The

Locomotive and its Literary Influence.

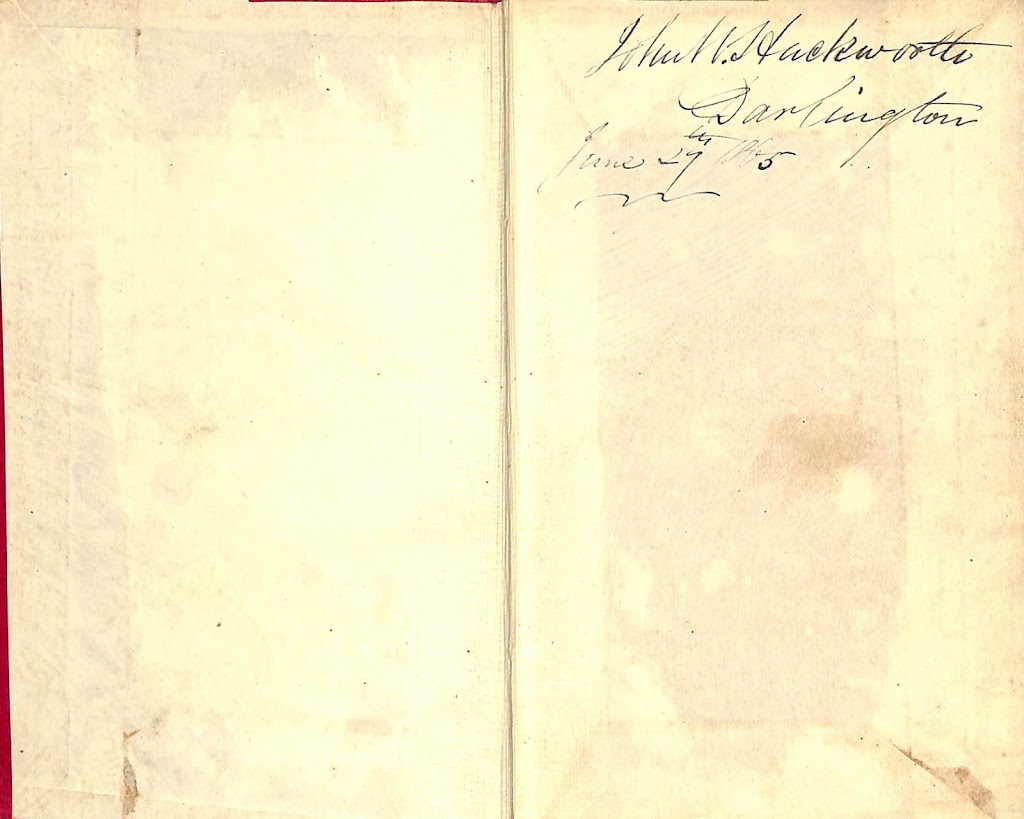

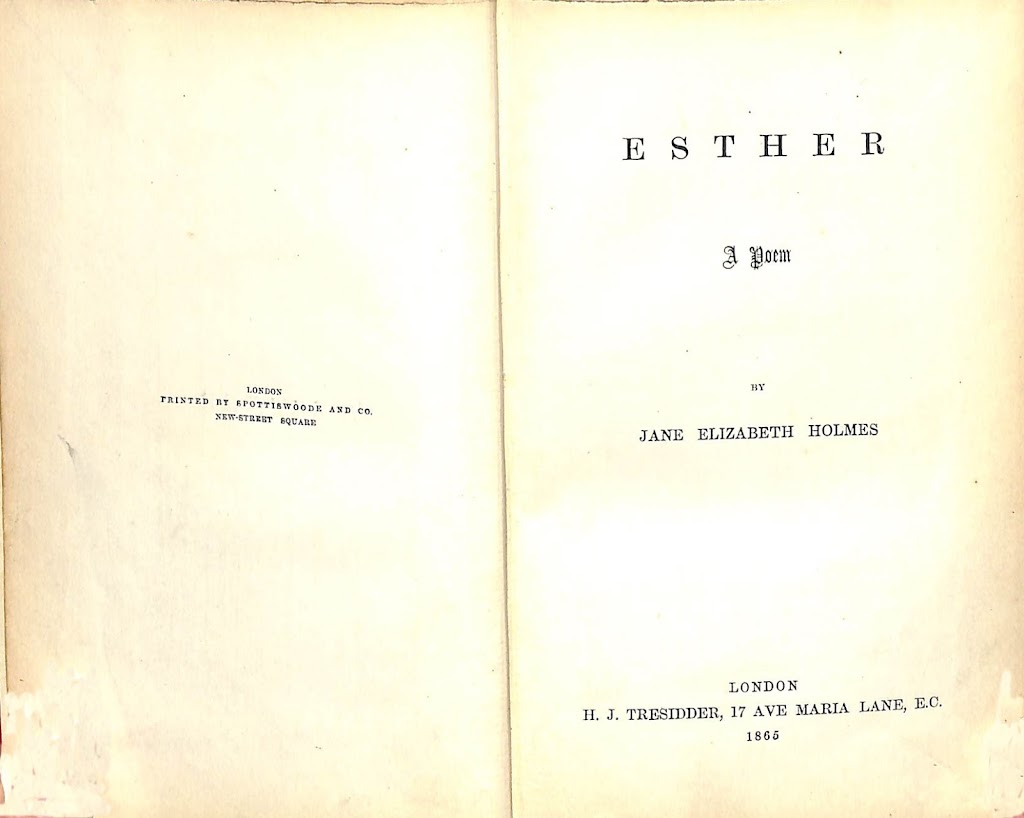

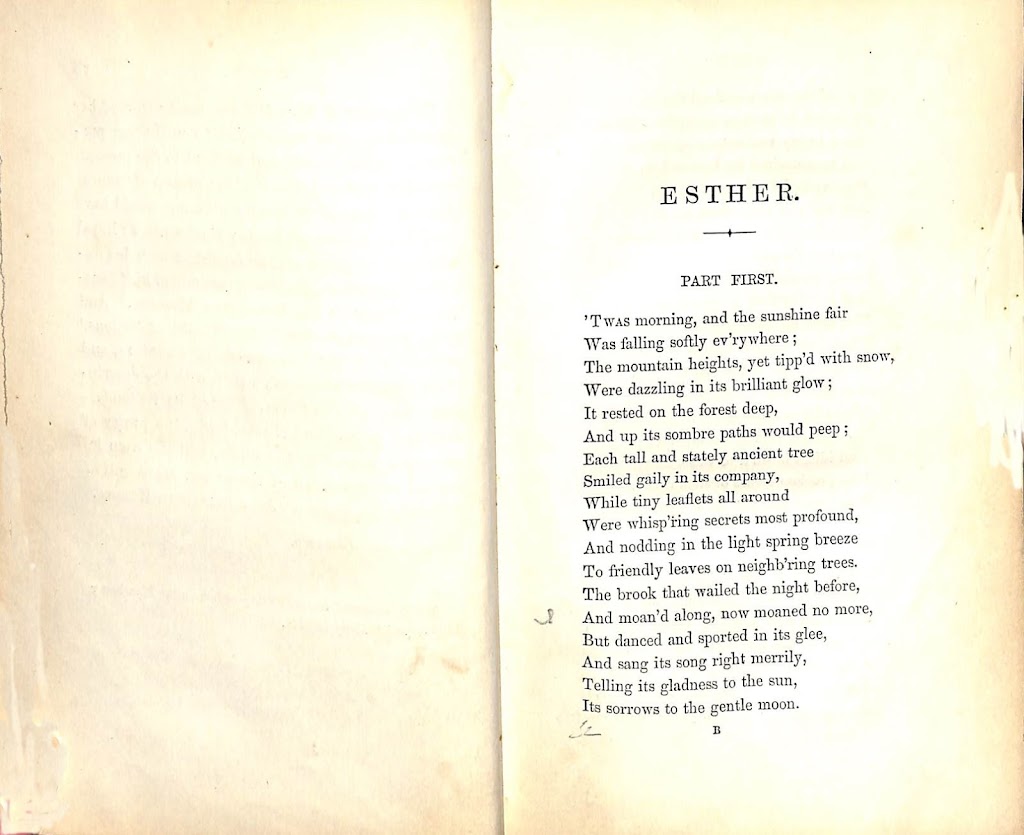

This literary section is probably more of an indulgence on my part, as it doesn’t directly engage with John Wesley Hackworth, but I think it’s an interesting divulgence before continuing with his life and work.

