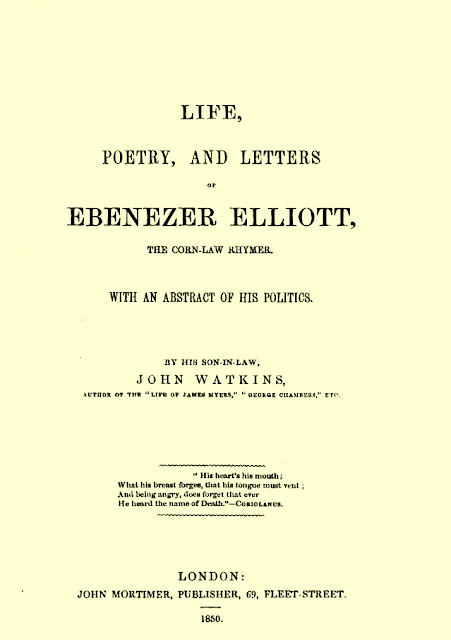

This article was submitted by Professor of Social history Malcolm Chase, at Leeds University who was assisting Paul Tweddell and I, in researching George Markham Tweddell’s relation to the Chartist movement and Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer. John Watkins (Chartist, poet, playwright), based in Whitby, and who was imprisoned for sedition after promoting Chartism in Stockton, married Ebenezer Elliot‘s daughter and Elliott’s biography. Although I’ve not established any direct links between Tweddell and Watkins, given his wide social networking (long before the days of the internet), and the close proximity of location and that they both contributed poetry to the Northern Star, it is likely that they knew of each other at least. Tweddell had corresponded with Ebenezer Elliott and exchanged poetry with Tweddell having invited Elliott to contribute his Yorkshire Miscellany. Watkins married Elliott’s daughter and wrote his biography, that increases the chances of a connection, but so far I’ve not come across any direct mention in Tweddell’s work.

(available to read on line or download free by clicking pdf in the sidebar.

http://openlibrary.org/books/OL23312977M/Life_poetry_and_letters_of_Ebenezer_Elliott_the_Corn-law_rhymer)

JOHN WATKINS (1808-1858)

Poet, Playwright and Chartist by Malcolm Chase (Professor of Social History, Leeds University)

John Watkins is a largely forgotten writer from north-east Yorkshire, with strong Teesside connections. He wrote around thirty books and two or three plays. If his poetry and often-substantial newspaper articles is included his output runs to around 150 pieces, placing him among the most prolific nineteenth-century authors from this region. It is not just the quantity of his output that is important but the place of much at the centre of Chartism, the great movement for parliamentary reform that dominated British politics in the late 1830s and 1840s. The short biography that follows is based on Malcolm Chase‘s entry on Watkins in the Dictionary of Labour Biography, volume 12, edited by Keith Gildart and David Howell (Palgrave, 2005).

John Watkins was born on 6 April 1808, the eldest son of Francis and Christina Watkins of Aislaby Hall, Whitby, and nephew of the Whitby author William Watkins. Details of his education are unclear until his mid-teens when he was articled to a Whitby firm of solicitors, Preston &Walker. Here he formed a close friendship with a fellow clerk, James Myers, who inspired him to study literature and become a poet and author. The latter’s death from consumption in 1829 much affected Watkins and the following year he published The Remains of James Myers, of Whitby, with an Account of his Life (1830). He followed this nine years later with Memoirs of the Talents, Virtues and Misfortunes of James Myers (1839).

Watkin’s first biography of Myers was preceded by the first edition of his Stranger’s Guide through Whitby and the Vicinity (1828; three later editions). It was followed by Scarborough Tales (1830) and contributions to the local literary journals, Whitby Repository and Whitby Magazine. The first indications of a political career that was to be built on verbal assaults of opponents followed an irretrievable breakdown in his relation with James Walker, partner in the solicitors where he worked. This resulted in A Letter to the Lawyers (1834), a pamphlet considered so libelous that no Whitby printer would touch it (it was finally published in Beverley). Watkins returned to the same theme five years later with a crude satire, Padfoot (1839). However, his career only took shape with his entry into politics with A Letter to the Inhabitants of Whitby, Particularly Addressed to the Middle Classes, on the Decline of the Town, (1838). Referring in his introduction to the absence of a ‘truth-telling Newspaper‘ in Whitby (p.3), his picture was of a town divided against itself, with the traditional local economy pitched against new developments promoting tourism. Watkins predicted that proposed street improvements would ruin Whitby, since they were costly, unnecessary and forced through only to smarten the town in readiness for the arrival of the railway. ‘Whitby is a town for business, not for pleasure . . . Industry raised the town and extended its trade – wealth came and lay down idly on the lap of luxury‘ (p.21). He was particularly critical of Aaron Chapman, the Tory MP for Whitby, alleging he bought shares in the railway, knowing they were over priced, solely to boost his standing in the town. Others, less able than he to sustain the loss, were thus encouraged to buy shares at an inflated price. ‘Want, woe, and crime are the blessings of Toryism. The name of Tory ought to be odious to our sight and hearing; for its nature is execrable‘ (p.25).

A Second Letter to the Inhabitants of Whitby, calling upon them to Release the Town from the Tyranny of Toryism (1838) followed. It was aimed at a wider audience than the first and addressed national issues as well as local ones. It also introduced a religious note: ‘nothing is so antichristian as Toryism” (p.28), opined Watkins, also comparing it to ‘devilism‘ (p.45). Increasingly, Watkins was to be preoccupied with the radical import of Christianity, a theme to which he returned that year in his Memoir of Joseph Bower (1838) in which he defended a self-taught poet from Newholm, reputedly an atheist, as a deist and ‘Christian philosopher‘ (p. 36). However, it was Chartism – the great movement for parliamentary reform – that crystalised his political outlook. Its founding text, The People’s Charter, was published in London in May 1838 and its spirit was quickly apparent in Watkins’ Third Letter to the Inhabitants of Whitby . . . By a Friend of the People:

‘There are about 10,000 inhabitants in Whitby – about 350 of these possess the elective franchise, and an oligarchy, consisting of some 70, rule the rest against their will; that is, make slaves of them. . . . Labour depends upon capital for employment, and the capitalist will not employ the labourer unless he renounce his birthright – the poor man must choose between slavery and starvation. . . . Reformers should unite and form a separate communion. . . . Submit to the laws; but be not slaves of the Tory tyrants that make such laws. Form a branch association with the working men of other towns – procure the People’s Charter to be granted, and you can repeal bad laws, and make good ones in their stead’ (pp, 10, 27).

