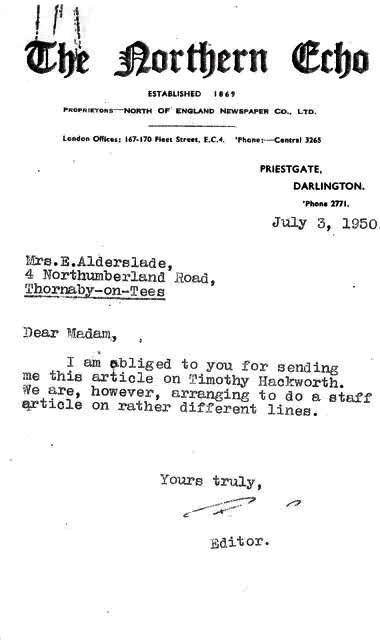

This proposed article (or series of notes towards one) was submitted to The Northern Echo on July 1st 1950 by Esther Alderslade (Nee Hackworth) of Thornaby on Tees on the Centenary of Timothy Hackworth‘s death. Timothy died in 1850. The Northern Echo covered Timothy Hackworth on many occasion and interviewed the family along the way but on this occasion the article was rejected by the editor as they had planned to do a “staff article on rather different lines”. However, the article below, some of which pulls out information from Robert Young‘s book Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive, gives a useful overview of Timothy’s many achievements as a Railway engineer and a man of the community – ie New Shildon.

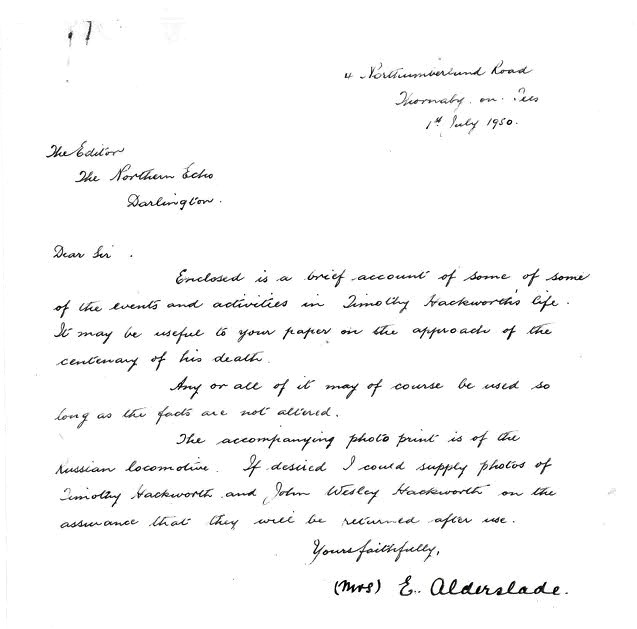

First – here is Esther’s letter and the reply from the Northern Echo –

On the approach of the Centenary of Timothy Hackworth‘s death it may be of interest to revive the memory of some of the work he accomplished.

To the question “Which was the first successful Locomotive?” the vast majority of people would answer without hesitation “George Stephenson’s Rocket“. Few people are aware that the problem of steam locomotion as a commercial proposition was solved in 1827 when the Royal George was built by Timothy Hackworth.

The promise of the Stockton and Darlington Railway which was opened with such enthusiasm in 1825 by Locomotion No 1 had not been fulfilled. Shares were falling, most shareholders wanted to sell and the company all but decided to revert to horsepower.

On Timothy Hackworth‘s undertaking to build a locomotive which would meet with requirements, the

|

| Hackworth’s Royal George 1827 had the steam Blast pipe. |

Royal George was built as a last experiment. For the sake of economy, an old boiler was used and adapted. Amongst a number of new features in this locomotive the most important was the Steam Blast Pipe which was attached for the first time. The Royal George was a great success and was the first locomotive to exceed the efficiency of horsepower, carrying coal at less than half the cost. It opened a new and successful era of the locomotive. Two Years later in 1829 George Stephenson built The Rocket which made him famous.