The former

Green Dragon Museum in Stockton had a documentary on loop that showed how the

birth of the railways influence the birth of the blues, with its harmonica

whistles and railway blues / symbolism. The film may be at Preston Park now. (More here).

https://joanhackworthweircollection.blogspot.com/2014/05/the-railroad-and-birth-of-blues-social.html

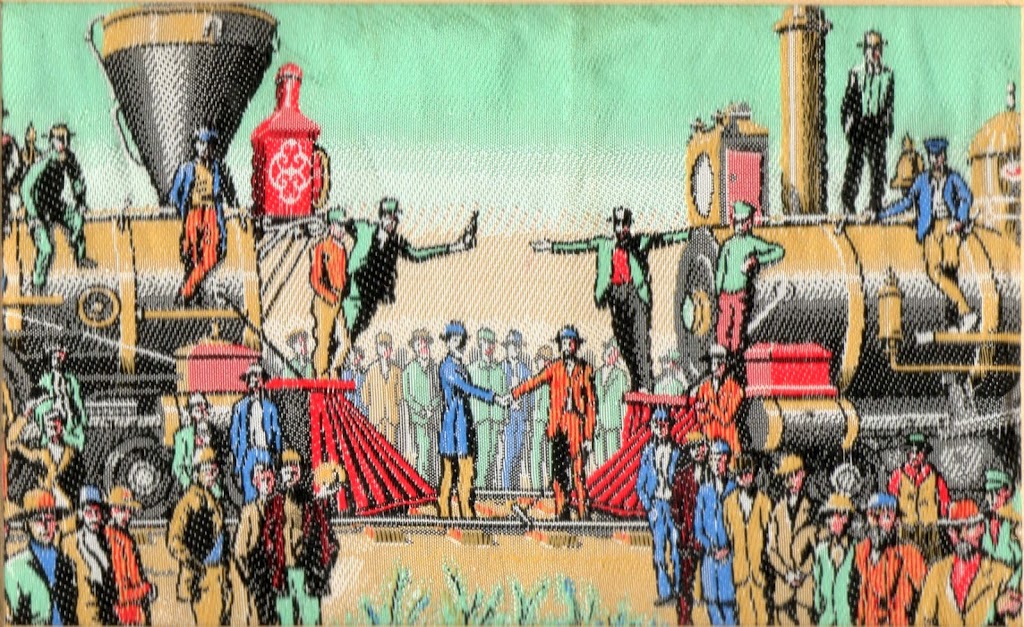

According to Jane Hackworth-Young new research suggests that Timothy Hackworth influenced the building of the first engines in America. The birth

of the railways had a huge impact on music and literature – Charles Dickens

(known to use the new form of transport) seems to have set the ball rolling

with his novel Dombey and Son (1846-48) and later Mugby Junction. Later there

was Émile Zola’s La Bête Humaine (1890) and The Railway Children by E. Nesbit was published

in 1906, but what of Russia literature?

“Dickens employs railways as image and plot device in Dombey and Son well represent both the range of effects they had on Victorian Britain and its usefulness as image and analogy.

Dickens recognized the ways this new transportation technology could affect Victorian cities for the better, ridding them of their worst slums and leading to new housing for the poorer classes. He also presents those who work on the railway, particularly engine drivers, as valued members of society — solid citizens.“

“A curse upon the fiery devil, thundering along so smoothly, tracked through the distant valley by a glare of light and lurid smoke, and gone! He felt as if he had been plucked out of its path, and saved from being torn asunder. It made him shrink and shudder even now, when its faintest hum was hushed, and when the lines of iron road he could trace in the moonlight, running to a point, were as empty and as silent as a desert.” from Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens

“As the belated traveller plodded up and down, a shadowy train went by him in the gloom which was no other than the train of a life. From whatsoever intangible deep cutting or dark tunnel it emerged, here it came, unsummoned and unannounced, stealing upon him and passing away into obscurity.“

“Guard! What place is this? Mugby Junction, sir. A windy place! Yes, it mostly is, sir. And looks comfortless indeed!”

“Red hot embers showering out upon the ground, down this dark avenue, and down the other, as if torturing fires were being raked clear; concurrently, shrieks and groans and grinds invading the ear, as if the tortured were at the height of their suffering. Iron-barred cages full of cattle jangling by midway, the drooping beasts with horns entangled, eyes frozen with terror, and mouths too: at least they have long icicles (or what seem so) hanging from their lips. Unknown languages in the air, conspiring in red, green, and white characters. An earthquake accompanied with thunder and lightning, going up express to London.” Quotes from Mugby Junction Charles Dickens

“This was the 4.25 train for Dieppe. A stream of passengers hurried forward. One heard the roll of the trucks loaded with luggage, and the porters pushing the foot-warmers, one by one, into the compartments. The engine and tender had reached the first luggage van with a hollow clash, and the head-porter could then be seen tightening the screw of the spreader. The sky had become cloudy in the direction of Batignolles. An ashen crepuscule, effacing the façades, seemed to be already falling on the outspread fan of railway lines; and, in this dim light, one saw in the distance, the constant departure and arrival of trains on the Banlieue and Ceinture lines. Beyond the great sheet of span-roofing of the station, shreds of reddish smoke flew over darkened Paris.” From Émile Zola’s La Bête Humaine (1890)