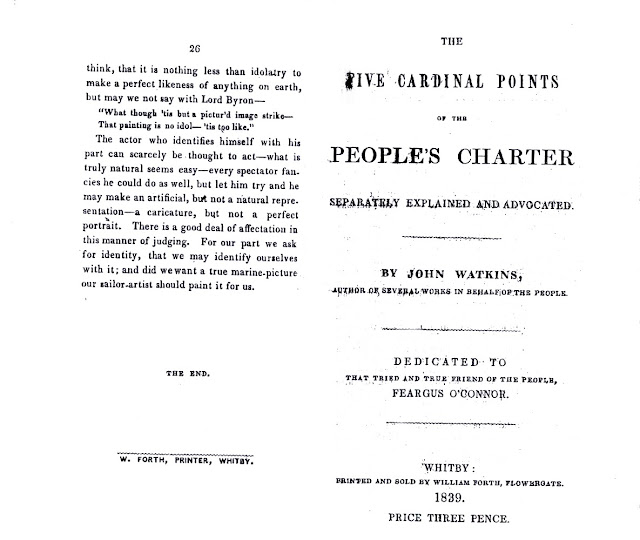

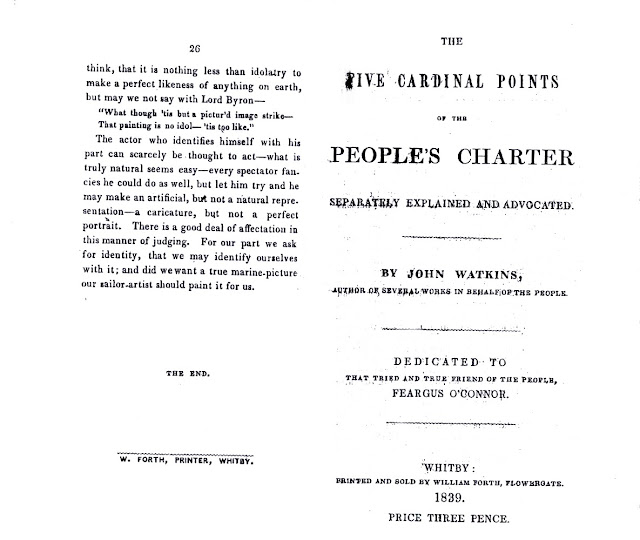

Watkins extended his argument early the following year in The Five Cardinal Points of the People’s Charter, a forty page pamphlet of striking force and clarity. Watkins marshalled all the arguments circulating in favour of the Charter at this time (though he ignored its call for equal electoral districts, which would almost certainly have disfranchised small parliamentary boroughs like Whitby). Labour is the source of all wealth and thus a form of property just like land with which it should have equal rights. The aim of the Charter is to complete a political process begun with Magna Charta and produce a democratic, accountable parliament that will cleanse the country of corruption and eliminate ‘factious government or class legislation‘ (p.3). The Christian ethic, by now a central aspect of his politics, is reiterated: ‘ Charterism is a secondary Christianity – Christians must be Charterists‘ (p.30) and this leads him to develop the concept of a ‘moral charter, as well as a political Charter . . . namely, honesty, industry, knowledge, frugality, and temperance‘ (p. 35).

Watkins extended his argument early the following year in The Five Cardinal Points of the People’s Charter, a forty page pamphlet of striking force and clarity. Watkins marshalled all the arguments circulating in favour of the Charter at this time (though he ignored its call for equal electoral districts, which would almost certainly have disfranchised small parliamentary boroughs like Whitby). Labour is the source of all wealth and thus a form of property just like land with which it should have equal rights. The aim of the Charter is to complete a political process begun with Magna Charta and produce a democratic, accountable parliament that will cleanse the country of corruption and eliminate ‘factious government or class legislation‘ (p.3). The Christian ethic, by now a central aspect of his politics, is reiterated: ‘ Charterism is a secondary Christianity – Christians must be Charterists‘ (p.30) and this leads him to develop the concept of a ‘moral charter, as well as a political Charter . . . namely, honesty, industry, knowledge, frugality, and temperance‘ (p. 35).

There was no tradition of political radicalism in Whitby and Watkins was only ever a minority voice there. According to the Yorkshire Gazette (2 Feb 1839), only thirteen attended the first meeting of the Working Men’s Association that Watkins established in the town. (Its title imitated Chartist organisations that were springing up across urban England and lowland Scotland at this time). The venture seems to have picked up during the summer, however, and by June the Association had a permanent base on the pier where Watkins lectured weekly. This also doubled as the Working Men’s Chapel, where Watkins preached each Sunday and for which he wrote and had published a twelve-page booklet of hymns. ‘The service was conducted with as much decency and decorum as though the congregation had been in the habit of assembling there for a number of years‘, wrote one newspaper reporter (Northern Star,1 June 1839), adding that as many intending worshippers had had to be locked out as had gained admission. But in Whitby, at least, the appeal of Chartism dimmed with its novelty. By mid September Watkins was writing bitterly to the Northern Star, ‘the working men of Whitby are very backward in their own interests, and forward in the interests of their foes. The association here is likely to be suspended for want of support’ (Northern Star 14 Sept 1839).

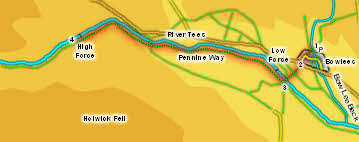

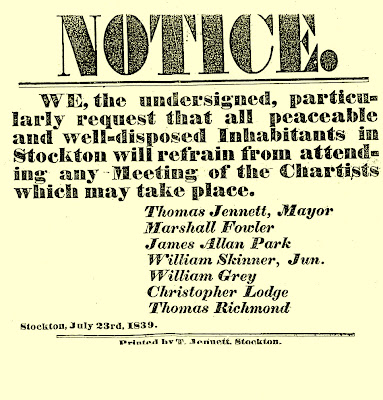

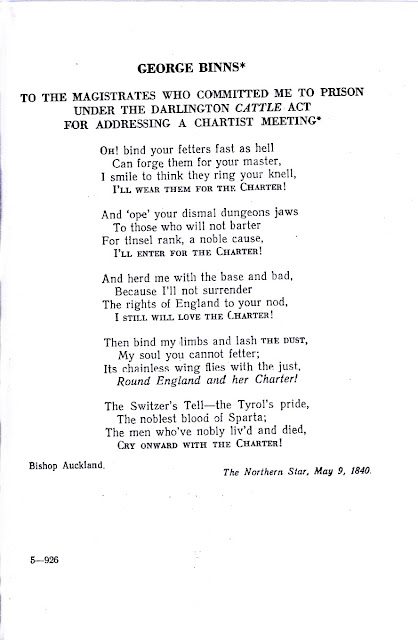

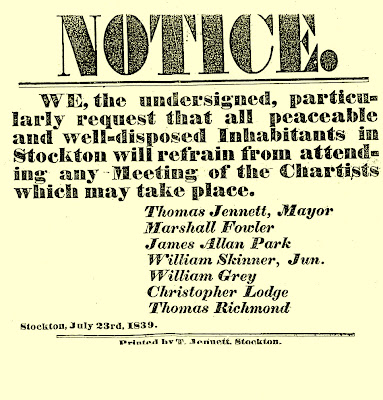

Instead, Watkins turned his attention to Teesside. In September 1839 he was arrested for a speech at Stockton, in which he called on his audience to fight for the Charter ‘like heroes [and] die for it like martyrs‘. The industrial north had been profoundly shaken by the Chartist movement which, in August, had threatened a general strike to secure the Charter. In Stockton, troops had been drafted to the town, there had been numerous arrests and, perhaps most significantly, a large body of special constables had been sworn in and organised into a paramilitary force. ‘The fact is‘, Watkins observed to his friend the Whitby-born marine painter George Chambers, ‘the Stockton Magistrates . . . were in a panic and violently prejudiced against all chartists‘ (letter, 1 April 1840, quoted in Life and Career of George Chambers, p. 147). The incident sealed Watkins’ reputation and was extensively reported and discussed in the Chartist press. On his acquittal he entered into a public correspondence with Lord Normanby, the Home Secretary, demanding his intervention to restore to Watkins a pocket book and 50 copies of his Five Cardinal Points of the People’s Charter, taken from him by Stockton magistrates when he was arrested. It greatly helped Watkins’ public profile that Normanby, of Mulgrave Castle near Whitby, could be cast as a near neighbour and almost a social equal. Much of Watkins’ appeal to Chartist audiences rested on his presenting himself as a gentleman ‘friend of the people‘, converted by force of argument to their cause and prepared to suffer for doing so. There were several precedents for so doing, pre-eminently Feargus O’Connor, a barrister from an Irish land owning family, the ‘tried and true friend of the people‘ to whom Watkins dedicated Five Cardinal Points.