The origin of the Steam Blast Pipe, which was the deciding factor in making steam locomotion triumph over horses, was never disputed until Samuel Smiles wrote his book on George Stephenson. (link is to a free pdf book download) In this, with little experience, he attributed the invention to him. There is still in existence, however, an original letter written by George Stephenson to Timothy Hackworth which proves that he knew nothing of the blast pipe at the time the Royal George was built. The popularly entitled ‘blast pipe letter‘ from George Stephenson to Timothy Hackworth can now be see on this site here –

|

| Jane Hackworth Young with the ‘blast Pipe letter’ c2004 at Locomotion. |

An event in which Timothy Hackworth played prominent part was the extension of the railway to Middlesbrough and the opening of the latter as a port. It may be difficult for us to imagine Teesside without this now dominating industrial port, but in 1829 it only consisted of one house called ‘Parrington’s Farm‘, or shepherd’s hut and a large swamp. Being nearer the mouth of the river, however, it was better situated than the older town of Stockton, where the river narrows to take large ships and the coal export trade was growing.

|

| Hackworth’s Coal Staithes, Middlesbrough 1830 |

The Railway company advertised for plans for the construction of shipping staithes, offering premiums of 150 guineas and 75 guineas for the best designs. This attracted many engineers of talent and after a patient investigation of 15 plans, the first premium was awarded to Timothy Hackworth and the second of 75 guineas to J. Cooke of Yetholm.(Scotland)

|

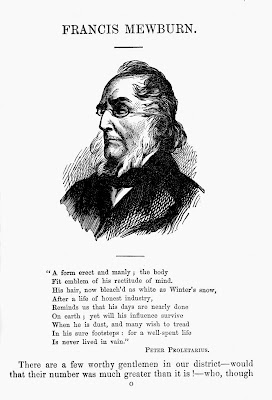

| From Bards and Authors of Cleveland – George Markham Tweddell 1872 |

In 1830, Hackworth started the construction of the Staithes on behalf of the Railway company. He made all the contracts and superintended the erection and completion of the whole in accordance with his own designs. The staithes were on original lines, excited much interest at the time, and efficiently served their purpose for many years. ‘Lip vessels‘ could be loaded one at a time. The wagons were lifted by steam power twenty feet and covered by means of a cradle from ‘sheer legs‘. There was an ingenious contrivance by which a loaded wagon in descending raised an empty one and replaced it on rails to take to a siding. 1. (For a description of the Staithes, see the longish footnote at the end of this post – by George Markham Tweddell – local poet, author , printer, publisher and people’s historian)

On December 27th 1830, the railway extension to Middlesbrough was opened and the coal Staithes were put into operation for the first time. The coal was duly shipped and the proceedings concluded with a repast served in the gallery of the Staithes where no less than 600 people were feasted under the chairmanship Francis Mewburn.

There were great demonstrations of joy with free rides, firing of guns, toasts and speeches. A medal was struck for the occasion with the Staithes on one side and the new railway suspension bridge over the Tees on the other. ed’s note (In 1980, Jane Hackworth Young launched the plaque to commemorate the Staithes and honour Timothy Hackworth.)

|

| https://www.flickr.com/photos/bolckow/5412916380/ |

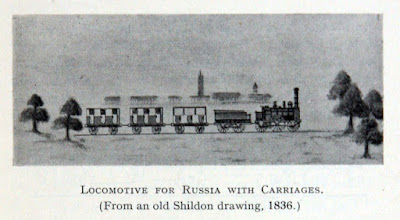

Amongst the many inventions claimed by the Russians as their owner, is the important one of the Locomotive. It may therefore be of interest to recall the story of the first one ever to run in Russia. This was designed and built at Shildon by Timothy Hackworth. The duty of introducing the locomotive into Russia devolved upon Hackworth’s son John Wesley Hackworth, then not quite 17 years old. He was a tall, well set up youth, a keen and clever engineer, absorbed in his profession and in his appearance, much older than his years.

Amongst the many inventions claimed by the Russians as their owner, is the important one of the Locomotive. It may therefore be of interest to recall the story of the first one ever to run in Russia. This was designed and built at Shildon by Timothy Hackworth. The duty of introducing the locomotive into Russia devolved upon Hackworth’s son John Wesley Hackworth, then not quite 17 years old. He was a tall, well set up youth, a keen and clever engineer, absorbed in his profession and in his appearance, much older than his years.

|

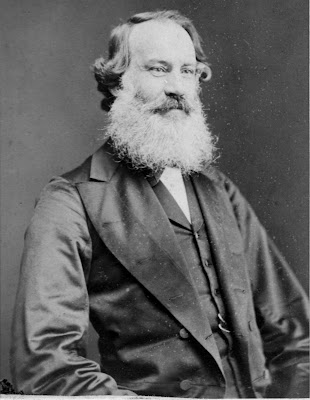

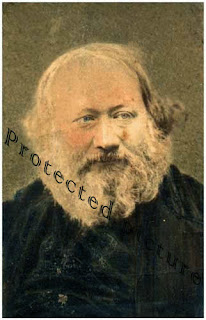

| John Wesley Hackworth |

Young Mr Hackworth, with a small staff, set off to Russia in the autumn. At that time of the year the ordinary channels of communication were closed and they had to land at an open port in the Baltic, then make the journey to St. Petersburg by sleigh in weather that was so severe that the spirit bottles broke with the frost and they had to run the gauntlet of a pack of wolves.

