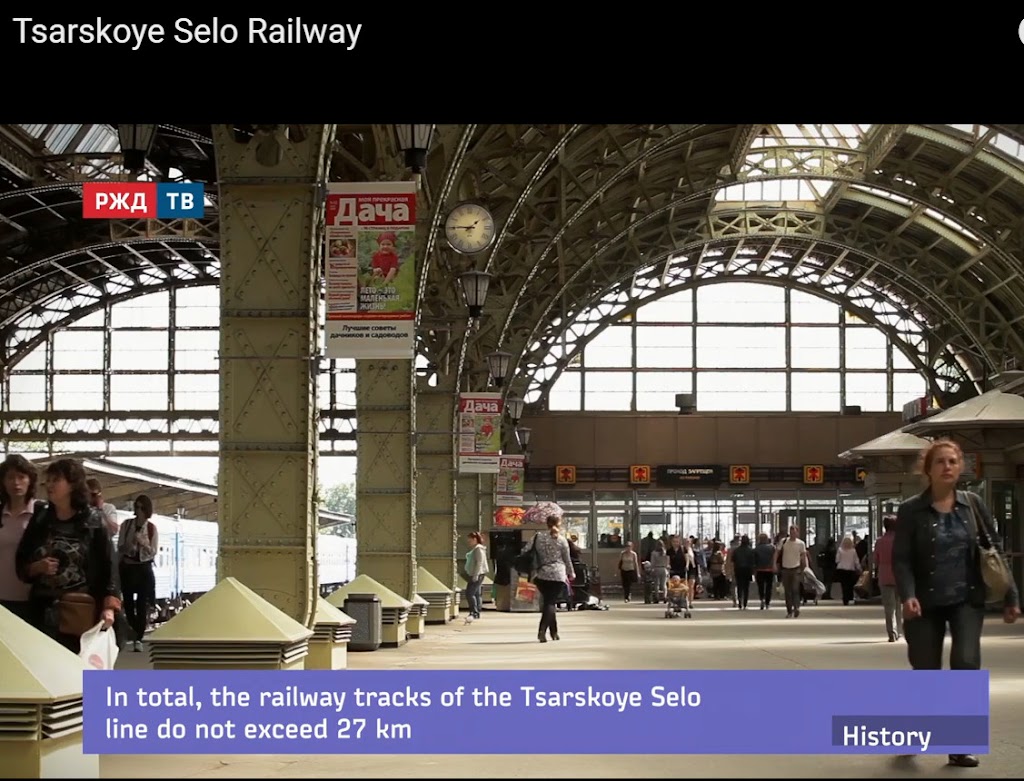

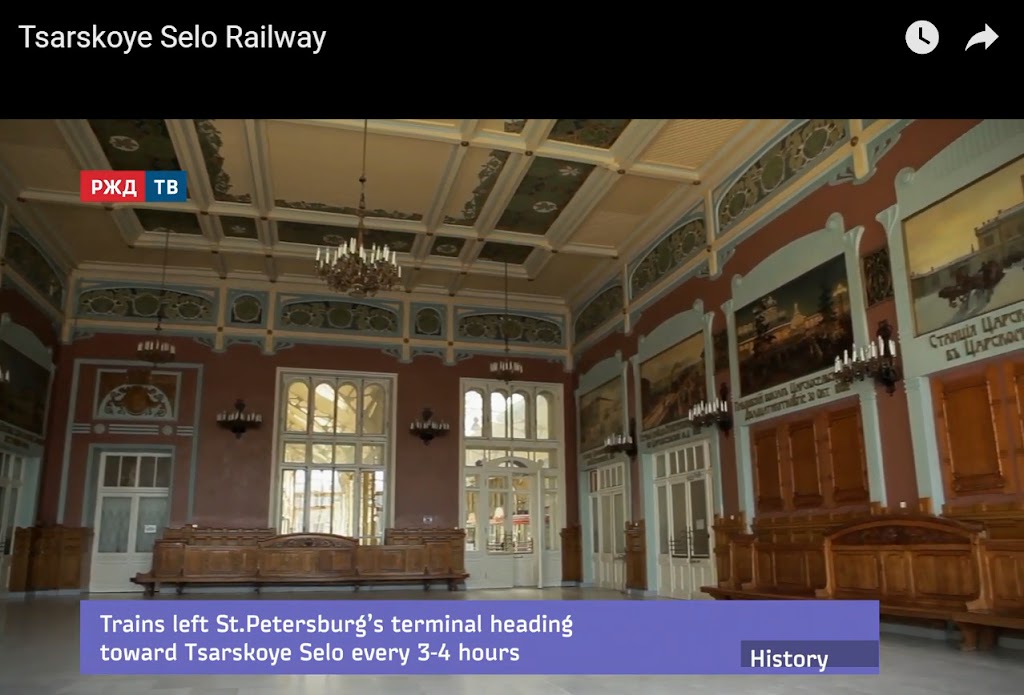

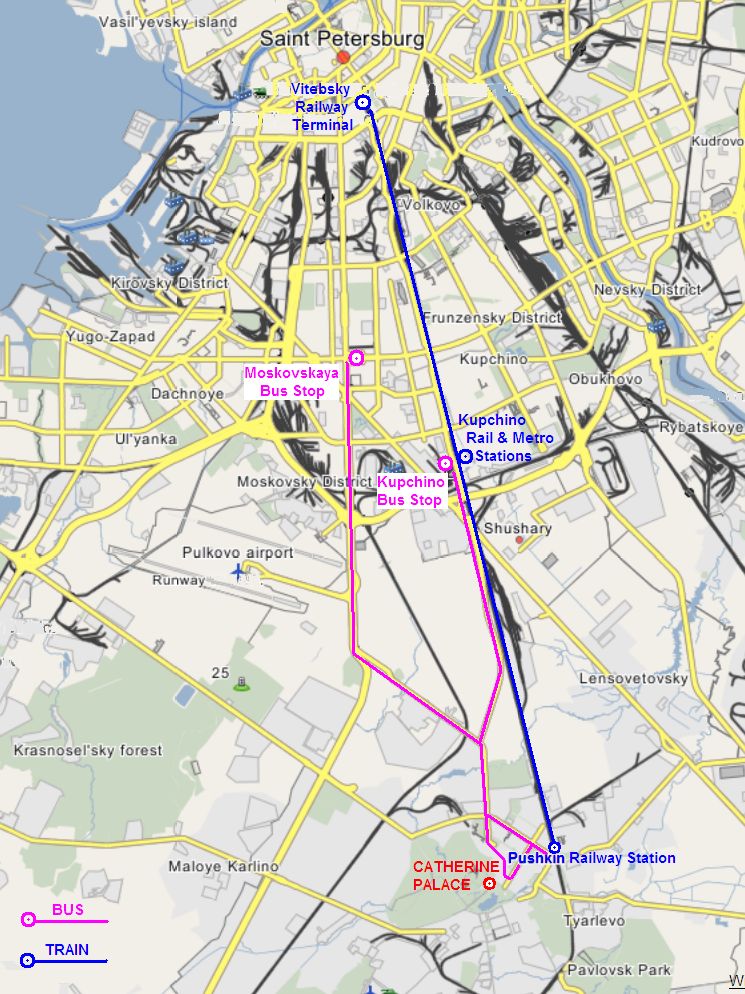

“The first 15 miles of single track was laid down between St Petersburg and Tsarskoe-Selo

where the Tsar had his Summer Palaces. Seven locomotives would need to be purchased

from abroad, six from England and one from Belgium. The English contingent comprised four from Robert Stephenson’s works in Newcastle and two from the Vulcan Foundry at Newton-Le-Willows. However, because of outstanding commitments, Stephenson found that he could only supply two from Forth Street and Soho works was contracted to provide the rest.” 7

The duty of introducing the locomotive to Russia devolved upon Timothy Hackworth’s eldest son, John. Such a journey at that time was a perilous proposition and Timothy’s decision to send his son couldn’t have been taken lightly! It may have been because both Timothy and Thomas were under considerable pressure and Thomas had just got married to a French woman, Adele Celestine Hennon, but as Robert Young says John Wesley Hackworth was ‘a well set up youth, nearly as tall as his father, and a keen and clever engineer, absorbed in his profession and in appearance, much older than his years.’