There was a strong element of self-promotion in Watkins’ political activities but his sincerity is apparent in his private correspondence. ‘You seem to wonder that I should be a chartist‘, wrote Watkins to Chambers in January 1840, ‘but if you were in the north we would soon teach you to be one too. Is it not natural that that men who do their best to deserve success, and yet find all their efforts frustrated by a cursed system that rewards the undeserving alone – is it not reasonable that such men should be discontented and desire a change? It is this that has made me a chartist’. (Life and Career of George Chambers, pp. 146-47). The difficulties Chambers was experiencing in gaining the recognition Watkins believed he deserved confirmed his Chartist principles: he made a similar point in his account of the business failure of his friend Myers, which he linked directly to his death: ‘the bad system of Government occasioned by Toryism, is remotely the cause of all wants and woes which such men as Myers experience’ (Memoirs, p.115)

There was a strong element of self-promotion in Watkins’ political activities but his sincerity is apparent in his private correspondence. ‘You seem to wonder that I should be a chartist‘, wrote Watkins to Chambers in January 1840, ‘but if you were in the north we would soon teach you to be one too. Is it not natural that that men who do their best to deserve success, and yet find all their efforts frustrated by a cursed system that rewards the undeserving alone – is it not reasonable that such men should be discontented and desire a change? It is this that has made me a chartist’. (Life and Career of George Chambers, pp. 146-47). The difficulties Chambers was experiencing in gaining the recognition Watkins believed he deserved confirmed his Chartist principles: he made a similar point in his account of the business failure of his friend Myers, which he linked directly to his death: ‘the bad system of Government occasioned by Toryism, is remotely the cause of all wants and woes which such men as Myers experience’ (Memoirs, p.115)

Watkins systematically set about establishing himself as a writer in the Northern Star, the principal Chartist newspaper, owned by Feargus O’Connor. At this point in its history it was the most influential of any British paper, comfortably outselling The Times, and read aloud in political clubs, pubs and workplaces throughout the country. He contributed almost weekly to the paper from March 1840, mainly in his name but also using the pseudonyms ‘Junius Rusticus‘ and ‘Chartius‘. He was probably also responsible for the paper’s regular ‘Chartist Shakespeare‘ feature, in which extracts from the Bard were accompanied by a commentary extolling the democratic credentials of their author. His imprisonment, despite its brevity, was the subject of a five-part ‘Narrative‘ (4, 18 and 25 April, 2 and 9 May 1840 – this also appeared in the principal north-east radical paper Northern Liberator.) Readers of the paper were also treated to poetic ‘Lines written in prison‘ (25 April 1840). Watkins continued to extol his own distinctive brand of ‘Scriptural Chartism‘, with four articles of that name (12 and 19 Sept, and 3 October 1840, 13 Feb. 1841) and a poem, inelegantly titled ‘The gentry of Whitby intend to cure all the sin and misery they cause in the town by building a new church’ (24 Oct 1840). He also took up the temperance cause, whose relevance to Chartism he had extolled in Five Cardinal Points, publishing his first piece on the subject in Northern Star in January 1841. Watkins was among the 68 original signatories of an address on the subject appearing in the English Chartist Circular two months later. (This was Watkins last appearance in the Chartist press from a Yorkshire address.) This was an epoch-forming document in Chartism, since it publicly promoted a policy for Chartism that did not meet with the approval of Feargus O’Connor. Many Chartists, especially in Scotland, the Northeast and Yorkshire, argued temperance should logical be allied to Chartism. More typically, however, O’Connor believed that to espouse the temperance cause was to concede that not all men were, in their present condition, fit to exercise the vote. The appearance of this address, coinciding as it did with other initiatives to extend the reach of Chartism (into the educational field and formalised religious meetings) led to a debilitating quarrel between O’Connor and the proponents of what he condemned as a tactically devisive ‘the new move‘. On the face of it Watkins, given his temperance, religious views and espousal of a ‘moral Charter‘, seems an obvious candidate to become a ‘new mover‘: but this would be to overestimate (as many historians of the movement have done) the influence of the ‘new move‘, and also to underestimate Watkins’ ambitions to place himself at the centre of Chartism.