Hackworth’s foreman – George Thompson from Shildon deserves special mention for a smart piece of work which he carried out. When the engine had worked a few days, one of the cylinders cracked and Thompson made the arduous journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow, a distance of 600 miles, to the ordinance factory, made a pattern for the cylinder, got it cast, bored out and fitted, returned to St. Petersburgh and fixed it in the engine.

The locomotive was taken from St. Petersburgh to Tsarskoye Selo where the Imperial Summer Palace Tsar Nicholas and a distinguished company in November 1836.

was situated. It was here that the locomotive started in the presence of

John Wesley Hackworth was introduced to Tsar Nicholas who told him of a visit paid to England in 1816 before his accession to the throne, when he had witnessed with great pleasure the running of Blenkinsop‘s engines on the colliery line from Middleton to Leeds. The Tsar added some complimentary remarks regarding the new locomotive under their present inspection, saying he “could not have conceived it possible so radical a change could have been effected within twenty years.“

The engine, before being brought into public requisition had to be put through a baptismal ceremony of consecration according to the rites of the Greek church. This was done in the presence of the assembled crowd. Water was offered from a neighbouring bog or ‘stele’ in a golden censer, and sanctified by immersions of a golden cross amid the chanting of choristers and intonations of priests while a hundred tapers were held around it.

supplications that on all occasions of travel by the new mode, just being inaugurated, they might be well and safely conveyed. Then came the due administration of the ordinance by one priest bearing the Holy censer while a second, operating a huge brush and dipping in the censer dashed each wheel with the sign of the cross, with final copious showers all over the engine, of which

Mr Hackworth was granted a passport to travel anywhere he wished in Russia, where he stayed for a while introducing the railway. He returned to England wearing a beard. Of this, his family did not approve but he retained it and some years after the Russian war, beards became fashionable in England.

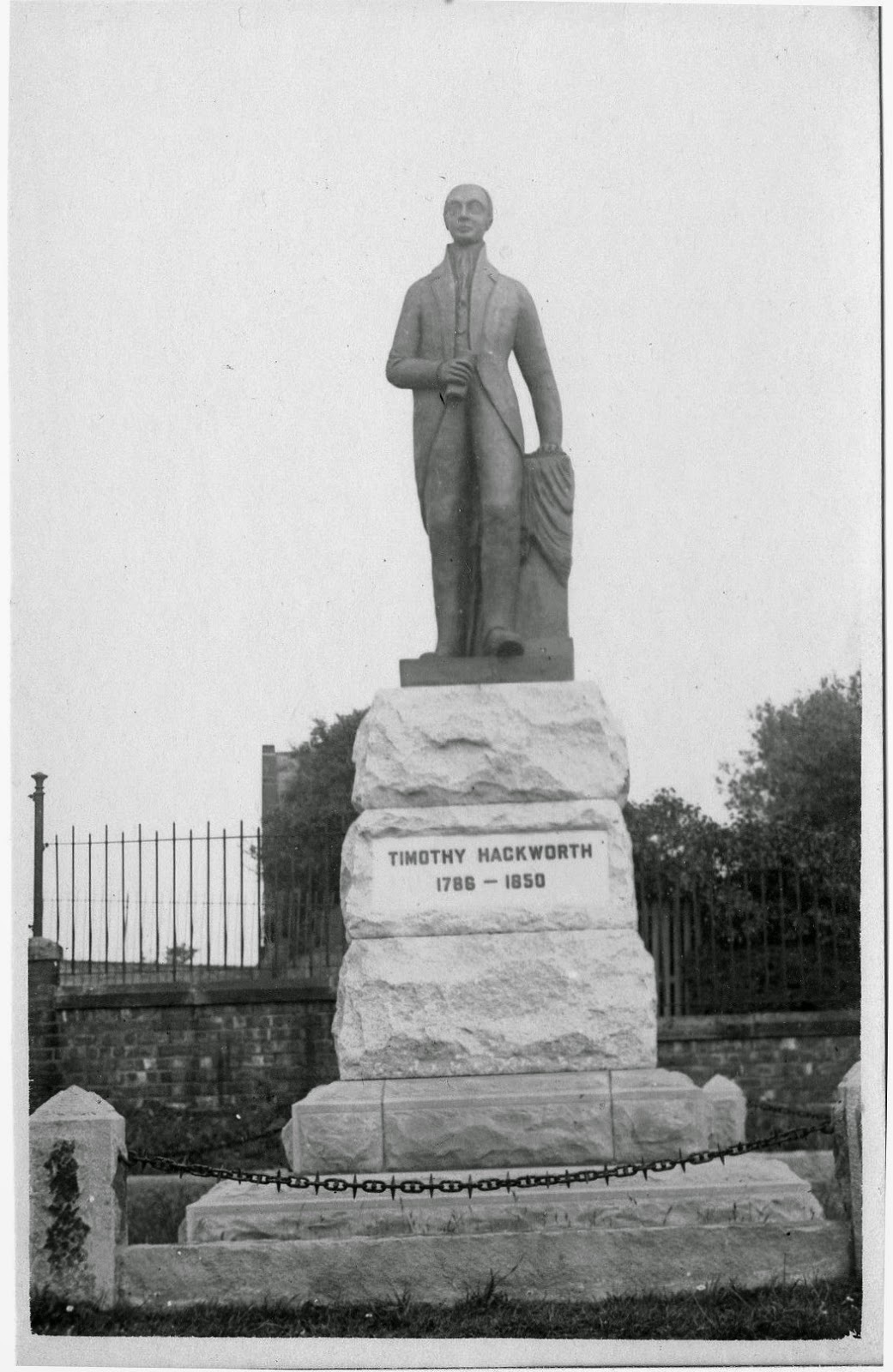

It would appear that the Russians have got their history rather mixed, and it was the Victorian beard they were responsible for not the locomotive! These achievements form only a small part of Timothy Hackworth‘s life work. he built a large number of locomotives of very varied designs and his inventions were numerous. Rarely did he use the patent office, freely giving his ideas to the world.

|

| Jane Hackworth (nee Golightly) Timothy’s wife |

Although so absorbed in mechanical pursuits he found time for other occupations. The life of the district was Timothy Hackworth as an apprentice was a passport to another job for those who chose to go further afield. He took a personal interest in all, and looked upon them not as ‘hands’ but fellow workers.

his concern, for most of the people were his employees of his own or the Railway company’ and the town of New Shildon grew up around his works. It has been said that Shildon Works was the school of the education of many of the most eminent engineers in the profession. To have been in the employ of

At first there was no place for worship in the neighbourhood so he set himself to provide one, setting aside a room in his own house for the purpose. Through his exertions Methodist chapels were eventually erected in Shildon and new Shildon.

So ardent was he that he had left the church because he could not be a lay preacher there. With both Mechanics Institute of which he

Methodists he occupied every office as a layman, and as a preacher was very popular. Local preaching was very strenuous in those days as it entailed much walking to the various villages in the circuit. He was very fond of children with whom he was a favourite and he gave much time to Sunday school work. He constructed a society class meeting which was extraordinarily successful. It grew so large it had to be divided again and again. For many years he was president of the New Shildon

was one of the founders.

When the British Association for the Advancement of Science was formed, Timothy Hackworth became a member and attended some of its meetings. His home life was very happy, with a large family and a good wife who entered wholeheartedly with all his schemes. Being very much appreciative of music, his daughters were carefully instructed in the art and he himself taught his children to dance.

|

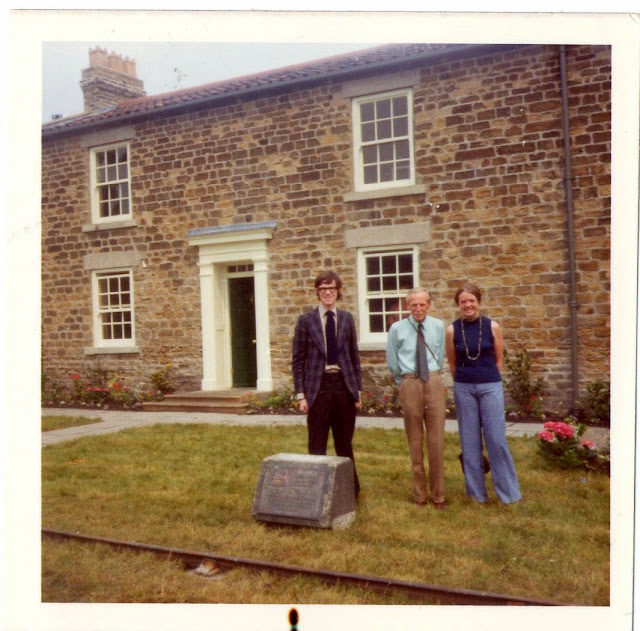

| Hackworth House, Shildon With Hackworth’s Ulick, Reg and Jane |

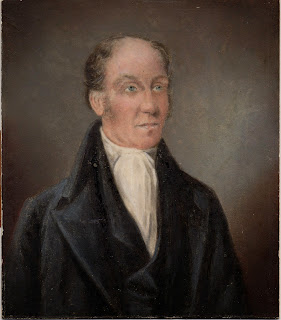

The care of the garden was another pastime which he enjoyed. His position as a pioneer in engineering John Wesley) .It was a great pleasure to show hospitality to all who came. Thus busily and happily with little person ambition for wealth and fame, passed the life of Timothy Hackworth, a benefactor of mankind who earned the respect and affection of all around him. He passed away after a short illness at the age of 64 and was buried in the churchyard of Shildon Parish Church where the whole population assembled to pay tribute for his character and also for the people of Shildon, that in this age of speed and quick forgetfulness they pause to remember one who died a hundred years ago.

brought many visitors and his interest in Methodism made his house the destination of most visiting preachers. (He was a personal friend of

Mrs Esther Alderslade (nee Hackworth) 1.7.1950

Footnote 1. From – A HISTORY MIDDLESBROUGH

From the Tweddell family archives originally published in Bulmers North Yorkshire directory 1890 and

|

| George Markham Tweddell |

described by historian Asa Briggs, as the best history of the town, when he was researching his book Victorian Cities. This is an extract from the full history which can be read here on my Tweddell Hub site.

George Markham Tweddell on the coal staithes in Middlebrough.

“The railway to Middlesbrough was opened December 20th, 1830, with a train of passengers and coal, one immense block of “black diamonds” from the Old Boy Colliery figuring conspicuously, which, when broken, was calculated to make two London chaldrons. Staiths had already been erected to load six ships at one time, and the visitors witnessed the loading of the Sunnyside, under the management of Mr. William Fallows, then in his thirty-third year, who the year previous had been appointed agent to the Stockton and Darlington Railway at Stockton, and who, in 1831, became a permanent resident of Middlesbrough, where for fifty-eight years he was a main mover in every movement for the material, mental, and moral progress of the place of his adoption. The mode of loading the vessels laying along the low-banked river was very ingenious. Each waggon of coal was run on to a cradle, then raised by steam power to the staithes, and lowered by “drops” to the decks, a labourer descending with each waggon, undoing the fastening of the bottom, and thus allowing the coals to fall at once into the ship’s hold, when he ascended with the empty waggon, which was returned to the railway with the same machinery, In the principal gallery of the staithes, covered in and adorned for the festive occasion, and lighted by portable gas – the first ever burnt in Middleshrough – a table, 134 yards long, loaded with provisions, supplied the needed bodily refreshment to nearly six hundred hungry spectators, all of whom entertained glowing hopes of the prosperity of the new venture. But none then were so very sanguine as to imagine, for one moment, that its miles of streets would ever extend far beyond the proposed new town; that it would soon become a municipal borough, with Mr. Fallows for one of its mayors and justices of the peace; that in thirty-seven years’ time it would have its own special representative in the House of Commons; and that, in the lifetime of some then present, its manufactures, both useful and artistic (its Linthorpe pottery among the latter), would become famous throughout the world.”

Hello, Trev Teasdale!

Please tell me the source of the figure published in your blog post:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-9JNSkdnBwes/VZ8HMdxJQ7I/AAAAAAAAF9E/ondVccyF1qQ/s320/Im1923TimHack-LocoRussia.jpg

You can get this image in a better resolution? Can I use it on the internet forum, a thread dedicated to the history of the Tsarskoye Selo railway?

Sincerely,

Dmitry Kudryashov.