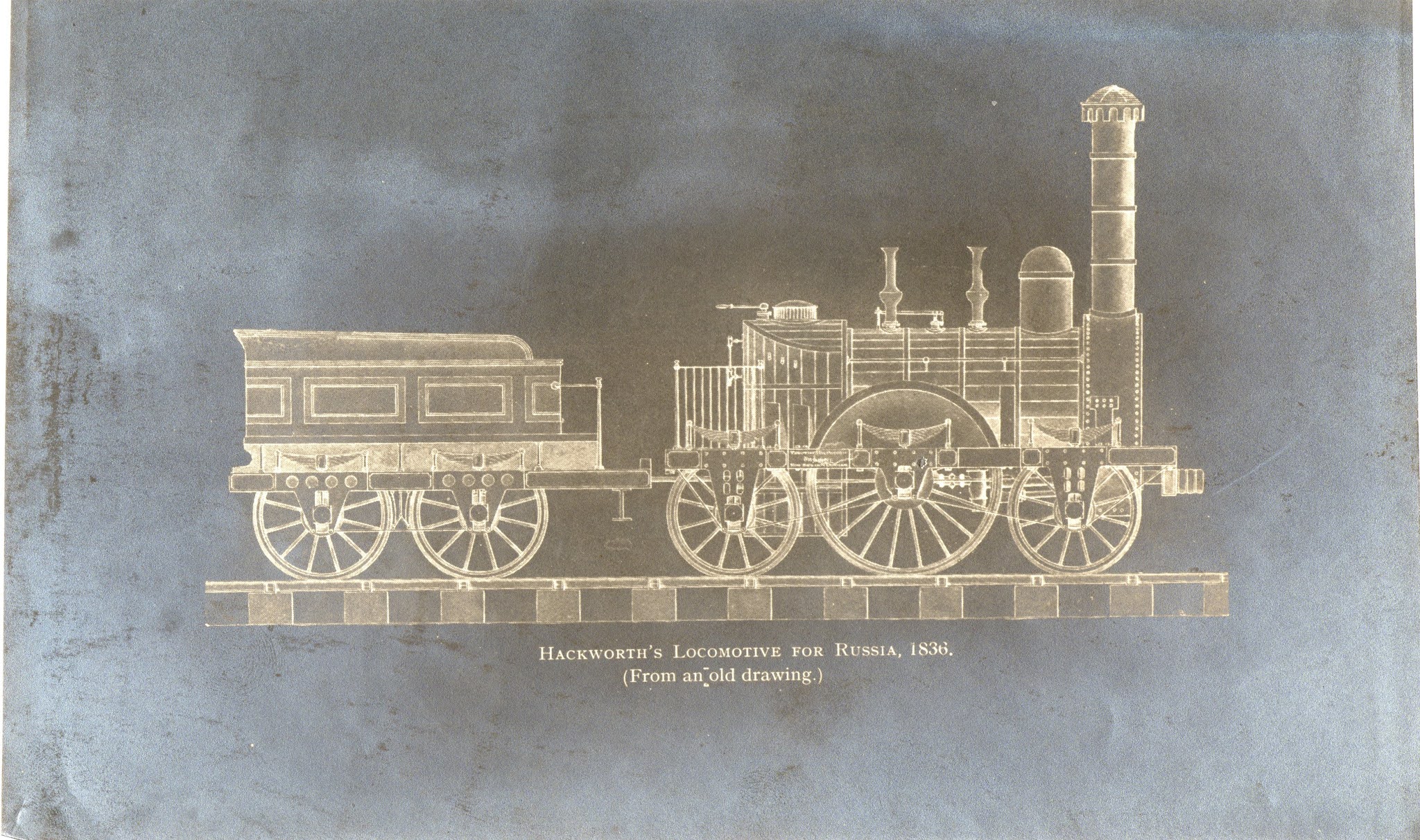

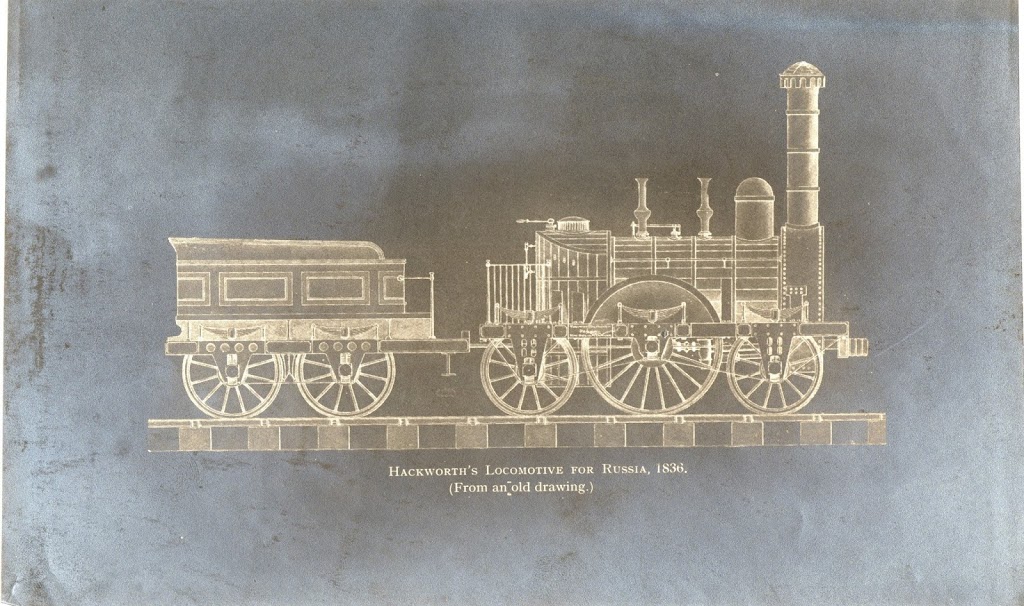

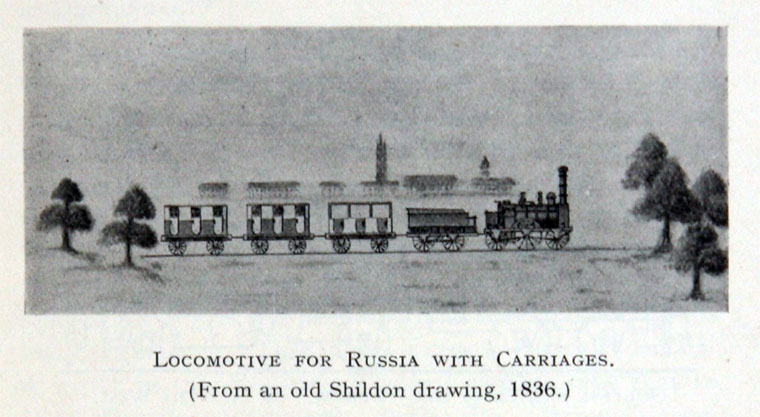

Two engines were outsourced to the Hackworth’s Soho works, New Shildon but only one was built, and this was the first to be delivered to Tsar Nicholas 1. George Turner Smith says, “In effect, the engine was a typical Stephenson 2-2-2 ‘Patentee…The engine was crated up and transported on a modified flat-bed wagon, along the S&D rails to Port Darlington in Middlesbrough…The locomotive was loaded on to the brig – Barbara.” 8

On the 17th September 1836, The Durham Advertiser reported –

“On Thursday, 15th September, a large and powerful locomotive engine, built by Timothy

Hackworth of New Shildon for the Emperor of Russia was shipped on board the ‘Barbara’ at Middlesbro’. This engine is constructed on an improved principle and finished in the best

manner. She has been tried on the premises and propelled at the rate of 72 miles per hour.

Petersburg, have cost the Emperor upwards of £2,000 each. Who, a few years ago, would

have dreamed of the exportation of machinery from the River Tees? This engine is for

travelling on the railroad from St. Petersburg to Pavlovsky where stands one of the country

palaces of his Imperial Majesty.” 9

The locomotive arrived at Port Darlington, Middlesbrough along with Hackworth’s team of

engineers. It is assumed the Barbara would be a brig but nothing much is known about it. For any Middlesbrough historians wanting to do some research on the ship, the records from Customs House, Middlesbrough, are now in Teesside archives.

Hackworth’s locomotive for Russia 1836. Image from the Joan Hackworth Weir Collection

It was previously surmised that John Wesley Hackworth travelled with the team from Shildon to Middlesbrough but in searching the Hackworth archive we discover that John Wesley Hackworth was travelling to London with his father, on business and intended to board a ship in London to catch up with the team in Hamburg. He missed his initial connection but managed to board a later ship and reunite with the team.

A description of the Letter from Timothy Hackworth (Guild Hall Coffee House) to Jane

Hackworth 22nd September 1836 reads “we were to [sic] late in reaching London the vessel had been gone 15 minutes. One Mr Kitching from Lancashire has to go to St Petersburg to fix two weighing machines, he together with his niece and son John all go on board on Friday night and sail for Hamburg on Saturday morning and I think of coming home by Majestic…….’ 10

At that time, the Baltic was frozen over so the team had to travel from Hamburg through 500 miles of frozen desolate country with wooden sledges, before the spires of St. Petersburg came into view. David Burke, who had sight of the lost John Wesley Hackworth diary of the trip, quoted it saying “Blizzards nearly blinded them, wolves attacked them and only by whipping the horse teams into a frenzy did young Hackworth and his team escape the snapping jaws.” And Robert Young adds that “the weather was so severe that the spirit bottles broke with the frost.”