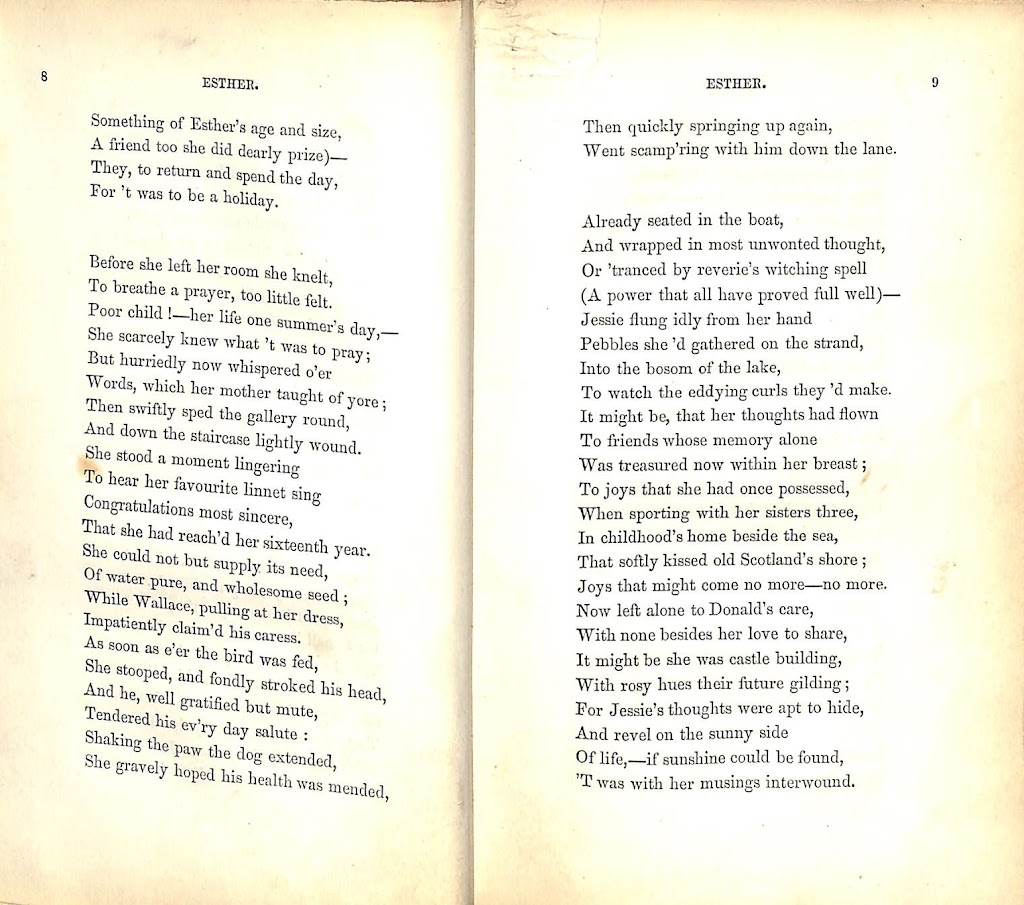

Never before had they passed close enough to a signal-box to be able to notice the wires, and to hear the mysterious ‘ping, ping,’ followed by the strong, firm clicking of machinery.

The very sleepers on which the rails lay were a delightful path to travel by—just far enough apart to serve as the stepping-stones in a game of foaming torrents hastily organised by Bobbie.

Then to arrive at the station, not through the booking office, but in a freebooting sort of way by the sloping end of the platform. This in itself was joy.

Joy, too, it was to peep into the porters’ room, where the lamps are, and the Railway almanac on the wall, and one porter half asleep behind a paper.”