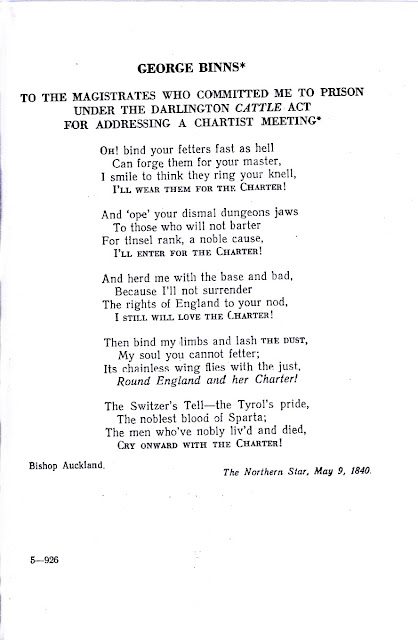

|

| Feargus O’Connor |

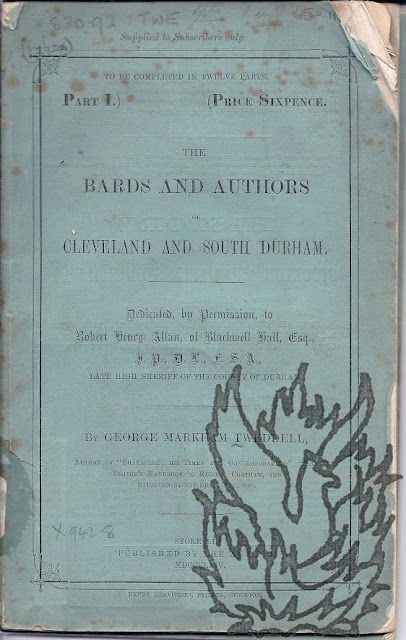

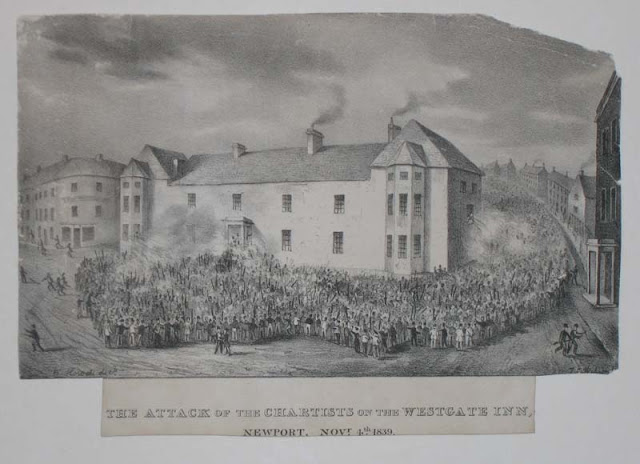

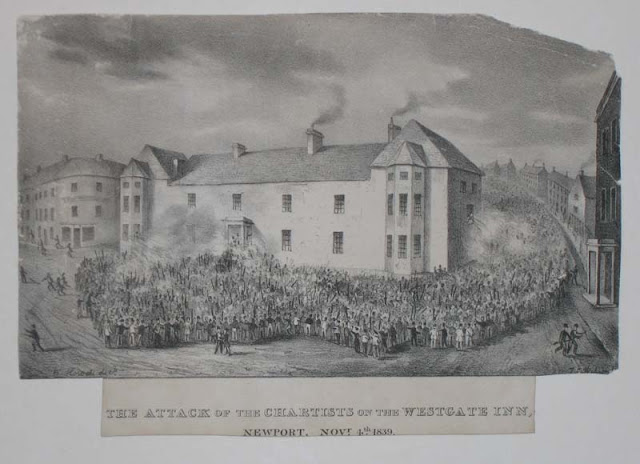

Watkins nursed strong ambitions to become one of the movement’s primary literary figures. Certainly, up to 1846 he contributed more poetry to Northern Star than any other author. His most ambitious literary effort, however, were two five act dramas in the Shakespearian mode, Wat Tyler, or the Poll Tax Rebellion: An Historical Play (1839?) and John Frost, A Political Play. About the first little is known and no copy appears to have survived. (Eds Note – in Watkins includes a letter from Ebenezer Elliott criticising it constructively in Watkin’s Life, Letters and Poems of Ebenezer Elliot the book downloadable above). Substantial extracts from the second appeared in Northern Star and the play was published in full from Watkins’ new London address in Chadwell St, Islington, in April 1841. Watkins took as his subject the Chartist rising of January 1840 in Newport, South Wales. Among its leaders was a former mayor of the borough, John Frost, who was transported to Australia for his part in the affair. For dramatic effect Watkins has Frost’s wife oppose Chartism and Henry Vincent, a leading figure in the movement and signatory to the original People’s Charter, fall in love with one of Frost’s daughters. As Kovalev, the first literary critic to consider Chartist literature observed, Watkins’ verse is predominantly imitative but he counted the play as one of ‘the two best examples‘ of Chartist literature in its earliest phase. (p. 8, translation p. 62). There are passages of real anger and bitterness in the drama, in which Watkins articulates sentiments that came as close to openly espousing revolution as any Chartist in print at this time. Eulogising George Shell, an eighteen-year old who had been shot dead by troops during the Newport rising, Watkins opines:

All foes are conquered when we conquer fear,

As did bold Shell, who braved a bloody bier.

To gain his rights he took the manliest course-

The plain straightforward argument of force!

Vengeance is now our cry. Remember Shell!

We’ll live like him – at least we’ll die as well.

The only production of John Frost appears to have been at Nottingham (see The Times 17 Feb 1844). Ostensibly this is surprising, given the popularity of John Frost and Chartism’s nation-wide campaign to have him as his fellow insurgents pardoned and brought back from Australia. The tone of Watkins’ language perhaps provides one clue as to why the author’s fellow Chartists were reluctant to venture on performance (and similarly why London’s leading radical publishers declined to publish it). Another factor, however, was probably Watkins’ deteriorating relationships with key figures in the movement which followed on his moving to London in March 1841.

The only production of John Frost appears to have been at Nottingham (see The Times 17 Feb 1844). Ostensibly this is surprising, given the popularity of John Frost and Chartism’s nation-wide campaign to have him as his fellow insurgents pardoned and brought back from Australia. The tone of Watkins’ language perhaps provides one clue as to why the author’s fellow Chartists were reluctant to venture on performance (and similarly why London’s leading radical publishers declined to publish it). Another factor, however, was probably Watkins’ deteriorating relationships with key figures in the movement which followed on his moving to London in March 1841.

Watkins had been a large fish in the small pool of Whitby Chartism. Within the broader waters of Teesside he had milked his brief imprisonment to the maximum advantage and this in turn earnt him a national reputation. Although he subsequently claimed his reason for moving to London was solely to assist Myers’ widow settle her late husband’s affairs, there seems little doubt that Watkins intended to establish himself as a professional writer and lecturer in London in the Chartist cause. In proportion to its size, however, London in the early 1840s was not a strong centre for Chartist activity. Moreover, there was no shortage of more-plausible martyrs than Watkins to the Chartist cause in the capital, some with radical political careers stretching back to the French Revolution, many of whom had endured substantial periods of imprisonment for their beliefs. Yet in less than a month of his arrival there, Watkins sallied into print attacking the apathy of London to Chartism and also the ineffectiveness of Chartists there (Northern Star 3 April 1841). He exempted from his charges William Lovett, who had drawn up the People’s Charter itself, and the radical publishers Henry Hetherington and Edmund Cleave, but this did not last. Neither Hetherington nor Cleave would publish John Frost, and Watkins soon became disenchanted with Lovett because of the latter’s central role in ‘the new move‘. Watkins violently opposed Lovett’s call for a moderate, gradualist strategy of educational and moral improvement rather than direct confrontation and dismissed him and his associates as ‘the backward move‘ (Northern Star 1 May 1841). In doing so he effectively cut himself off from the most influential and well-organised element within London Chartism and he did so in terms that could hardly permit any future reconciliation. Many Chartists remained loyal to O’Connor, believing that for all his bluster he alone could mobilise a national mass movement for the Charter. As Watkins put it: ‘To injure O’Connor is to injure the people; he is identified with them‘ (Northern Star 1 May 1841, cf. 11 Sept 1841). But Watkins also went much further, as Lovett himself recalled:

‘Among the most prominent of our assailants in London was a Mr J.Watkins, a person of some talent . . . who preached and published a sermon to show the justice of assassinating us. An extract from this very popular discourse For it was preached many times in different parts of London) will serve to convey its spirit: . . . “shall traitors to the people – the worst of traitors – be tenderly dealt with, nay courted, caressed? No, let them be denounced and renounced to face the guillotine. . . . We are in a warfare, and must have martial law- short shrift, and a sharp cord”.’ (Life and Struggles, p 251)

The language Watkins chose was not merely gratuitously violent; it clearly associated him with those Chartists who espoused the principles of the French Revolution and did not blush even at the excesses of Robespierre and the Terror. Unfortunately for Watkins, he never seems to have noticed that O’Connor was not among this faction, yet his career both in politics and as an author now hinged totally on his support for the Chartist leader. ‘I regarded him as a personification of the Cause; nay, more, I identified him with it‘. About this time Watkins made what he described as ‘a romantic pilgrimage‘ to see O’Connor in gaol at York, ‘as to the shrine of a martyred patriot‘ (John Watkins to the People, in answer to Feargus O’Connor, 1844, p. 4).

Soon after he had arrived in London, Watkins set up a bookselling business, ‘a Chartist depot for the vend of true Chartism’ near Temple Bar at 9 Bell Yard, Fleet Street. It was from here in the late spring of 1841 that he published his Life and Career of George Chambers, ‘a Chartist book’ as he described it (Northern Star 5 June 1841). Watkins’ aspirations, however, extended far beyond simply being a radical author and publisher. He hoped to exploit the breakdown in relations between O’Connor and Lovett’e circle to establish himself as the leading radical bookseller and newsvendor in the capital, hoping that the main London agency for the Northern Star, held by Cleave, would be transferred to him. O’Connor and Cleave, however, were too shrewd businessmen to part company on a point of political principle. Watkins might have displaced Cleave had his business assumed a scale to rival him: but instead Watkins had to rely heavily on credit from the Northern Star office and ran up a debt which, according to OC, had still not been repaid four years later.