Clearly in 1836, delivering a locomotive was no easy task but it was by no means the end of their troubles. While assembling the locomotive in St. Petersburg, a cylinder cracked and with no workshops in the city capable of fixing it, Hackworth’s foreman George Thompson heroically took the cylinder from St. Petersburg to Moscow, a distance of some 600 miles, to the armoury where they made a pattern for the cylinder, got it cast, bored out and fitted, returned to St. Petersburg, and fixed it in the engine.

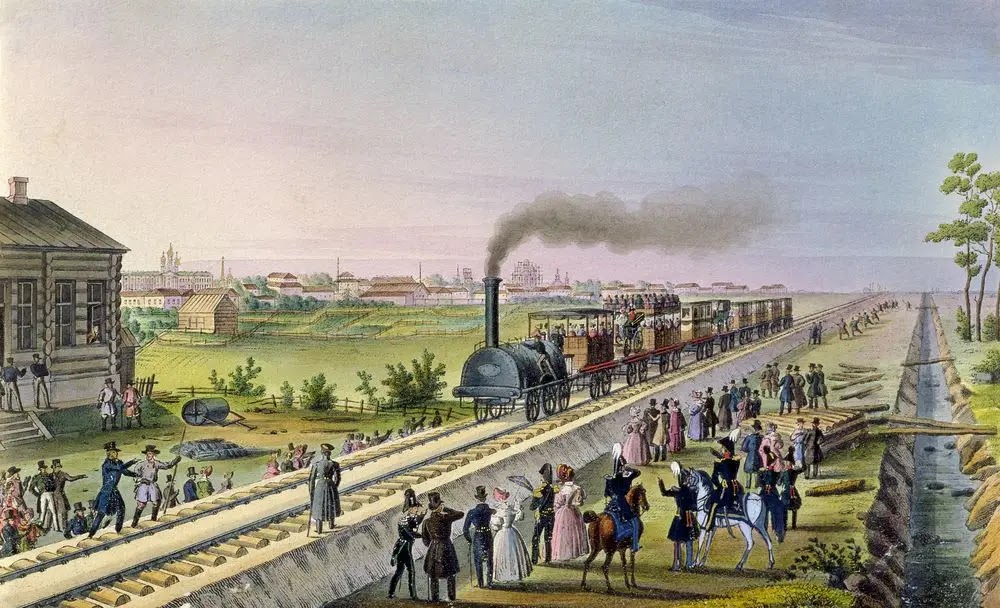

The Launch of the Russian Locomotive

David Burke12 tells us “In November 1836 bells pealed in St. Petersburg, guns boomed, and the line was opened with great crowds cheering, gaping Russians who had never seen an ‘Iron horse’ before’. John Wesley Hackworth drove his puffing, hissing charge into Tsarskoye-selo where the Tsar Nicholas 1 and his family and generals waited to see him arrive. Not that the opening of the first railway in once Holy Russia was as simple as that – a score of orthodox priests descended on the engine with crosses, candles, censers, and holy water to perform the blessing ceremony”. “They splashed me in the process” Hackworth wrote in his diary.“13

Robert Young elaborates “This was the baptismal ceremony of consecration according to the rites of the Greek Church done in the presence of an assembled crowd. Water was obtained from a neighbouring bog or “stele” in a golden censer and sanctified by immersions of a golden cross amid chanting of choristers and intonations of priests, while a hundred lighted tapers were held round it. This was followed by the invocation of special blessings upon the Tsar and Imperial Family, and fervent supplications that on all occasions of travel by the new mode, just being inaugurated, they might be well and safely conveyed. Then came the due Administration of the Ordinance by one priest bearing the holy censer; while a second, operating with a huge brush and dipping in the censer, dashed each wheel with the sign of the cross, with final copious showers all over the engine, of which John Hackworth was an involuntary partaker.” 14

Hackworth related in his diary how he was introduced to the Tsar who told him of a visit to

England in 1816, when he had witnessed the running of Blenkinsop’s engine on the colliery line from Middleton to Leeds. The Tsar added some complimentary remarks regarding the new locomotive, saying he ‘could not have conceived it possible so radical a change could have been effected within the last 20 years. The Tsar also told him that “It was an occasion of great progress and other ‘Iron horses’ would surely spread across the nation.”

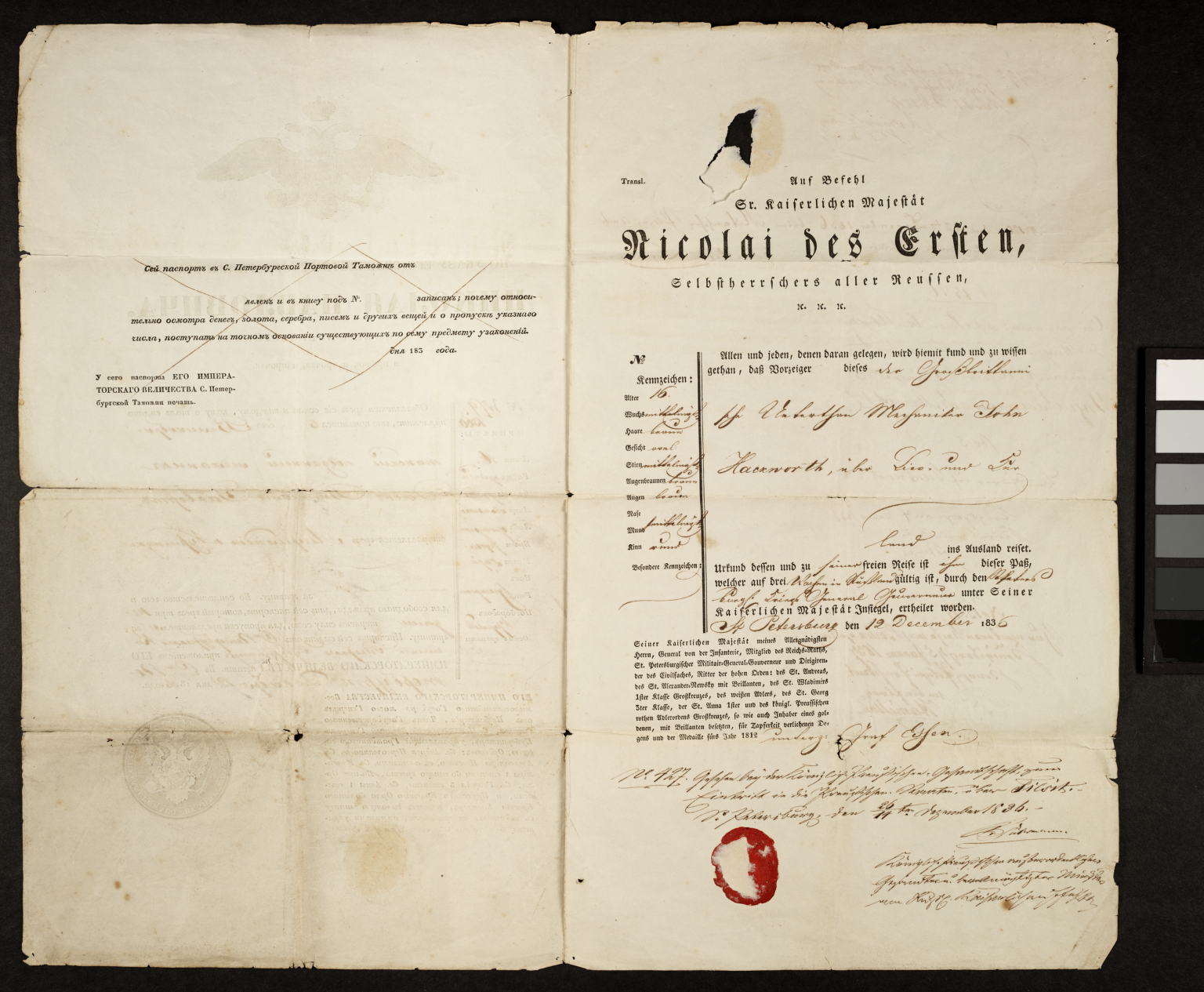

John Wesley Hackworth’s Passport

On the 12th December 1836, John was granted a Russian passport for the homeward

journey, by the Tsar himself. The name on the passport read John William Hackworth,

because, as George Turner Smith remarks “his name was considered unsuitable for a visitor to Mother Russia.” Timothy Hackworth was a Methodist and named his son after

| John Wesley but for the passport they changed Wesley to William so as not offend the Russian Orthodox church. The passport was kept by John Wesley Hackworth’s descendants until 2005 when Joan Hackworth Weir donated it to the Hackworth Archives at NRM, York. The passport reads: “By Edict of his Majesty, the Sovereign Emperor. Nikolai Pavlovitch, Autocrat of all the Timothy and the family were surprised and alarmed when John returned with a full Russian In part two, next time, we will look at his life as an inventor, manufacturer, consultant |