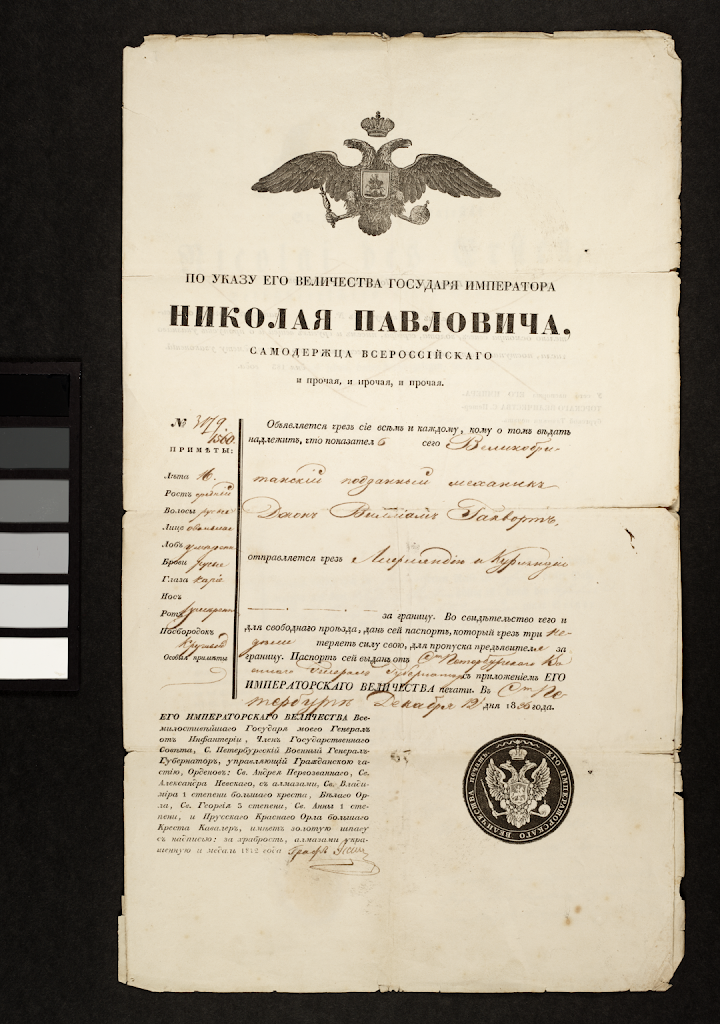

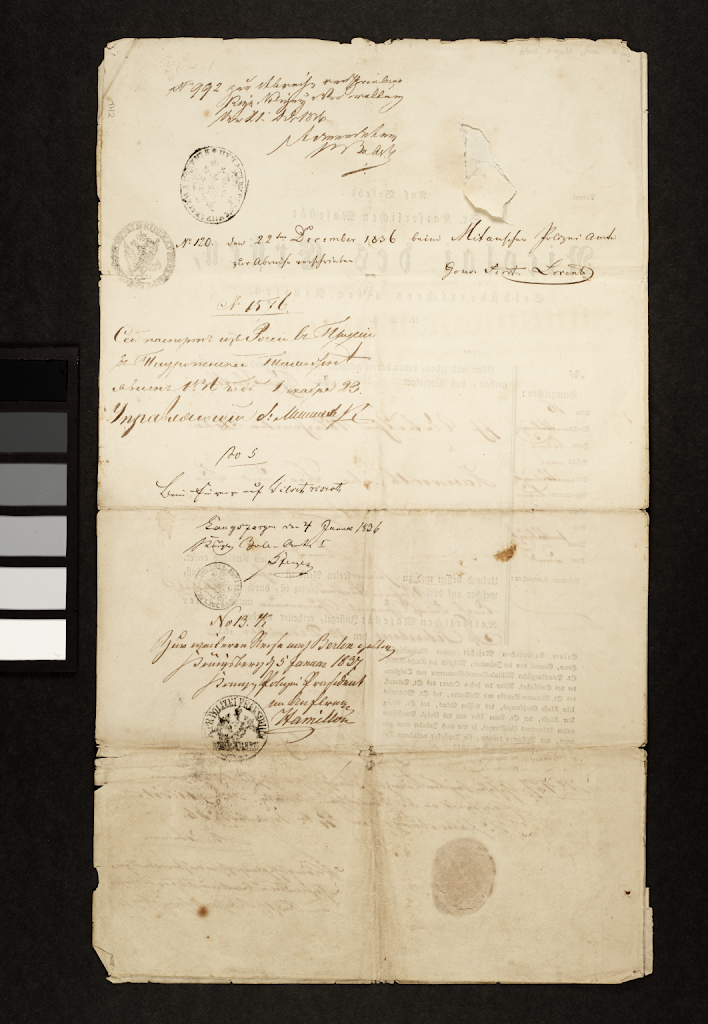

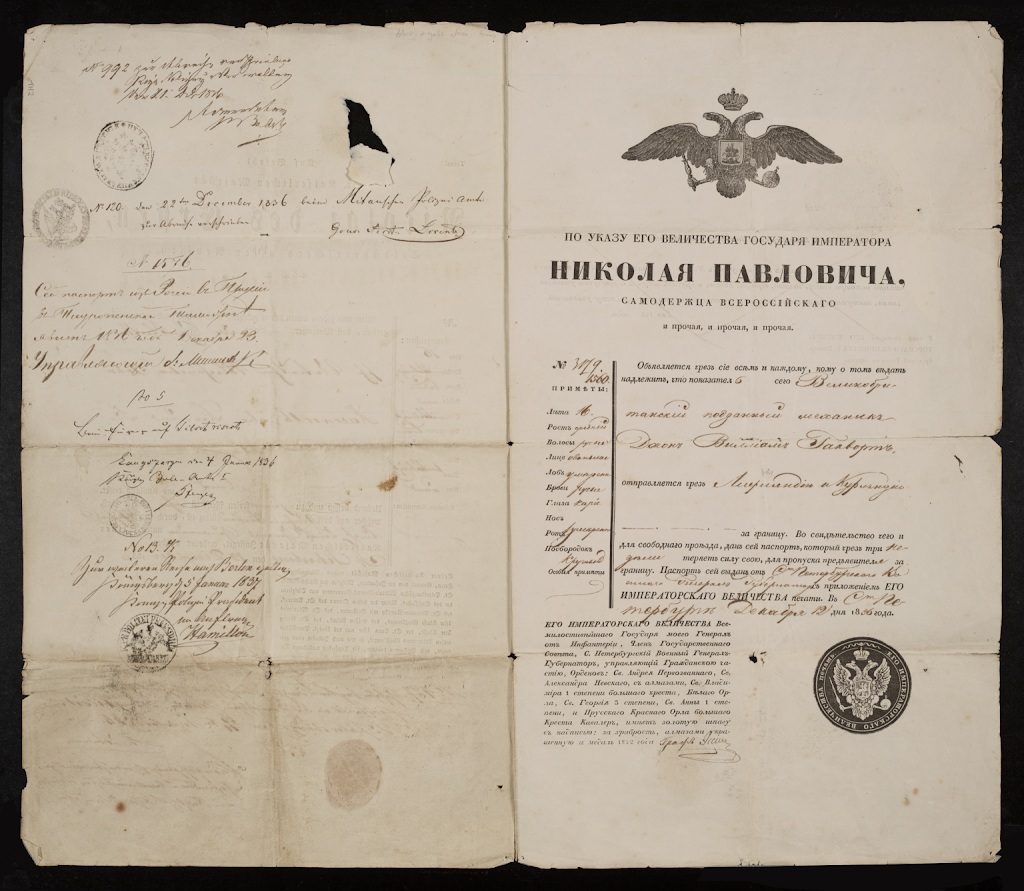

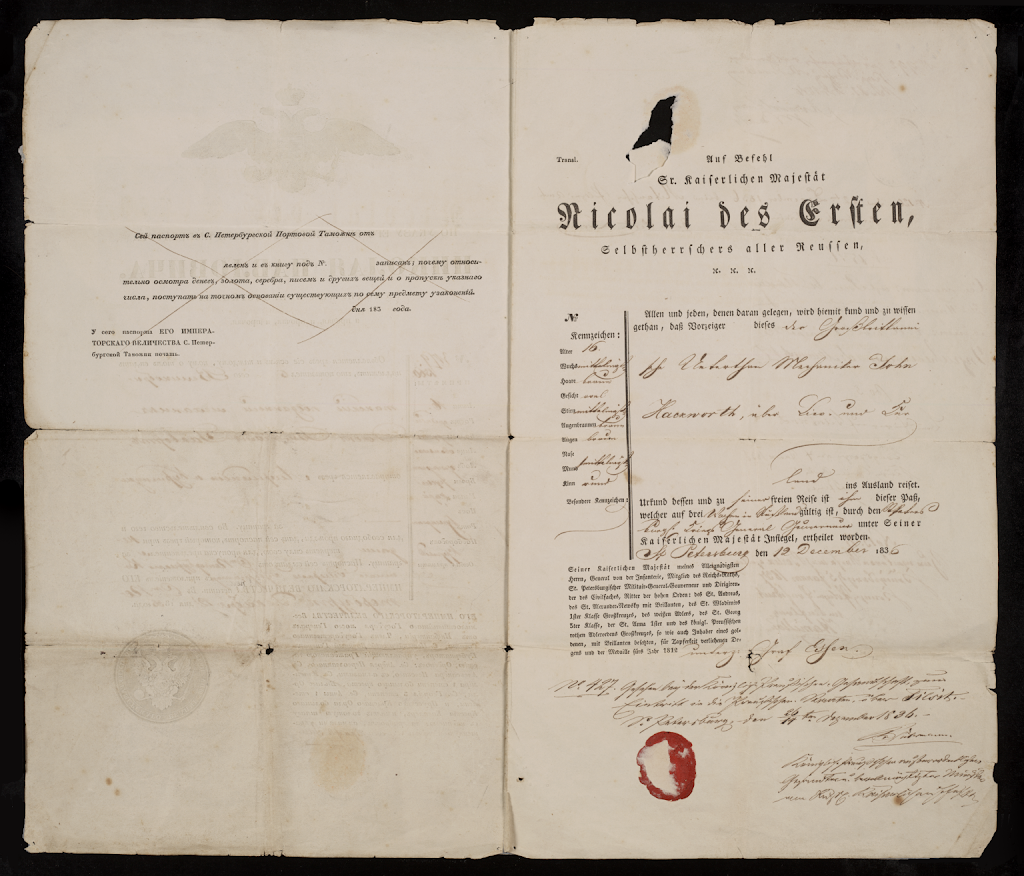

From Pushkin

to Tolstoy

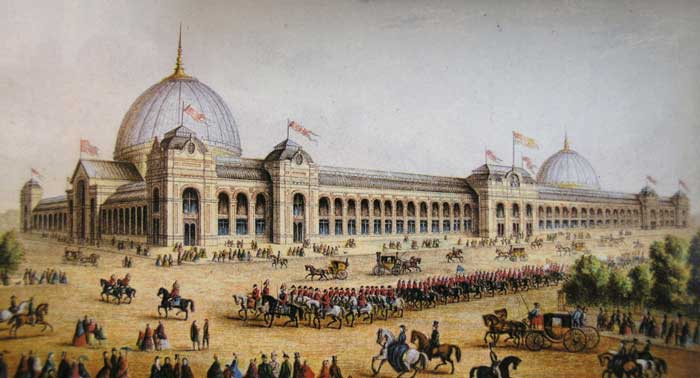

The town of

Tsarskoye-Selo (meaning Tsar’s village) was renamed Pushkin in 1937, one

hundred years after John’s return to England, and it was in honour of the

Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, who studied at the Imperial Lyceum there 1811 to 1817.

There’s no evidence to suggest John Wesley Hackworth met or was aware of

Pushkin but it’s probable the Russian poet and his wife were at the launch. If

so, and had he lived, it’s tempting to think the event might have found its way