He did, though, soon establish a reputation as a combative anti-Lovettite speaker and in August 1841 a meeting of the capital’s Chartist delegates (Lovett and his supporters having effectively withdrawn from all involvement in the movement) appointed him their full-time paid lecturer for the London region (Northern Star 21 August 1841). His lectures took the form of highly rhetorical addresses and were the basis of two long series of articles in the Star, ‘Watkins’ Legacy to the Chartists’ which appeared virtually weekly from 9 April 1842, and political sermons which appeared intermittently from the summer of the same year. Watkins was paid for this work, although the paper was forced to deny (24 Sept 1842) rumours that he received as much as £1 per week for his contributions

Watkins’ greatest impact was made with his Address to the Women of England, which first appeared in the English Chartist Circular (1/13, April 1841). This very full statement of the prevalent male Chartist view of gender relations was at once both idealised and sexist. Only a man committed to Chartism was worthy of a woman’s love. Her natural sphere was the home, not the world of work outside it, creating a cottage of contentment wherein the husband would find solace and refreshment from the rigours of earning a wage to support his family. Relatively few Chartists were prepared to concede that women as well as men should receive the right to vote. Watkins’ view was that the vote should be given to single adult women but not to any wife, for they and their husband were one. (In Five Cardinal Points he had argued that wives were their husband’s property.) Although he was attacked by female Chartists for being condescending (English Chartist Circular 1/16, article by Sophia from Birmingham), Watkins’ address was highly influential and it was soon after reprinted in pamphlet form. It anticipated both the rhetoric and sentiment of later statements on gender relations, made by O’Connor when he was promoting the Chartist Land Plan. A clear measure of the esteem in which it was held came the following year, when Sheffield Chartists collected publications to send to the Irish Universal Suffrage Association (Chartism was weak in Ireland and how to establish it there was a constant source of concern to the movement’s British supporters). They chose to send 250 copies each of pamphlets entitled What is a Chartist? and Hints about the Army, but a thousand of Watkins’ Address to the Women of England.

‘Born the heir of class distinctions, I nevertheless cast off all un-won privileges and flung myself into the ranks to fight my way up with the people‘, Watkins declared in an advertisement for his bookselling business in Northern Star 5 June 1841. The extent to which he was accepted in London radicalism (outside Lovett’s circle) is apparent in his election as secretary of the O’Brien Press Committee, formed by admirers of the Chartist intellectual James Bronterre O’Brien during the latter’s imprisonment in Lancaster Gaol (1841-42) with the aim of launching a newspaper for him to edit on his release. The extent of Watkins’ immersion in specifically working-class politics is apparent in his marriage to the daughter of a London stonemason, which took place in late 1841 or early 1842. The couple set up home at 20 Upper Marsh, Lambeth (where they lodged with the veteran Unstamped Press agent John Reeve) and a daughter was born very soon afterwards. It is likely Watkins met his wife through his political work, for he both wrote on strike action by the masons (Northern Star 29 January, 17 and 24 September 1842) and lectured to branches of their trade union, to whom he also donated money earnt from his writing (Northern Star 9 July and 17 Dec 1842).

In April 1842 Watkins was sufficiently ill for him both to announce he was returning to north-east Yorkshire for his health and, somewhat melodramatically, to predict his imminent death. However, the return of the prodigal never took place. His health partially recovered, but he was also ‘cast out, even by his own parents, for his attachment to our principles’. The latter statement is taken from an appeal made by a testimonial committee in his honour in July 1842. The committee was made up of stalwart City of London Chartists, among them Thomas Salmon who was to be involved in the plot among London Chartists to foment a rising in the capital in 1848. Feargus O’Connor headed subscriptions with the sum of ten shillings. The appeal was prompted by Watkins’ continued ill health (exactly with what is unclear), which in turn prompted him to plan a provincial lecture tour that would remove him from London.

It is a reflection of Watkins’ national standing that in planning this tour he received invitations to speak from Chartist branches not only in west and north Yorkshire, but also Bristol, Hertfordshire, Lancashire, Nottingham, Suffolk and Wales. However, it is a reflection of a certain political maladroitness that he turned all invitations down as soon as his health was restored. The death of his father also occasioned other acts of similar maladroitness. First there was a poem, ‘Lines on the death of my father’ in which the author compared their relationship to that of King Lear and Cordelia; then came the decision to lease The Manor House, Battersea, an address he emblazoned on items appearing in Northern Star, including a letter of thanks to subscribers of testimonial. ‘My father‘, Watkins later explained, ‘had not made me equal with his other children, but he had left me enough to render me independent in future‘ (John Watkins to the People, p. 19).

About the same time Watkins launched a highly personal tirade against other Chartist publishers (‘mere traffickers in politics’) and continued to abuse the ‘new move’ (‘nothing more than a recoil back to the old move of Whig-Radicalism’). He was less happy receiving criticism, on one occasion comparing his critics to the Jews who persecuted Christ (Northern Star (5 and 12 Nov 1842). None of this helped the next stage of Watkins’ political evolution, in which he attacked O’Connor’s leadership of Chartism. This had begun tentatively with a pronouncement that a temporary executive appointed to manage the National Charter Association (NCA) was undemocratic (Northern Star 12 Nov 1842). Early the following year Watkins ‘earnestly entreated’ O’Connor ‘not to give pain to the Chartists by calling them “his party”‘ and strongly criticised O’Connorite members of the NCA executive, even terming Peter M’Douall ‘a swindler’ (28 Jan 1843). That the accounts of the NCA at this time were in disarray was never disputed. O’Connor, though, was swift to exempt the executive of any personal dishonesty and atypically (for his policy as its owner at this time was not to interfere in editorial decisions) criticised the editor of the Northern Star for publishing Watkins’ attack. He reserved his strongest words to attack Watkins’ attitude to the Manchester Chartist John Leach, a former handloom weaver who had become a cotton factory operative until sacked for resisting wage reductions in 1839. Despite persistent poverty, Leach had repeatedly donated to Chartist funds ‘money freely given to him’ (4 February 1843). The implication was clear – Watkins (who had publicly declined a request to assist in straightening out the financial procedures of the NCA) was carping unfairly against Chartists less fortunate, economically and socially, than himself.

Watkins was very far from alone in criticising O’Connor and his closest associates but he was compromised by his earlier and exaggerated criticisms of the ‘new move’. This cut him off from the natural focus of non-O’Connorite Chartism in the capital. Henceforward he had to try and make his own way. The medium he chose was a journal, the London Chartist Monthly Magazine, the first issue of which appeared under his editorship on 1 June 1843. Each issue was to include a portrait (a device used to considerable effect in building up a subscription base to Northern Star) and a range of essays, fiction and historical material. 1843, however, was not a propitious time to launch a new chartist journal. The rejection of a monster petition (comprising 3.3 million signatures) to Parliament in May 1842, and a widespread but ultimately futile wave of strikes (with which Chartism was integrally linked) the following summer, had taken their toll on Chartist morale. The monthly magazine format was also a relatively untried formula in radical publishing. It did not survive beyond four issues.

Watkins therefore had to look elsewhere to expound his views. He strongly supported William Hill, a nonconformist minister from Hull and the former editor of Northern Star, who had made a very public exit from the paper over his differences with its proprietor. In another ephemeral journal of the period, Hill’s The Lifeboat, Watkins attacked O’Connor as ‘the chief stumbling-block in our way to the Charter’, He added with typical verve and venom that the movement’s leader ‘retreats under cover of the N——- S—, where, like the scuttle fish, he hides himself under a cloud of ink’ (Lifeboat 16 Dec 1843). O’Connor described the two men as his ‘most virulent’ accusers (Northern Star 24 Feb 1844), but Watkins soon eclipsed Hill with the publication first of The Impeachment of Feargus O’Connor (1844?) and then John Watkins to the People, the title page of which was adorned with a quotation from Macbeth, ‘This tyrant, whose sole name blisters our tongue, was once thought honest’.

John Watkins to the People is essentially autobiographical (though curiously it suppresses details of his marriage – it is possible that his wife may already have died). The veracity of all that it contains is doubtful but it provides useful contextual information about London Chartism and the relationship between O’Connor and prominent radicals there. Watkins’ interpretation of the ‘new move’ was that it was got up by London radicals in an attempt to seize the initiative back from O’Connor in the Chartist movement. Watkins is frank about his own ambitions to profit from the dispute between them and provides a detailed account of how and why he had been so loyal to O’Connor.

Watkins followed the pamphlet with a steady stream of articles denouncing the Chartist leadership in general, and O’Connor especially, in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper. These mostly appeared over the pseudonyms of “Lictor” or “An Old Chartist“, but he was also responsible for a series of anonymous addresses to Thomas Slingsby Duncombe, the radical MP for Finsbury and O’Connor’s closest political ally. Watkins, however, was now on difficult ground. He had alienated every London Chartist of any significance whilst the columns of Northern Star were denied to him. Watkins discomfort must have increased when publication of Northern Star was shifted from Leeds to London in December 1844. O’Connor meanwhile used the Star to quote samples from Watkins’ earlier “sack of adulation” and detail “his mean, unprincipled, and scandalous attempt to build up for himself a trade, as publisher and bookseller, on the ruin of old established pressmen” (Northern Star 18 Jan and 1 Feb 1845). It was now very difficult for Watkins to function in London Chartism at all, or to find a publisher for his work. There was further, isolated foray into publishing in 1847, titled Runnymede or Magna Charta: A Historical Tragedy. “Sixty-four pages of nonsense in imitation of blank verse . . . it will prove a valuable opiate, should any one require artificial aid in courting the embraces of sleep” claimed the Northern Star reviewer. Watkins appearances at political meetings were now sporadic. Apparently the last of them (attacking O’Brien) was in early April 1848 (Northern Star 15 April 1848): he seems otherwise to have taken no part in the momentous events of London Chartism that year.

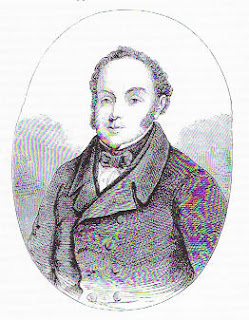

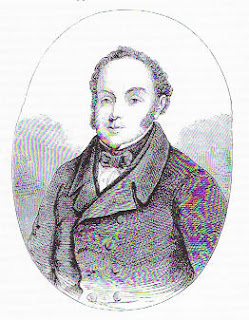

|

| Ebenezer Elliott |

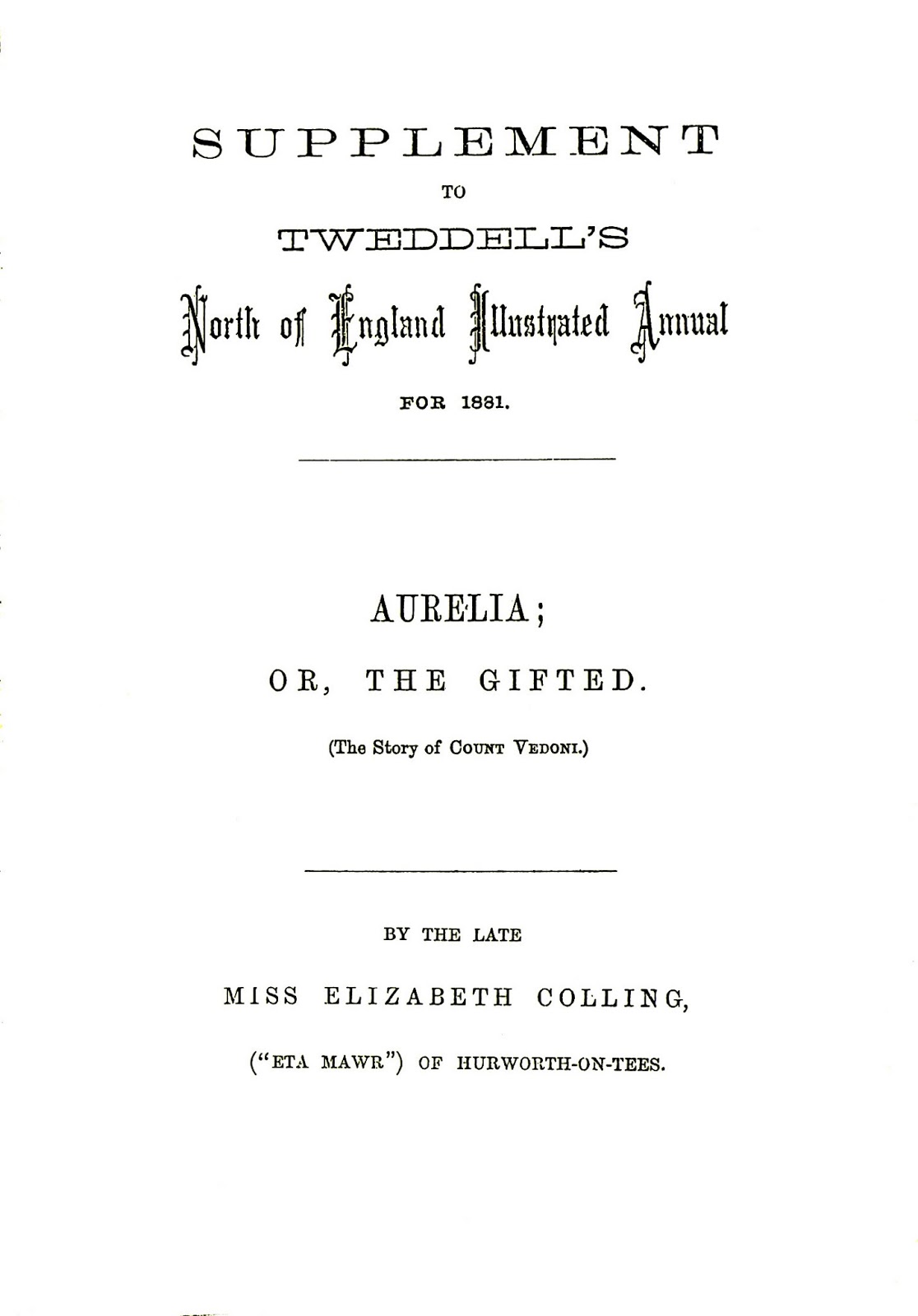

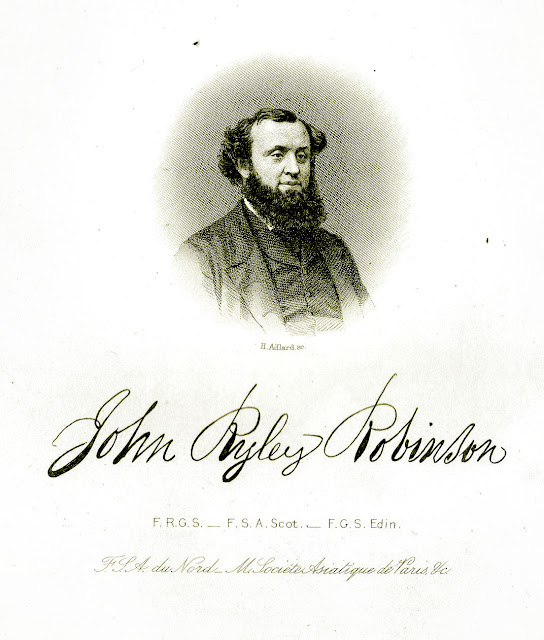

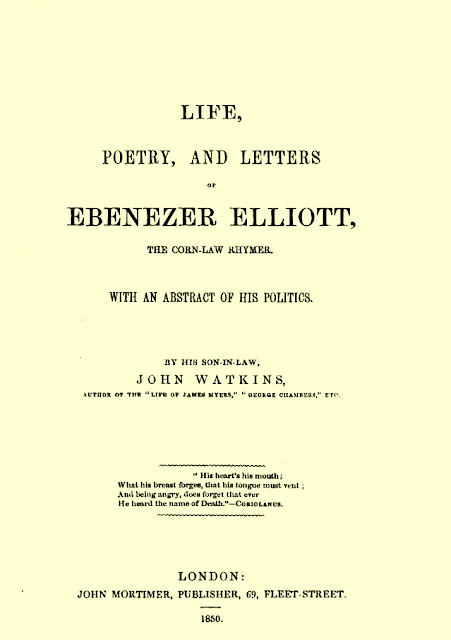

Watkins continued to move in radical and literary circles but, in keeping with his status as a man of independent means, he moved nearer the political centre. On 17 Nov 1849 he married the daughter of Ebenezer Elliott, a Sheffield businessman who had been an early supporter of moderate Chartism but had broken from the movement over its stance on the Corn Laws. As the self-styled “Corn-Law Rhymer“, Elliott was a popular and influential voice in the campaign to repeal the Corn Laws, legislation that was finally forced through parliament by the Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel in 1846. Watkins and Mary Elliott married a few days before her father’s death in 1849. The following year he compiled and published The Life, Poetry and Letters of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn-Law Rhymer, and dedicated it to the Tory Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, who had recently died. The couple made their home at Grove Court, Clapham Rise, from which address, describing himself as “John Watkins, Gentleman” he made a will in August 1850. He died there in January 1858. His death seems to have gone unnoticed on Teesside and in Whitby: for example, the usually reliable George Smales, in his Whitby Authors and their Publications (1867), failed to give any date for it.

John Watkins was hardly an appealing figure. An exaggerated taste for controversy and self-agrandisement, not to mention intolerance of those with whom he disagreed, arguably robbed Chartism of a capable and even gifted writer. William Lovett, whom he assailed unmercifully, freely conceded Watkins was “a person of some talent“. Bronterre O’Brien, another Chartist leader lashed by his pen, lamented his inability to “forget SELF when he is writing” (quoted in Northern Star 28 June 1845). Reviewing his life it is hard to dissent from the judgement of his Whitby friend James Myers who, at the time Watkins had entered into a “foolish controversy” with George Young, the founder of the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society, spoke to him frankly of his “thorough want of control over thy impetuous and childish caprices, which forms one of thy great characteristics‘ (quoted in Smales, Whitby Authors, 147). Yet Watkins’s neglect at the hands of historians of Chartism is undeserved. He was an important figure in the movement in the North Riding but more crucially he was one of the most regular and prolific contributors to the Northern Star during its period of greatest influence. Until the Chartist R.G.Gammage published his History of the Chartist Movement in 1854, Watkins was also O’Connor’s most public and stringent critic. Watkins influence on Chartism was therefore significant, though it hardly took the he craved when he embarked on his career as a Chartist in Whitby and on Teesside. Is he significant for Teesside and north-east Yorkshire? Ultimately the answer must be “not especially” – unless we use as a measure of significance the mere size of the circulation his writings whilst living in the region enjoyed through the Northern Star (around 50,000 copies a week at its peak). But Teesside was significant for John Watkins: his arrest at Stockton and the short imprisonment that followed made his national reputation within one of the greatest mass movements in British political history.

Bibliography of John Watkins’ Work

Watkins’ contributions to local journals such as Whitby Repository and Whitby Magazine are not included here. However, this list does give all Watkins’ book-length and pamphlet publications, the most complete collection of which is in the Library of the Whitby Literary & Philosphical Society. Also listed are all Watkins’ Chartist poems and political journalism that I have been able to trace (including some pieces written under a pseudonym). Those that appear in Northern Star are listed separately.

The Stranger’s Guide through Whitby and the Vicinity (Whitby: R.Kirby, 1828; reprinted 1841, 1849 and 1850).

Scarborough Tales, by A Visitant, (Whitby: R.Horne, 1830)

Remains of James Myers, of Whitby, with an Account of his Life (Whitby: R.Horne, 1830)

Contributions to the Whitby Repository, 1833 and Whitby Magazine

A Letter to the Lawyers (Beverley, W.B.Johnson, 1834)

The Emigrants: A Tale of the Times (Whitby: Horne & Richardson, 1835

Lay Sermons, (Whitby, Horne & Richardson, 18350

Captain Cook, the Circumnavigator (Whitby, W.Forth, 1837)

Memoir of Chambers, the Marine Artist (Whitby, W.Forth, 1837)

A Letter to the Inhabitants of Whitby, particularly addressed to the middle classes, on the decline of the town, (Whitby, W.Forth, 1838)

A Second Letter to the Inhabitants of Whitby, calling upon them to Release the Town from the Tyranny of Toryism (Whitby, W.Forth, 1838)

A Third Letter to the Inhabitants of Whitby; being the conclusion of the whole matter, By a Friend of the People (Whitby, W.Forth, 1838)

Memoir of Joseph Bower, Whitby, W.Forth, 1838

Memoirs of the Talents, Virtues and Misfortunes of James Myers (Whitby, R.Kirby, 1839)

Padfoot: A Satire. By Nemesis (Stockton, Appleton, 1839)

The Five Cardinal Points of the Charter Separately Explained and Advocated, (Whitby, W.Forth, 1839)

Narrative of his imprisonment, Northern Liberator, 25 April – 15 May 1840, inc.

Wat Tyler, or the Poll Tax Rebellion: An Historical Play in Five Acts, (London: Salisbury & Bateman, [1839?])

Memoir of James Myers, (Whitby: R.Kirby, 1839)

Hymns to be used at the Working Men’s Chapel, Whitby, (Whitby, W.Forth, [?1839])

John Frost, a Play (London, Watkins, 1841)

Life and Career of George Chambers (London, Watkins, 1841)

Address to the Women of England, English Chartist Circular vol. 1, no 13 (April 1841) p.50.