Notes |

THE BATTLE OF THE BLAST PIPE from the Globe Part 3

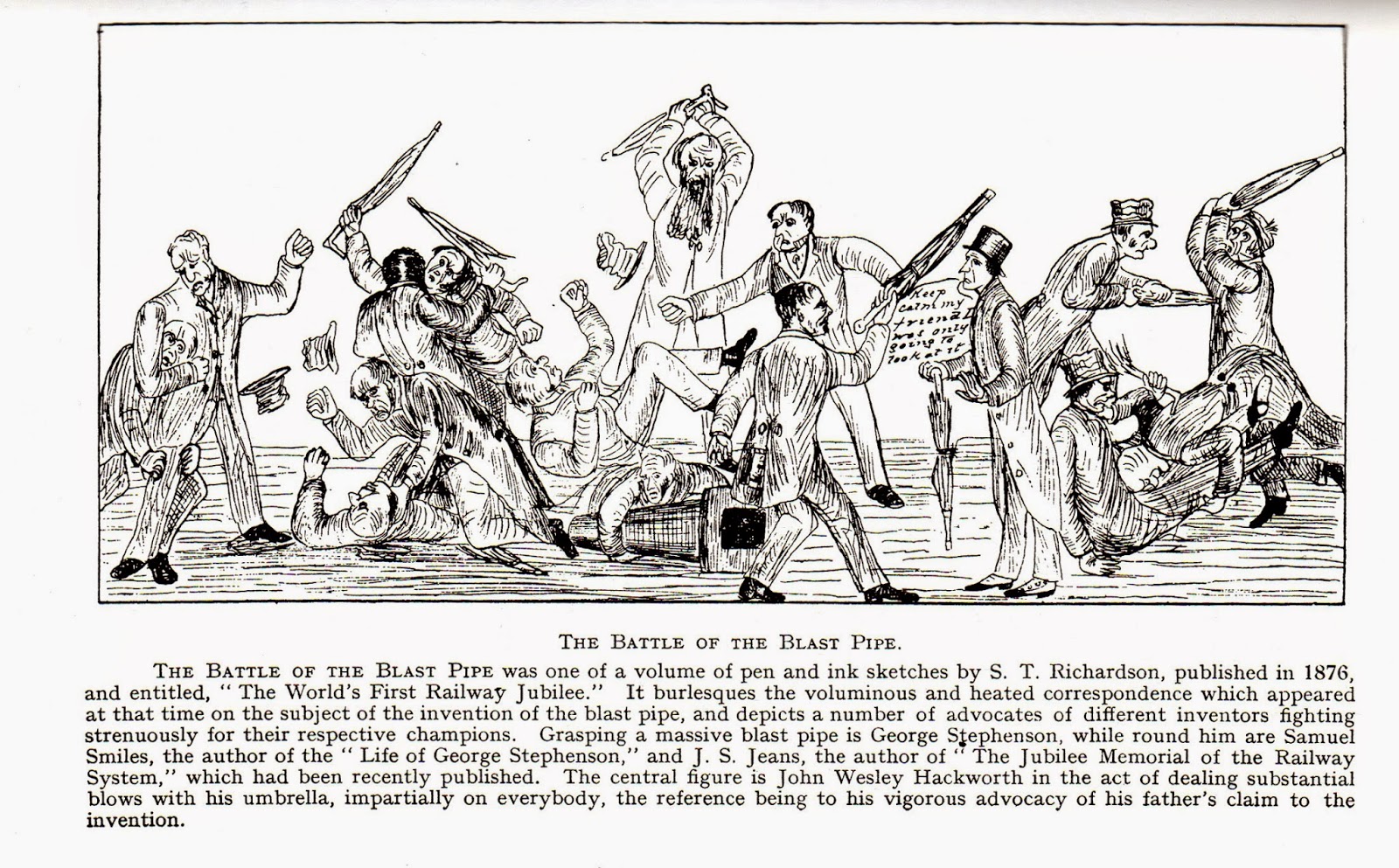

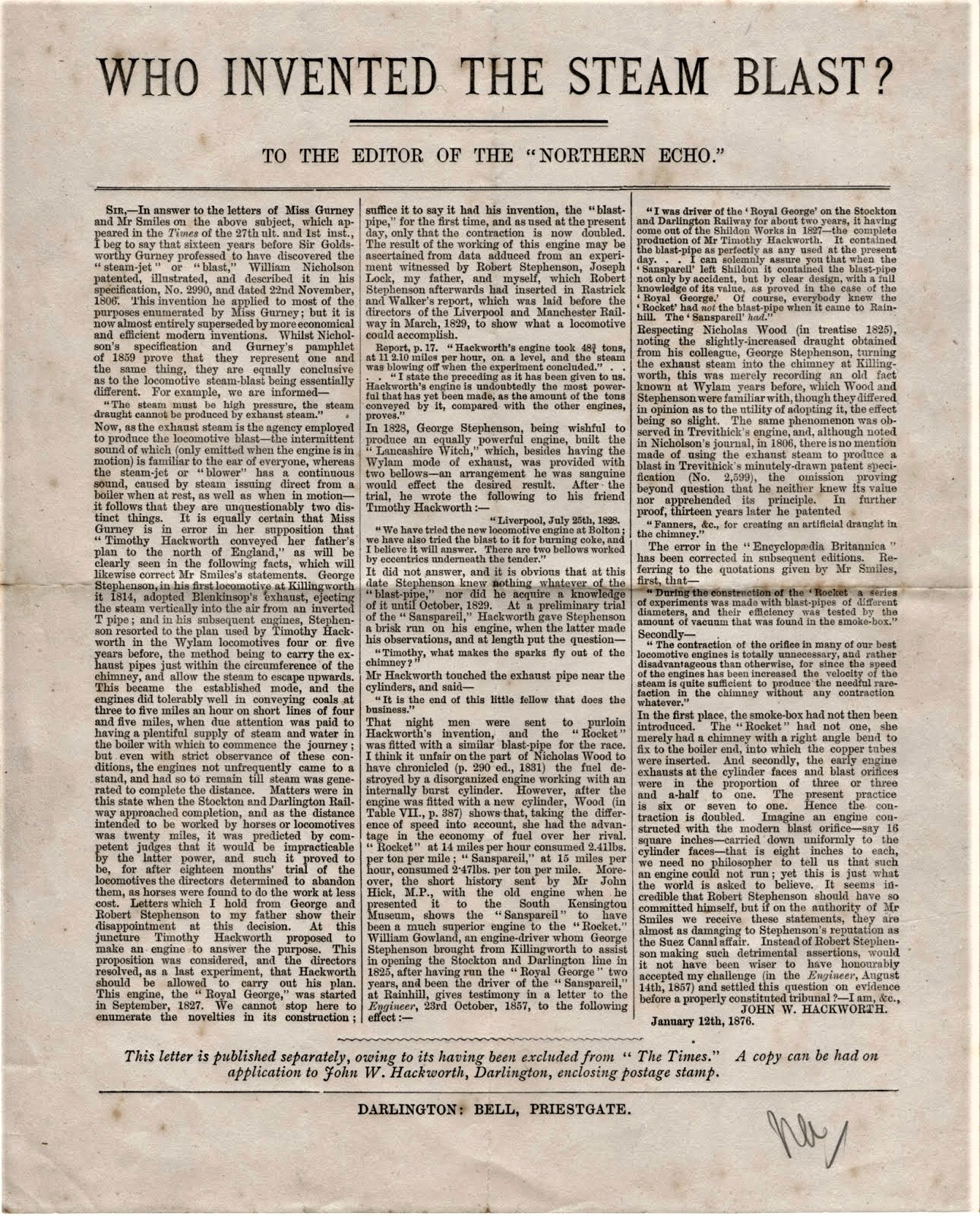

In 1876 S.T. Richardson published a pen and ink sketch entitled The Battle of the Blast Pipe in a book of sketches called “The World’s First Railway Jubilee” which ‘burlesques the voluminous and heated correspondence’ that appeared in the press at that time on the subject of the invention of the ‘blast pipe’ with John Wesley Hackworth lampooned in the centre dealing ‘substantial blows impartially to everyone with his umbrella, the reference being to his vigorous advocacy of his father, Timothy Hackworth’s claim to the invention’. The sketch depicts other fighting advocates including George Stephenson, Samuel Smiles and J.S. Jeans, author of The Jubilee Memorial of the Railway System.

John Wesley Hackworth – Meet the Parents!

|

| John Wesley Hackworth (from a painting in the Joan Hackworth-Weir Collection.) |

Jane Hackworth (née Golightly) (His mother)

|

| Jane Hackworth (née Golightly), Timothy Hackworth’s wife (from the Joan Hackworth-Weir Collection.) |

Timothy Hackworth married Jane Golightly in 1813 at the age of 27 at Ovingham Parish Church where he had been baptised. Robert young tells us Jane “was a tall, handsome and well educated woman of roughly the same age.” She entered into her husband’s work, social, religious and professional life with great heartiness and sympathy. “Numerous family letters have been preserved which bear evidence of the knowledge and interest mutually held in Hackworth’s business and doings, and of the affection and complete understanding between the two..“ Robert Young Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive p75

Later in the book Robert tells us ” She was a women of great individuality, competent, energetic and an admirable housewife and…. had, in her younger days been a fine horsewoman. Like her husband, she had been attracted to Methodism, and on this account had been compelled to leave her home and live with a relative, her parents being rigorous members of the established church.”

Note – the two photos below are of Ovingham Church where Timothy and Jane were married)

On her death, a friend of the family – John Cleminson wrote ” I have always looked up to her as one of the most Holy and devoted mothers of Israel. Her zeal for God was always manifested in her regular attendance on all the means of grace. At a time when the prayer meeting was kept up at 5 O’clock every morning in the week, she was generally there with the first and when she exercised in prayer, the power of God was always manifest. the whole of her life was that of the Holy devoted Christian. When the Wesleyan Chapel in New Shildon was built, she went of her own accord and laid the foundation stone, and then gave an address in which she expressed the gladness that God was providing a house for his people to worship in…when the chapel was open she rode 40 miles at her own expense to seek an able minister to open it. And when a dispute arose respecting the settling of the deeds, she went to the owner of the land, and like the noble Queen Esther, pleaded the cause of God and His people.

On her death, a friend of the family – John Cleminson wrote ” I have always looked up to her as one of the most Holy and devoted mothers of Israel. Her zeal for God was always manifested in her regular attendance on all the means of grace. At a time when the prayer meeting was kept up at 5 O’clock every morning in the week, she was generally there with the first and when she exercised in prayer, the power of God was always manifest. the whole of her life was that of the Holy devoted Christian. When the Wesleyan Chapel in New Shildon was built, she went of her own accord and laid the foundation stone, and then gave an address in which she expressed the gladness that God was providing a house for his people to worship in…when the chapel was open she rode 40 miles at her own expense to seek an able minister to open it. And when a dispute arose respecting the settling of the deeds, she went to the owner of the land, and like the noble Queen Esther, pleaded the cause of God and His people.

Her benevolence to the power and cause of God was only bounded by her means, she loved all who love our Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity. She fed the hungry and clothed the naked, and, like her Divine Master, she did good to the bodies and souls of men.”

Jane’s religious zeal might not impress so many now in our largely secular society, but this the early 1800’s and Timothy Hackworth was a personal friend of John Wesley (obviously reflected in the naming of his son!). Yet here is a portrait of John Wesley Hackworth‘s mother, showing her to be a women of strength, compassion, wisdom and initiative and reveals her relationship with Timothy Hackworth as impressively egalitarian for the times!

“Jane Golightly came from a rough farmhouse up in Weardale which Jane, I and my great-nephew visited since the ruins are a still there. A lot of work has been done on the disappearing farms of Weardale. Jane’s father was a weaver and probably a sheep farmer.” Ulick Loring.

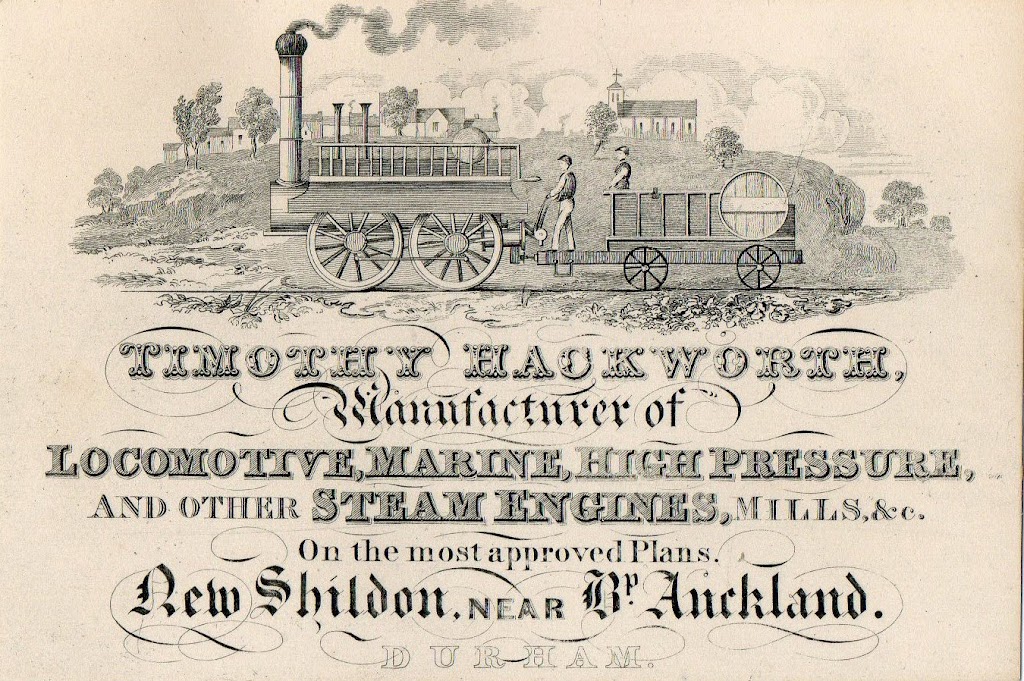

Timothy Hackworth (His father)

|

| Timothy Hackworth |

Timothy Hackworth’s story is well covered on line and in Robert Young’s book Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive. “Born in Wylam 1786, Timothy Hackworth was the eldest son of John Hackworth who was foreman blacksmith at Wylam Colliery until his death in 1804; the father had already acquired a considerable reputation as a mechanical worker and boiler maker. At the end of his apprenticeship in 1807 Timothy took over his father’s position.

In 1824, Hackworth was prevailed upon by George Stephenson to go to the Forth Street works at Newcastle as a ‘borrowed man’ to oversee, amoungst other things, the building of Active (as originally named) but which later became known as Locomotion No 1. By this time John Wesley Hackworth was five years old. Timothy’s brother Thomas had taken over his duties at Walbottle meanwhile. Hackworth only stayed until the end of that year, following which, he returned to Walbottle occupying his time with contract work so as not to deprive his brother of the position. While Timothy was in Newcastle, he had other offers and the idea of starting on his own account had occurred to him and in fact undertook to build some boilers for the Tyne Iron Company. When this was completed Stephenson reopened negotiations, this time to secure him as the resident engineer for the S & D Railway in march 1925 and had the effect of bringing Hackworth to Darlington to meet Edward and Joseph Pease at the Kings Head Inn. None the less Hackworth started up his own Engine manufacture in Newcastle but Stephenson urge the Peases to make him another offer. In 1825 Timothy finally accepted George Stephenson’s proposition to become ‘Superintendent Engineer’ of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, to which he was appointed on 13 May 1825. A post he was to occupy until May 1840.