into his work.

Pushkin was a poet,

playwright, and novelist, considered by many to be the founder of modern

Russian literature. Born into Russian nobility in Moscow, he published his

first poem at 15 and was widely recognized by the literary establishment by the

time of his graduation from

the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum. His controversial poem

“Ode to Liberty”, led to him being exiled under Tsar Alexander 1 and

under strict surveillance of the Tsar’s political police, unable to publish

freely. Pushkin married Natalia Pushkina and they became regulars of court society.

Among her admirers was Tsar Nicholas 1 for whom John delivered the engine. It’s

interesting to note that Pushkin was around the Summer Palace at that time but

moreover, just as in Pushkin’s famous novel in verse, Eugene Onegin, that ended

with a lovers duel, in November 1836, while John was there, Pushkin faced a

rumour that Georges d’Anthès (a French military officer and politician) was

having an affair with his wife. He received several copies of a “certificate” nominating him “Coadjutor of the International Order of Cuckolds.” Pushkin immediately challenged Georges d’Anthès to a duel

in November which was delayed until February 1837 and sadly then Pushkin was fatally

wounded at the age of 37. Strange to think that John Wesley Hackworth’s greatest moment was shared in close proximity in Tsarskoye-Selo with Alexander Pushkin – the greatest Russian Poet’s most tragic moment!