Address to the Women of England (?1842)

London Chartist Monthly Magazine, 1 June 1843 -? – there are no surviving copies, but for some reviews see English Chartist Circular no. 135 and Northern Star 8 April and 20 May 1843.

Letter to the editor, Lifeboat 16 Dec 1843.

Impeachment of Feargus O’Connor (London, Watkins, 1843)

John Watkins to the People, in answer to Feargus O’Connor. Comprising the Whole Chartist Life of John Watkins, (London, Watkins, 1844)

Runnymede or Magna Charta: A Historical Tragedy (1847 – no surviving copy but for a review see Northern Star Oct 1847)

Life, poetry and letters of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn-Law Rhymer (London: John Mortimer 1850)

Contributions to Northern Star

‘Swarthone’ 28 March 1840

‘Narrative of the imprisonment of John Watkins’, 4, 18 and 25 April, 2 and 9 May 1840

‘Lines written in prison’, 25 April 1840

Letters to lord Normanby, 20 June and 4, 11 and 25 July 1840

Lines on Mulgrave Castle, 1 August 1840

Letter to McDouall, 5 Sept 1840

Letter to Normanby (on the Norman Yoke) 12 Sept 1840

Scriptural Chartism, 12 and 19 Sept, and 3 October 1840, 13 Feb. 1841.

Poems, 12, 19 and 26 Sept 1840

Lines on Shell, Killed at Newport, 26 Sept 1840 (Kovalev)

Letter to the Middle Classes, 26 Sept 1840

Poem 3 Oct 1840

Sonnets to Feargus O’Connor and The Yorkshire Hills, 17 Oct 1840

Account of visiting O’Connor in York Castle, 17 Oct 1840

‘The gentry of Whitby intend to cure all the sin and misery they cause in the town by building a new church’ [poem], 24 Oct 1840

‘Junius Rusticus’, Letter to Lord Normanby, 24 Oct. 1840

Other ‘Junius Rusticus’ letters, 7 Nov, 5, 12 and 26 Dec 1840, 16 Jan (to Queen Victoria) and 30 Jan (to Lord Palmerston) 1841

Chartism: A Fragment, 5 Dec 1840

Extracts from John Frost, 5 Dec 1840 and 2 Jan 1841

Chartism and teetotalism 23 Jan 1841

Letter 20 Feb 1841

Attack on the apathy of London to the Chartist cause, 3 April 1841

‘The backward move’, 1 May 1841

The Corn Law Question, 22 and 29 May 1841

Address (in the form of an advertisement for his new shop in London, 5 June 1841

Letter to the editor, 31 July 1841

‘Junius Rusticus’ letter and poem, ‘London, thou art a wilderness’ by ‘A Country Chartist’, 28 August 1841

‘The Corn Laws and Emigration’, 1 and 8 Jan 1842

Poem about the stonemasons’ strike, 29 January 1842

Letter 2 April 1842

Sonnet, 9 April 1842

‘Watkins’ Legacy to the Chartists’, 9 April 1842 and subsequent issues

Sonnet, 25 April 1842

Sonnet to Sir John Roubiliac, 7 May 1842

‘To my infant daughter’, 25 June 1842

Chartist lines for recitation, 3 Sept 1842

‘Nicholas Postgate, the Old Catholic Priest’ by ‘Chartius’, 10 Sept 1842

‘The late strike, its cause and effect’, 17 and 24 September 1842

‘Chartist Song’ and ‘The Emigrants’ by ‘Chartius’, 1 Oct 1842

‘Lines on the death of my father’, 15 Oct 1842

Letter to subscribers of his testimonial committee, 5 and 12 Nov 1842

‘The Charter – An Ode, 12 Nov 1842

Letter, 12 Nov 1842

‘Letter to Joseph Sturge’, 3 Dec 1842

Poem, ‘The System’, 7 January 1843

Letters attacking the National Charter Association executive, 28 Jan 1843

‘Man Worship’, 4 and 11 Feb. 1843

He who is not for us is against us, 11 Feb 1843

Letter, on land reform, 18 Feb 1843

Attack on O’Connor, 1 Feb 1845

Sources for John Watkins’ Life

(1) Unpublished MSS: The National Archives, Kew, London, Probate Inventories, PROB 11/2263/228, John Watkins.

(2) Published material: NS 1 June, 5 Oct 1839, 27 Mar, 3 Apr 1841; English Chartist Circular 1/16 [May 1841]; NS 5 June, 14 and 21 Aug, 18 Sep 1841, 2 Apr, 4 and 11 June, 2 and 9 July, 13 Aug, 10 and 24 Sep 1842, 11 Feb 8 Apr and 20 May, 3 and 24 June, 8 July 1843; The Times 17 Feb 1844; NS 17 and 24 Feb, 2 Mar 1844, 18 Jan and 1 Feb, 3 May and 25 June 1845; National Reformer 19 Dec 1846; NS 2 Oct 1847; G. Smales, Whitby Authors and their Publications, 867-1867 (Whitby, 1867); W. Lovett, The Life and Struggles of William Lovett in His Pursuit of Bread, Knowledge and Freedom (London, 1876); R. G. Gammage, History of the Chartist Movement, 1837-54 (1854; 2nd edn 1894, repr. 1969 and 2006); D. Williams, John Frost: A Study in Chartism (Cardiff, 1939), 297-98; Y. V. Kolavev, An Anthology of Chartist Literature (Moscow, 1956) – translation of preface in L. M. Munby, The Luddites and Other Essays (London, 1971); A. Plummer, Bronterre: A Political Biography of Bronterre O’Brien, 1804-64 (London, 1971); B. Harrison, ‘Teetotal Chartism’, History 193 (June 1973) *; D. J. V.Jones, Chartism and the Chartists (London, 1975); R. P. Hastings, ‘Chartism in South Durham and the North Riding of Yorkshire’, Durham County Local History Society Bulletin 22 (Nov 1978), 7-17; R. P. Hastings, Essays in North Riding History, 1780-1850 (Northallerton, 1981); J. Epstein, The Lion of Freedom: Feargus O’Connor and the Chartist Movement, 1832-42 (London, 1982); D. Goodway, London Chartism, 1838-48 (Cambridge, 1982); M. Chase, ‘Chartism, 1838-58: Responses in Two Teesside Towns’, Northern History 24 (1988) *; J. Schwarzkopf, Women in the Chartist Movement (London, 1991); S. Roberts, ‘Who Wrote to the Northern Star?’, in O.Ashton et al, The Duty of Discontent: Essays for Dorothy Thompson (London, 1995), 55-70; A. Russett, George Chambers, 1803-1840: His Life and Work . . . with Extracts from the 1841 Biography by John Watkins (Woodbridge, 1996); R. P. Hastings, Chartism in the North Riding of Yorkshire and South Durham, 1838-48 (York, 2004); M. Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester, 2007).

* = reprinted in S. Roberts (ed.), The People’s Charter (London, 2003)

In answer to the comment below

“You mention that Watkins was a playwright. Was he the author of “Griselda”, “Oliver Cromwell, the Protector : an historical tragedy” ? (you don’t list any plays among the published materials).

Thanks.” I found this from the book Chartist Drama – edited by Gregory Vargo. In reference to Watkins.

.jpg)

.jpg)