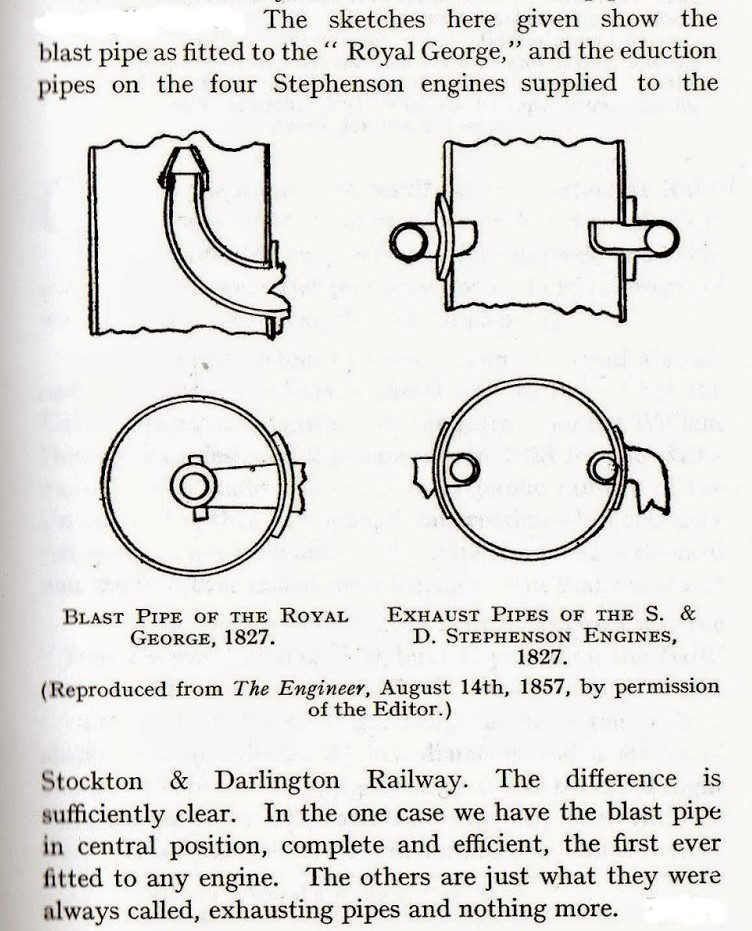

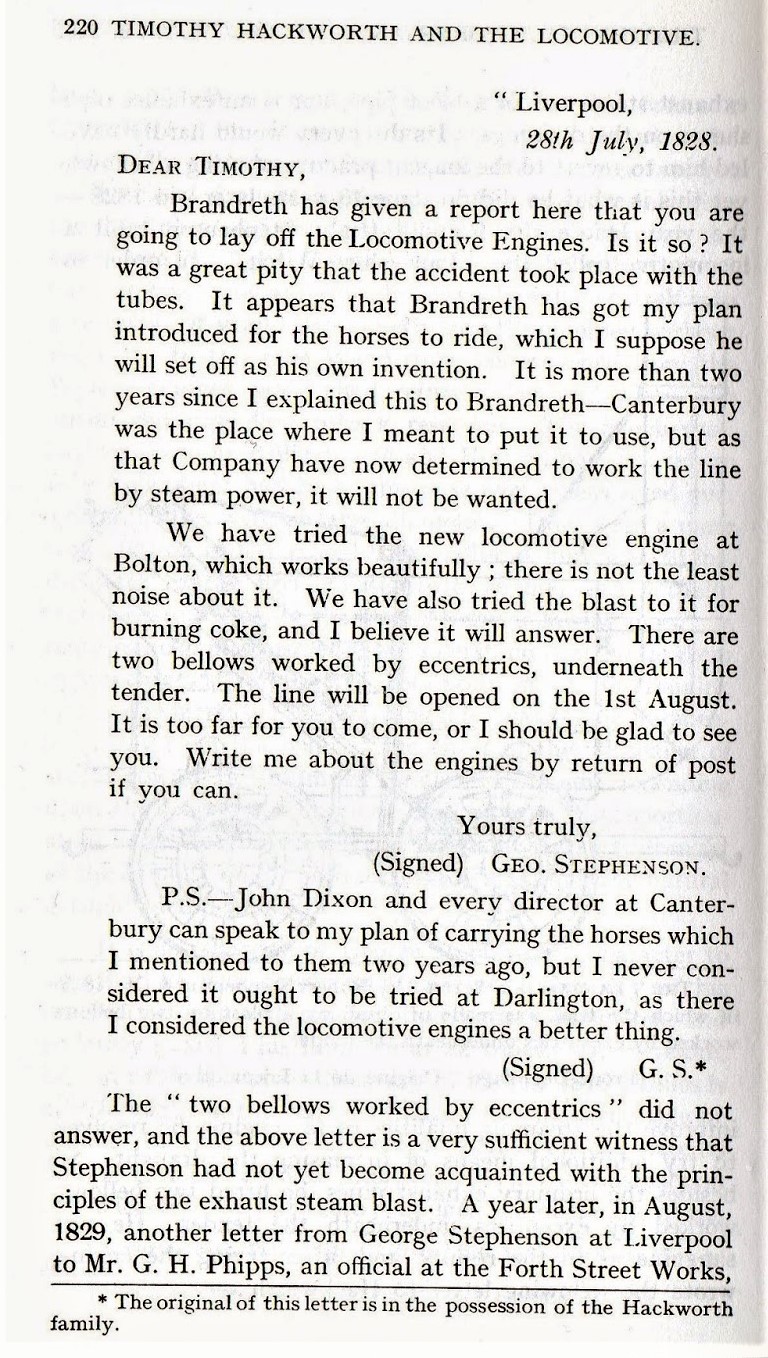

“Hackworth is believed, therefore, to have been influential in the development of the first Stephenson locomotive intended for the Stockton and Darlington Railway during his time at the Forth Street factory. That locomotive, then named Active, now known as Locomotion No 1, was delivered to the railway just before the opening ceremony on 27 September 1825. Three more of the same type were delivered in the following months and difficulties in getting them into operating order were such as to risk compromising the use of steam locomotives for years to come, had it not been for Hackworth’s persistence. This persistence resulted in his developing the first adequate locomotive adapted to the rigours of everyday road service. The outcome was the Royal George of 1827, an early 0-6-0 Locomotive, that among many new key features notably incorporated a correctly aligned steam blastpipe. Hackworth is usually acknowledged as the inventor of this concept. From 1830 onwards the blastpipe was employed by the Stephensons for their updated Rocket and all subsequent new types. Recent letters acquired by the National Railway Museum would appear to confirm Hackworth as the inventor of the device.” read more here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timothy_Hackworth

This letter referred to, from Robert Stephenson to Timothy Hackworth, was until recently in the Joan Hackworth-Weir collection a direct descendant of John Wesley Hackworth and handed down and Joan donated it the museum at Shildon in 2005.). This is a link showing Jane Hackworth Young with the letter- http://www.culture24.org.uk/places+to+go/north+west/manchester/art29660

In 1814, aged 27, Timothy Hackworth married Jane Golightly at Ovingham parish Church at which he’d

|

| Ovingham Church |

been baptized. Robert Young tells us that Jane was a tall, handsome, well educated woman, and the two were almost the same age. She entered into her husband’s work, social, religious and professional with great heartiness and sympathy. Numerous family letters have been preserved and they bear full evidence of the knowledge and interest mutually held in Hackworth’s business and of the affection and complete understanding between the two. In their life together, which extended to 37 years, their children have borne testimony that though they had their full share of anxieties and troubles, yet in their home they were supremely happy and shared all the joys and sorrows pertaining to it.

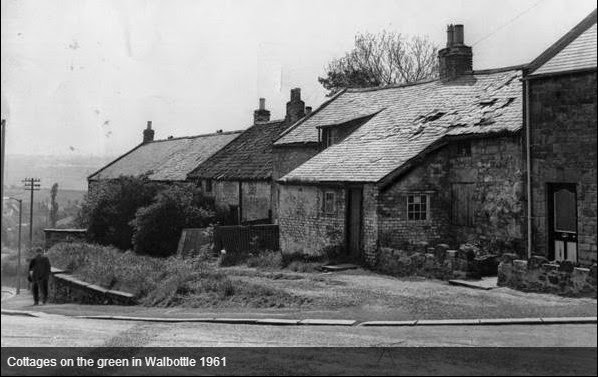

Born in Walbottle 1820

|

| Walbottle 1952 |

John Wesley Hackworth was born at Walbottle, Durham, on May 8th 1820 at 6.30 pm and lived there with his parents until he was 5 years old, when his father, Timothy, joined the Stockton and Darlington Railway. It’s not clear in Robert Young’s book which part of Walbottle Timothy lived Walbottle or North Walbottle. The colliery seems to have been in north walbottle and so one assumes that Timothy lived in North Walbottle, possible in Coronation Road where there were cottages for the mine managers and top people. The back to back terraces for the mine workers are now gone I believe. However I can’t be sure of the location of his residence at this stage, if anyone knows, do get in touch.

Walbottle – a Potted History

“Walbottle is a village in Tyne and Wear. It is a western suburb of Newcastle upon Tyne. The village name, recorded in 1176 as “Walbotl”, is derived from the Old English botl (building) on Hadrian’s Wall. There are a number of Northumbrian villages which are suffixed “-bottle”.(it has been pointed out that suffix Bottle was originally ‘Pottle’ (Latin Potus) meaning small fortified building on the Roman Wall. Source http://newcastlephotos.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/walbottle.html (comments).

Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, refers to a royal estate called Ad Murum near the Roman Wall where, in 653 AD, the King of the Middle Angles, Peada, and the King of the East Saxons, Sigeberht, were both baptised into the Christian faith by Bishop Finan, having been persuaded to do so by King Oswy of Northumbria. Historians have identified Ad Murum with Walbottle.

Ann Potter, the mother of Lord Armstrong, the famous industrialist, was born at Walbottle Hall in 1780 and lived there until 1801. George Stephenson had also worked at Walbottle Colliery. Other notable people born in Walbottle were Thomas Tommy Browell (1892–1955), professional footballer

Richard Armstrong (author) (1903–1986), who wrote for both adults and children. He was the winner of the Carnegie Medal in 1948 for his book Sea Change. He is also known for a biography of Grace Darling in which he challenges the conventional story: Grace Darling: Maid and Myth. He is often described on the cover of his books as “author and mariner”. William Wilson (18 May 1809 died on 17 April 1862 in Nuremberg, Germany). Mechanical Engineer who pioneered railways in Germany in the nineteenth century after working alongside George Stephenson in England. The German Wikipedia article de:William Wilson (Ingenieur) mentions Wilson as being the driver supplied by the Stephenson Loco Works to operate the Bavarian Ludwig Railway.” Source http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walbottle

|

| This was the North Walbottle Colliery |

considerable antiquity, the Duke Pit having been a working shaft upwards of 100 years.

Two basalt or whin dykes run through the colliery; and slip dykes and troubles are very prevalent here. The colliery has been remarkably fortunate in its exemption from explosions. There are three working pits, at which the coals are drawn by an aggregate of 83 horse power. There are also three pumping engines, combining 262 horse power. The waggon-way from the Coronation Pit to the staith at Lemington is about 2 miles long; and the waggons are conveyed thither by horses and inclined planes. The coals are forwarded to the ships by keels. Messrs. Lamb and Co. are the proprietors of the colliery. The coals are known in the market by the names of “Holywell Main,” “Newburn Main,” “Holywell Reins,” and “Holywell Reins Splint.”

Views of the Collieries (1844)” Source http://www.dmm.org.uk/colliery/w025.htm

Timothy Hackworth was born 1786, in Wylam, to John Hackworth who was foreman blacksmith at Wylam Colliery and a celebrated boiler builder and general worker in metals as well for Christopher Blackett. Timothy had started a 7 year apprenticeship under his father and after his father’s death and on finishing his apprenticeship, Christopher Blackett enabled him to take on his father’s position. Thus Timothy stepped into a position of responsibility at an early age. Timothy’s story is told here. In Wylam Timothy gained his formative experience that would set the standard of his future work as an engineer. At 22 he began work on the new steam locomotives that were being introduced at Wylam. He held this position for 8 years.

Writing of those early days when John Hackworth oversaw Timothy’s apprenticeship, John Wesley Hackworth said the youth “gave early indication of a natural bent and aptitude of mind for mechanical construction and research, and it formed a pleasurable theme of contemplation for the father to mark the studious application of his son to obtain the mastery of mechanical principles, and observe the energy and passionate ardour with which he grasped at a through knowledge of his art.“

In 1815 circumstances occurred which led to Timothy Hackworth‘s departure from Wylam.

In 1815 circumstances occurred which led to Timothy Hackworth‘s departure from Wylam.

Timothy had no wish to leave, his employment was congenial. he was in a modest way, comfortably off, it was his native place, and here was born his first child.

John Wesley Hackworth was the 4th of 9 children by Timothy and Jane – Ann, Mary, Elizabeth, John Wesley, Prudence, Timothy, Thomas, Hannah and Jane.

In Wylam, there had been the ‘Dillies‘ which had been deeply interested in and to which he desired to bring to them such a state of efficiency as should show beyond all doubt the their superiority to horse traction..but there were influences at work that affected the comfort of his his permanent residence at Wylam. Blackett had other interests besides the colliery from which he was frequently absent and the reins of authority passed to his viewer, William Hedley. Hackworth, whose views on the sanctity of the Sabbath were well known and had always been respected previously, was requested to do a piece of work at the colliery on the Sunday, to which he firmly declined to be a party. Passing the colliery one Sunday on his way to a preaching appointment, the following conversation took place between a workman and himself.

“Where’s thee gannen?” the man asked. Hackworth replied “I am going to preach” “Is thee not gannen toe to du thee work?” asked the man. “I have other work to do today” Said Hackworth. “Well, if thou’lt not, somebody else will and thou will lose thee job” to which Hackworth rejoined “Lose or not lose, I shall not break the Sabbath.“

The result was that Hackworth had to give up his position, a matter about which he felt very keenly but as to which he never hesitated.

“Timothy Hackworth’s reputation had extended beyond the narrow confines of Wylam village, and he was honoured and respected as a good man and a clever craftsman. When it was known that he was leaving Wylam he received an offer from William Patter, viewer and part owner of Walbottle Colliery, to go there as foreman smith and accordingly he took up residence at Walbottle early 1816. here he remained for 8 years. William Patter, the manager was a man of high character, and a close friendship existed between the head of the colliery and his foreman smith, which remained unbroken during the whole of Hackworth’s service there.

There is little to record of public interest. he followed the even tenor of his way, punctually and efficiently fulfilling his duties secular, social, family and religious. his leisure was spent in study, visiting the sick and similar good works, and he was keenly interested in the people among whom he worked and in whose moral and social advancement he was ever concerned. At Walbottle he made many intimate and lasting friendships, was held in high esteem and won golden opinions throughout the district for his integrity and the many many virtues he possessed. His industrial pursuits were numerous. He was a keen gardener, made a study of horticulture but his chief affections were in the direction of mechanics and he built many steam engines for grinding salt and similar objects, manufactured safety lamps and had always before him the problems connected with the improvement of the locomotive. He did not therefore anticipate a further change of employment, just as he would have been content to remain at Wylam, so at Walbottle the simple life satisfied him. When the time came for his entrance into more absorbing field of locomotion development it was only after much careful thought that he agreed to make the great change.

The Move to Shildon – The Stockton and Darlington Railway.

There is little or no documentary information about John Wesley Hackworth in his formative years, except that which can be gleaned for letters in the Hackworth archives at the York NRM, but given what Robert Young tells us below, his story is very much Timothy Hackworth’s story…

Robert Young tells us in Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive. “from the age of 5, when his

“I saw it opened, was brought up upon it, knew every horse and driver, every director, most of the shareholders, and every noteworthy incident that occurred thereon for the first 20 years. If any man knows anything of its history and working operations, I am the man- to the minutiae.”

Robert Young continues “He was a clever boy but no student of books. While other children were spinning tops, he was spragging the wheels of coal waggons as they reach the bottom of the incline or riding on the locomotives. He went with the Royal George on its final trip and knew as much about it as most of the men and a good deal more than some of them. He thus began his early training as an engineer and never dreamt of any other career. It was part and parcel of his existence and he was a born mechanic. As we shall see, he went off with the first locomotive ever sent to Russia when he was only 16 years of age and on his return completed his apprenticeship with his father, married at the age of 20 and settled down at Shildon.“

Timothy’s first great event was the delivery of Engine No 1. The Stockton and Darlington Railway was launched on Tuesday September 27th 1825. Hackworth was not only the Superintendent of the locomotives but the manager of the line. It was the working of the inclined planes at Etherley and Brusselton that gave him the greatest trouble. The machinery was complicated and cumbersome. Eventually Pease and Stephenson agreed that a change was needed. It was left to Hackworth to deal with this. In 1831 Hackworth designed a compact 80 horse power engine. Robert Young’s book gives more details on this. Locomotion No 1 which launched the S & D line was rebuilt and remodelled at least 3 times by Timothy”

The Birth of the Russian Railway System

Robert Young tells us that –

Blenkinsop steam engine working on the Leeds Middleton Colliery line. This type of engine, of which the first was tried in 1812, derived its motion from a central cog or toothed wheel which engaged with a rack forming part of the rail. This friction was not relied upon and the carrying wheels merely rolled and took no drive..Heavy loads were hauled and the system excited the future Tsar’s interest.”

Blenkinsop steam engine working on the Leeds Middleton Colliery line. This type of engine, of which the first was tried in 1812, derived its motion from a central cog or toothed wheel which engaged with a rack forming part of the rail. This friction was not relied upon and the carrying wheels merely rolled and took no drive..Heavy loads were hauled and the system excited the future Tsar’s interest.” “The need for a more efficient transport system in Russia became more urgent after a series of border skirmishes with Russia’s neighbours and Nicholas was forced into giving his railway project greater priority. The first stage was the construction of a railway from the Baltic port of St.Petersburg to Moscow. Designed to be constructed in short sections, each section was independently financed from private investment and a Czechoslovakian engineer called Franz von Gerstner was invited to oversee the project.”

always financial, not political. The fear of political and social upheavals was raised by the press and occasionally by some officials, but the Tsar and most of his high officials did not consider that a problem. Nicholas I thought that the introduction of technological innovations from abroad would strengthen the existing order, not weaken it. Because of the scarcity of capital and the large amount required for railway construction, the success or failure of these ventures would have a large effect on the Russian state. Thus the tsar and his paternalistic government were much more cautious about economic effects of railways than other countries.

………………………..

And from Russian Locomotives Volume 1 1836-1904 AD Pater and FM Page

Russian Locomotives Volume 1 1836 – 1904 A D de Pater FM Page

John Wesley Hackworth and the Delivery and Launch of the First Locomotive for Russia – 1836.

Russian Locomotive

1956, David Burke wrote that in 1836 “A 16-year old English boy (John Wesley

Hackworth) gave Russia her first railway locomotive. He (and his team) faced

blizzards, wolves, and misfortune, and at the end of his journey, crowds

cheered him, priests blessed him, and he received the Tsar’s congratulations”

Ulick Loring

(the great-great grandson of Timothy Hackworth) comments that “for a young

man reared in the austerity of nonconformist north-east England, to be exposed

to Imperial Russian life must have been a heady experience. It is difficult

nowadays to imagine the contrast between English and Slavic religion and

culture and how it could affect visitors from Western Europe. His locomotive

was the first among several ordered from Western Europe, to arrive at St.

Petersburg. This was on 3rd October 1836 (Russian Calendar).”

The duty of

introducing the locomotive to Russia devolved upon Timothy Hackworth’s eldest

son, John. Such a journey at that time was a perilous proposition and Timothy’s

decision to send his son couldn’t have been taken lightly! It may have been

because both Timothy and Thomas were under considerable pressure and Thomas had just got married to a French

woman, Adele Celestine Hennon, but

as Robert Young says John Wesley Hackworth was ‘a well set up youth, nearly

as tall as his father, and a keen and clever engineer, absorbed in his

profession and in appearance, much older than his years.’

Two engines

were outsourced to the Hackworth’s Soho works, New Shildon but only one

was built,

but was the first to be delivered to Tsar Nicholas 1. George Turner Smith says,

“In effect, the engine was a typical Stephenson 2-2-2 ‘Patentee…The engine

was crated up and transported on a modified flatbed wagon, along the S&D

rails to Port Darlington in Middlesbrough…The locomotive was loaded on to the

brig – Barbara”

(George Turner Smith – Thomas Hackworth (Locomotive Engineer) 2015 p10)

On the 17th

September 1836, The Durham Advertiser reported –

“On

Thursday, 15th September, a large and powerful locomotive engine, built by

Timothy Hackworth of New Shildon for the Emperor of Russia was shipped on board

the ‘Barbara’ at Middlesbro’. This engine is constructed on an improved

principle and finished in the best manner. She

has been tried on the premises and propelled at the rate of 72 miles per hour.

It is said that this machine and the similar one built at Newcastle, will on

their arrival at St. Petersburg, have cost the Emperor upwards of £2,000 each.

Who, a few years ago, would have dreamed of the exportation of machinery from

the River Tees? This engine is for travelling on the railroad from St.

Petersburg to Pavlovsky where stands one of the country palaces of his Imperial

Majesty.”

(Railcentre website http://www.railcentre.co.uk/RailHistory/Hackworth/Pages/HackworthPage5.html#ImageLeft03_ID )

The locomotive

arrived at Port Darlington, Middlesbrough along with Hackworth’s team of

engineers. It is assumed the Barbara would be a brig but nothing much is known

about it. For any Middlesbrough historians wanting to do some research on the

ship, the records from Customs House, Middlesbrough are now in Teesside

archives.

Six years

earlier, Timothy Hackworth designed the coal staithes in Middlesbrough, in 1830, and there is a

plaque at Middlesbrough docks placed there by Jane Hackworth-Young , great great

grand-daughter of Timothy Hackworth,

in 1981.

Local

historian, George Markham Tweddell gave a description of the coal staithes in

1890.

“The railway

to Middlesbrough was opened December 20th, 1830, with a train of

passengers and

coal, one immense block of “black diamonds” from the Old Boy Colliery

figuring conspicuously, which, when broken, was calculated to make two London

chaldrons. Staithes had already been erected to load six ships at one time, and

the visitors witnessed the loading of the Sunnyside, under the management of

Mr. William Fallows, then in his thirty-third year, who the year previous had

been appointed agent to the Stockton and Darlington Railway at Stockton. The mode of loading the vessels laying along

the low-banked river was very ingenious. Each waggon of coal was run on to a

cradle, then raised by steam power to the staithes, and lowered by

“drops” to the decks, a labourer descending with each waggon, undoing

the fastening of the bottom, and thus allowing the coals to fall at once into

the ship’s hold, when he ascended with the empty waggon, which was returned to

the railway with the same machinery, in the principal gallery of the staithes,

covered in and adorned for the festive occasion, and lighted by portable gas –

the first ever burnt in Middlesbrough – a table, 134 yards long, loaded with

provisions, supplied the needed bodily refreshment to nearly six hundred hungry

spectators, all of whom entertained glowing hopes of the prosperity of the new

venture.”

(George Markham Tweddell in his History of Middlesbrough in Bulmer’s North Yorkshire Directory 1890 – http://georgemarkhamtweddell.blogspot.com/2012/12/tweddells-history-of-middlesbrough-1890.html

It was

previously surmised that John Wesley Hackworth travelled with

the team from Shildon to Middlesbrough but in searching the Hackworth archive we discover that John

Wesley Hackworth was traveling to

London with his father, on business and intended to board a ship in London to

catch up with the team in Hamburg. He missed the initial connection, but managed

to board a later ship and reunite with the team.

A description

of the Letter from Timothy Hackworth (Guild Hall Coffee House) to Jane Hackworth

22nd September 1836 reads “we were

to (sic) late in reaching London the vessel had been gone 15 minutes. One Mr Kitching from Lancashire has to go to

St Petersburg to fix two weighing machines, he together with his niece and son

John all go on board on Friday night and sail for Hamburg on Saturday morning

and I think of coming home by Majestic…….’

(Hackworth Family Archives NRM York letter dated 22nd September 1836 (TH9385) https://www.railwaymuseum.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-04/Hackworth%20Family%20Introduction%20%26%20Archive%20List.pdf

At that time,

the Baltic was frozen over so the team had to travel from Hamburg through 500

miles of frozen desolate country with wooden sledges, before the spires of St.

Petersburg came into view. David Burke, who had sight of the lost John

Wesley Hackworth diary of the trip, says “Blizzards nearly blinded them,

wolves attacked them and only by whipping the horse teams into a frenzy did

young Hackworth and his team escape the snapping jaws.” And Robert Young

adds that “the weather was so severe that the spirit bottles broke with the

frost”

Clearly in

1836, delivering a locomotive was no easy task but it was by no means the end

of their troubles. While assembling the locomotive in St. Petersburg, a

cylinder cracked and with no workshops in the city capable of fixing it,

Hackworth’s foreman George Thompson heroically took the cylinder from St.

Petersburg to Moscow, a distance of some 600 miles, to the armoury where they made a pattern for

the cylinder, got it cast, bored out and fitted, returned to St. Petersburg,

and fixed it in the engine.

The Launch

of the Russian Locomotive

David Burke tells us “In November 1836 bells pealed in St. Petersburg, guns boomed,

and

the line was opened with great crowds cheering, gaping Russians who had never

seen an ‘Iron horse’ before’. John Wesley Hackworth drove his puffing, hissing

charge into Tsarskoye-selo where the Tsar Nicholas 1 and his family and

generals waited to see him arrive. Not that the opening of the first railway in

once Holy Russia was as simple as that – a score of orthodox priests descended on the engine with crosses, candles,

censers, and holy water to perform the blessing ceremony”. “They

splashed me in the process” Hackworth wrote in his diary.

Robert Young elaborates “This was the baptismal ceremony of consecration according to the

rites of the Greek Church done in the presence of an assembled crowd. Water was

obtained from a neighbouring bog or “stele” in a golden censer and sanctified

by immersions of a golden cross amid chanting of choristers and intonations of

priests, while a hundred lighted tapers were held round it. This was followed

by the invocation of special blessings upon the Tsar and Imperial Family, and

fervent supplications that on all occasions of travel by the new mode, just

being inaugurated, they might be well and safely conveyed. Then came the due

Administration of the Ordinance by one priest bearing the holy censer; while a

second, operating with a huge brush and dipping in the censer, dashed each wheel

with the sign of the cross, with final copious showers all over the engine, of

which John Hackworth was an involuntary partaker.”

Hackworth

related in his diary how he was introduced to the Tsar who told him of a visit

to England in 1816, when he had witnessed the running of Blenkinsop’s engine on

the colliery line from Middleton to Leeds. The Tsar added some complimentary

remarks regarding the new locomotive, saying he ‘could not have conceived it

possible so radical a change could have been effected within the last 20 years.

The Tsar also told him that “It was an occasion of great progress and other

‘Iron horses’ would surely spread across the nation.”

The Hackworth

team, despite the delays and difficulties in getting there and in travelling to Moscow for the repair, were the first to launch. The launch,original scheduled for September was delayed until November 1836 to

enable the other teams to set up.