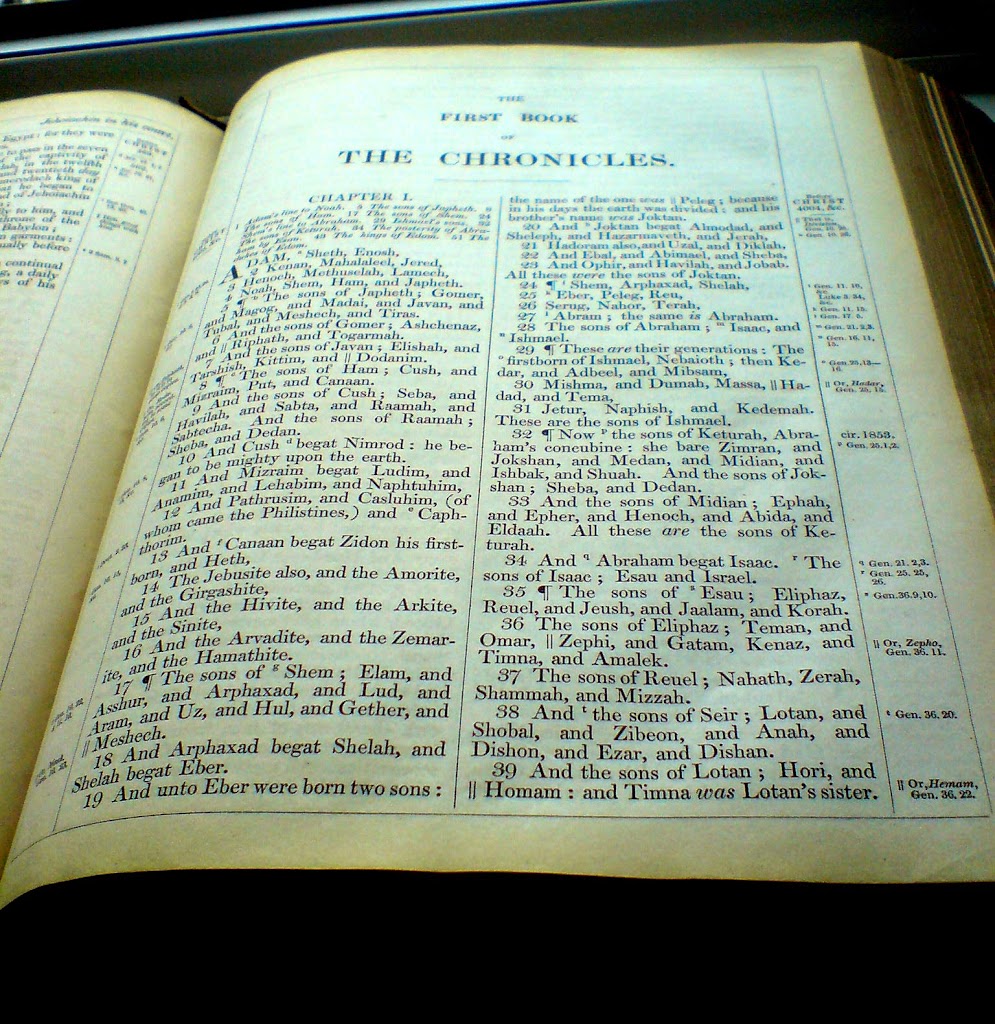

By 1860,

Dostoevsky had mentioned St. Petersburg station in his classic novel ‘Crime and

Punishment’, but it was down to Leo Tolstoy, an aristocrat, to produce the

first Russian novel evoking the railways. Most Russian aristocrats, were

opposed to the railways, thinking it would lead men to move about too freely

and might assist rebellion! That would come soon enough! Tolstoy’s novel Anna

Karenina, published 1878, was one of the earliest novels after Dickens to

incorporate the theme of trains and railroads as a central motif. Tolstoy was

not a fan of trains and went as far to say, “The railroad is to travel as a

whore is to love” Anna Karenina is full of important scenes on trains and

in stations, but they also serve as a means of progressing the storyline.

“Tolstoy

felt that trains were destroying the old Russian way of life in favour of a new

industrial and capitalistic Russia, while moving away from traditions and

simplicity. Anna Karenina is a victim of her love affair, committing suicide by

throwing herself under a train, while the theme of trains and railroads pierces

the entire story. Tolstoy incorporates the symbols of railroads and trains as

motifs of tragedy

brought by the advancing progress of Western technology in

Russian society, the destructive nature of trains, and how characters such as

Levin serve as a reminder of how trains are destroying closeness to nature and

old true values.”

“The engine had already whistled in the distance. A few instants later the platform was quivering, and with puffs of steam hanging low in the air from the frost, the engine rolled up, with the lever of the middle wheel rhythmically moving up and down, and the stooping figure of the engine-driver covered with frost. Behind the tender, setting the platform more and more slowly swaying, came the luggage van with a dog whining in it. At last the passenger carriages rolled in, oscillating before

coming to a standstill.

A smart guard jumped out, giving a whistle, and after him one by one the impatient passengers began to get down: an officer of the guards, holding himself erect, and looking severely about him; a nimble little merchant with a satchel, smiling gaily; a peasant with a sack over his shoulder.”

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy