THE JOAN HACKWORTH WEIR (Nee PARSONS) STORY

(An interview conducted by Margaret Weir and Trev Teasdel in 1995)

“An insight into the conjoining of the Parsons family and descendants of Timothy Hackworth in Stockton and Thornaby And a fascinating glimpse into the social and economic life of late 19thC / early 20th C Teesside.”

Joan was a great storyteller and these stories had been handed down through the family…

- The Parsons and the Hackworths

- Migration from Staffordshire to Teesside in 19thC

- A Stockton Story – Castlegate and Thistle Green, Pubs and Property

- Making a Mint of Cherry Fair Day

- A Redcar Story – Surviving Poverty

- Sugar Mill Manager – Pumphreys, Thornaby

- Harry Parsons marries Prudence Winifred Hackworth

- And much more…

WHO WAS JOAN HACKWORTH WEIR?

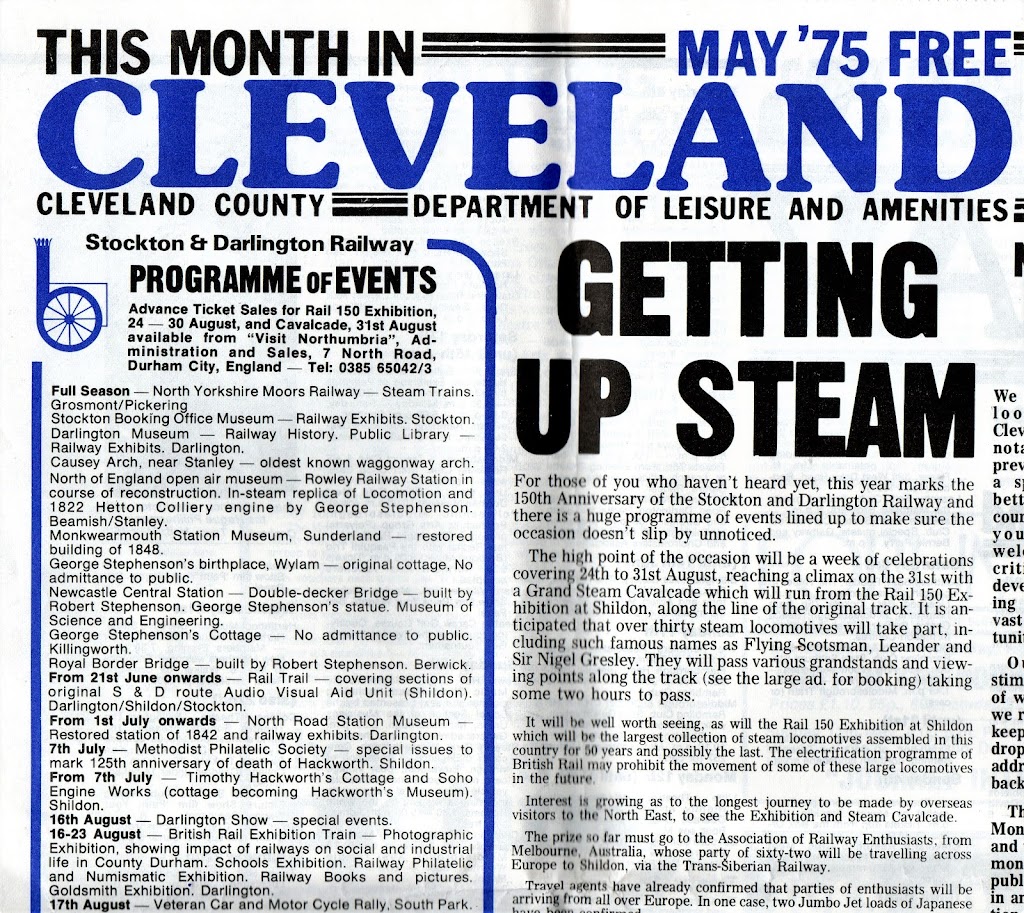

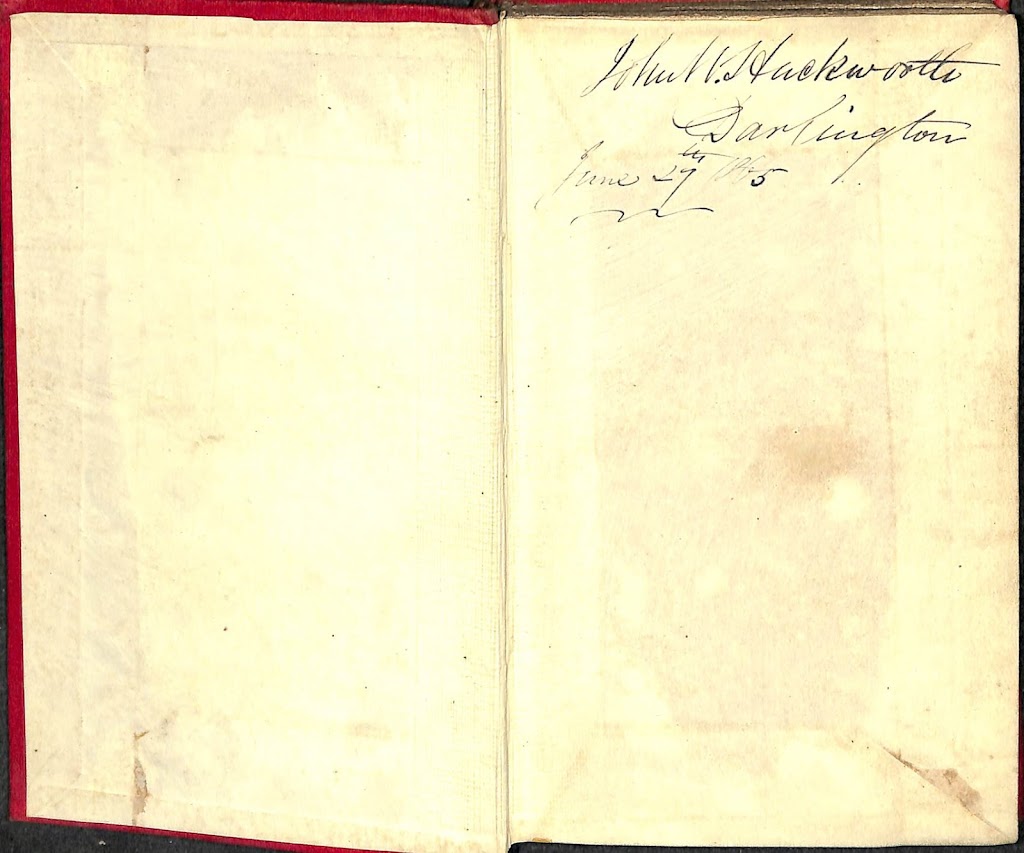

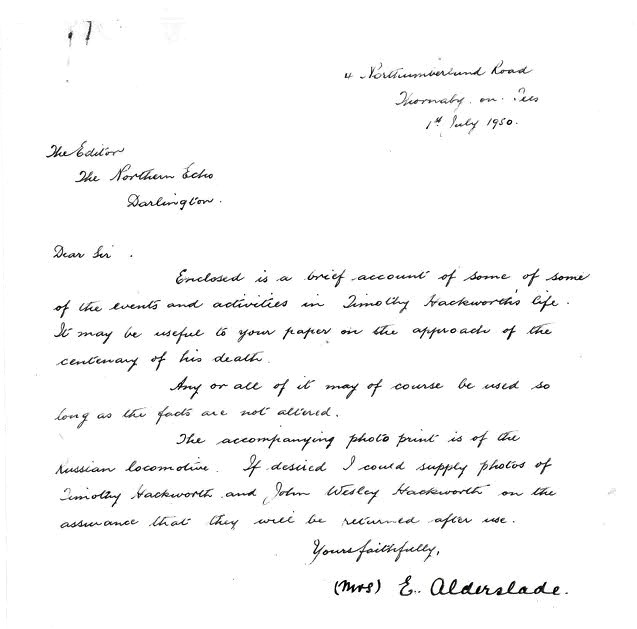

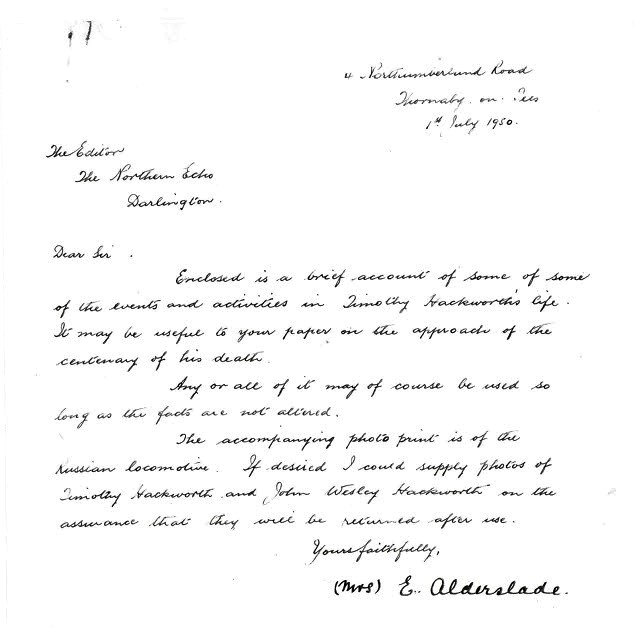

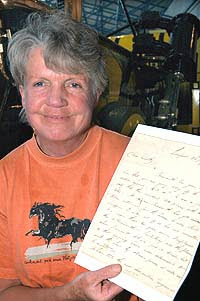

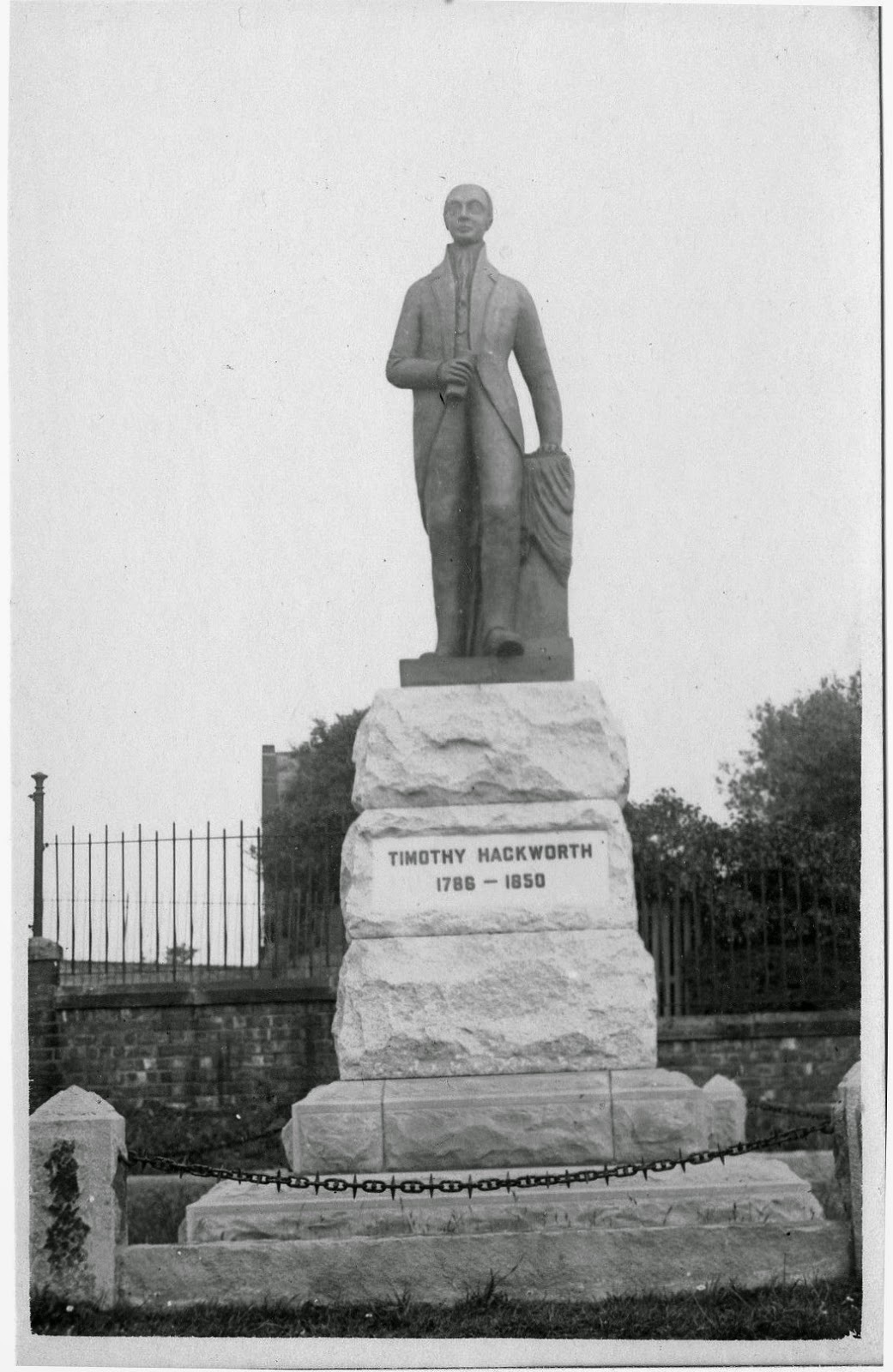

Joan Hackworth Weir nee Parsons was the great great granddaughter of Timothy Hackworth through Timothy’s son John Wesley Hackworth. Born at 43, Stephenson Street, Thornaby on Tees in September 1920, she appeared with the Hackworth relatives as a 5 year old in the Northern Echo during the 1925 Centenary of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and as this site shows, kept a goodly amount of the Hackworth archives, handed down to her through the John Wesley Hackworth line.

|

A five year old Joan Hackworth Weir nee Parsons centre

during the 1925 Stockton and Darlington Railway Centenary. |

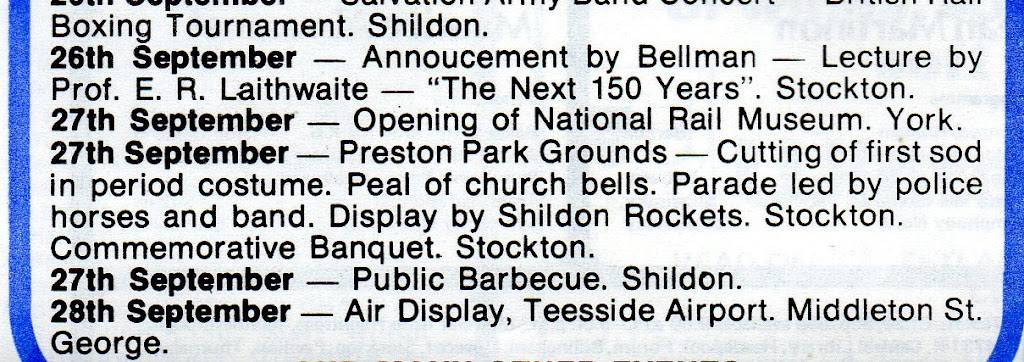

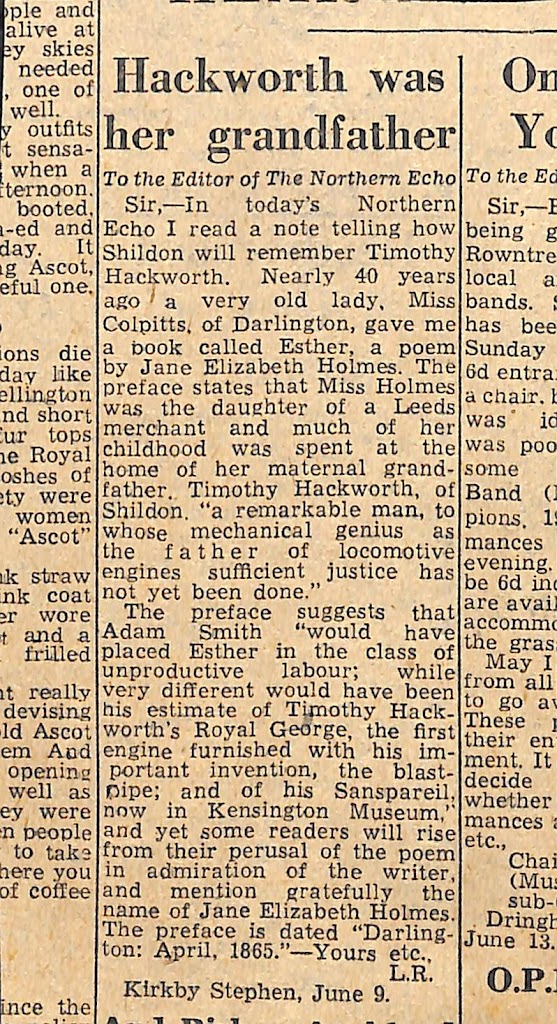

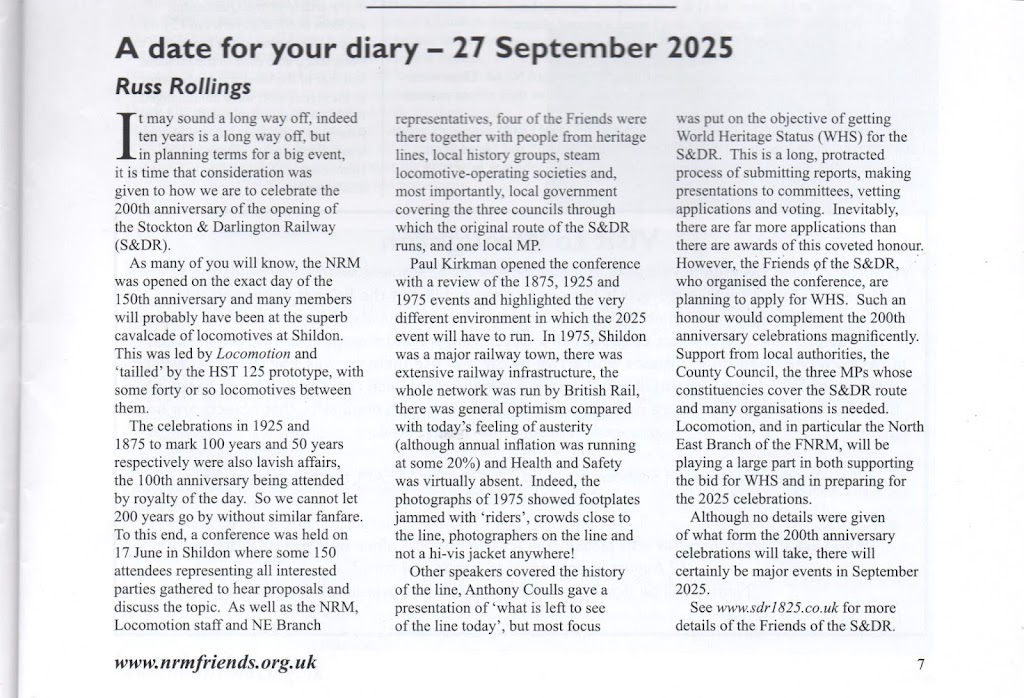

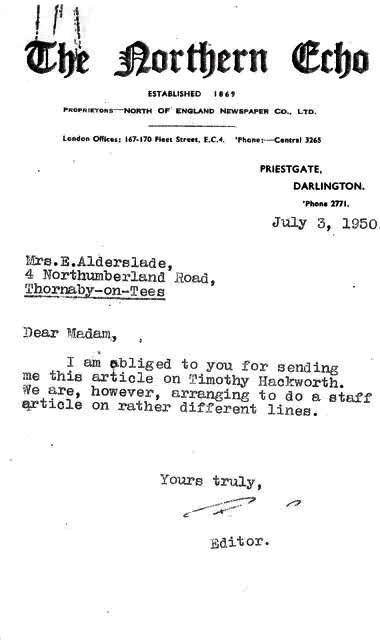

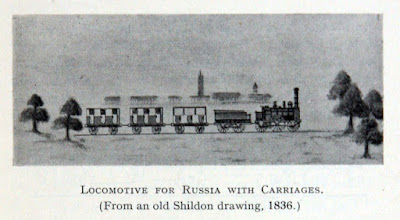

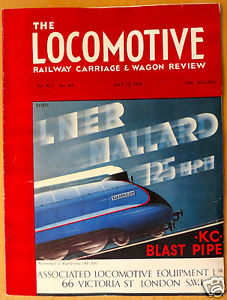

‘Blast Pipe Letters’

Joan’s archives included material now referred to as the ‘Blast Pipe Letters’ from George and Robert

|

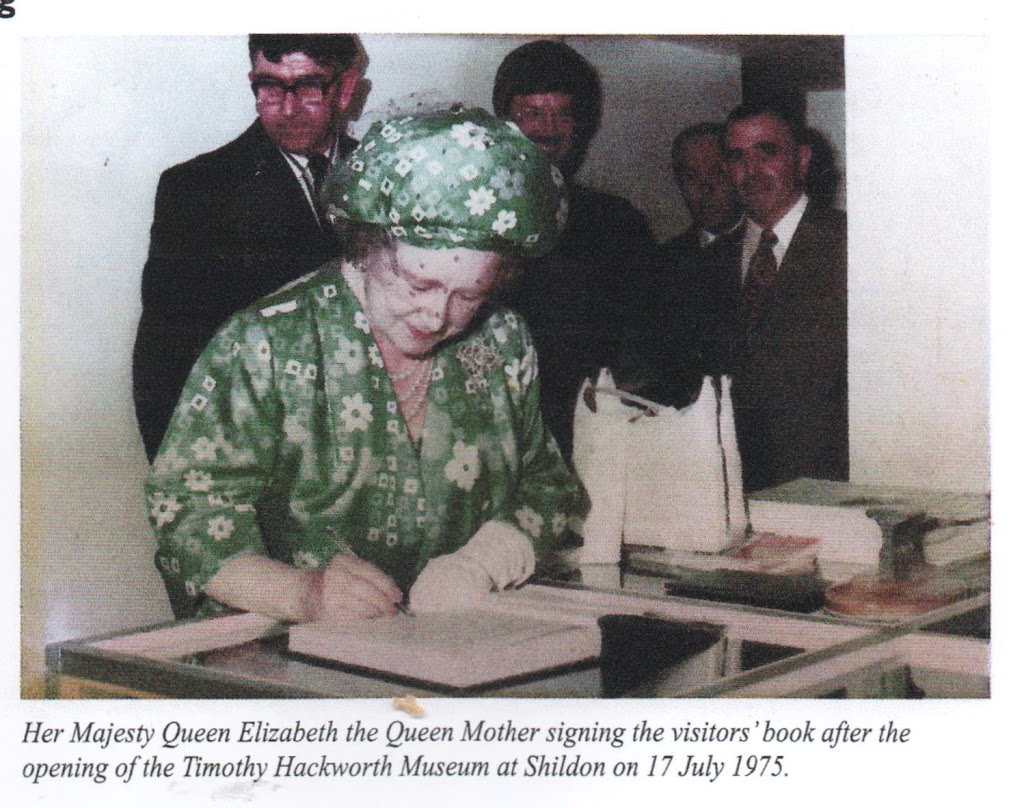

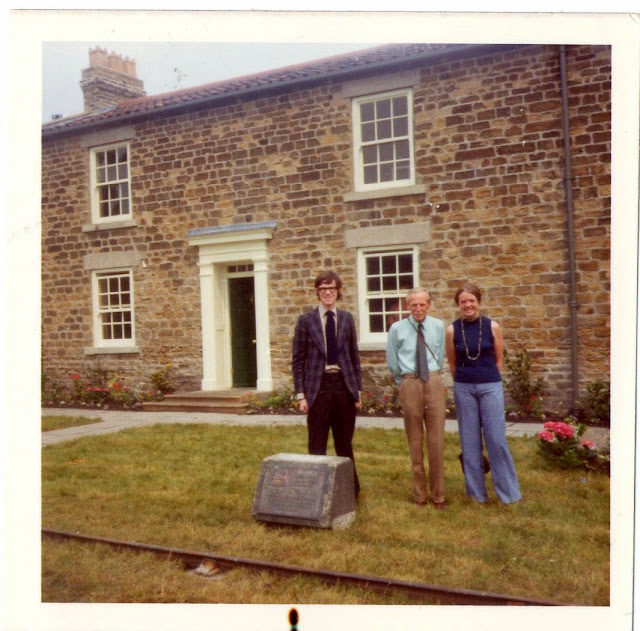

Joan, in pink, at the opening of the Timothy Hackworth Museum

Shildon 1975 with daughter Margaret, Ulick Loring etc. |

Stephenson (on this site) that purport to prove that Timothy had the ‘Blast pipe‘ before the Stephensons on the Royal George and before The Rocket. The family were custodians of this material and the archives show that they discussed the content with various magazines and newspapers along the way as well as providing access to Robert Young, the Hackworth descendant who wrote Timothy Hackworth and the Locomotive. The letters were donated to NRM at Shildon in 2004 via her cousin Jane Hackworth Young and caused much debate among Locomotive historians.

Her lineage on the Hackworth side was Timothy Hackworth – John Wesley Hackworth – Albert Hackworth and Prudence Winifred Hackworth who married Harry Parsons in Stockton on Tees. Joan married John Weir, a soldier based originally at Fort George in Scotland. From Albert Hackworth onwards, the family lived in Thornaby on Tees where Joan, a Cleveland County librarian, campaigned for the original Thornaby library to remain open. After marriage, the family moved to Stokesley and latterly to Great Ayton in North Yorkshire. She had one daughter – Margaret Weir and four grandchildren. Joan passed away in her 80’s in 2007.

THE INTERVIEW

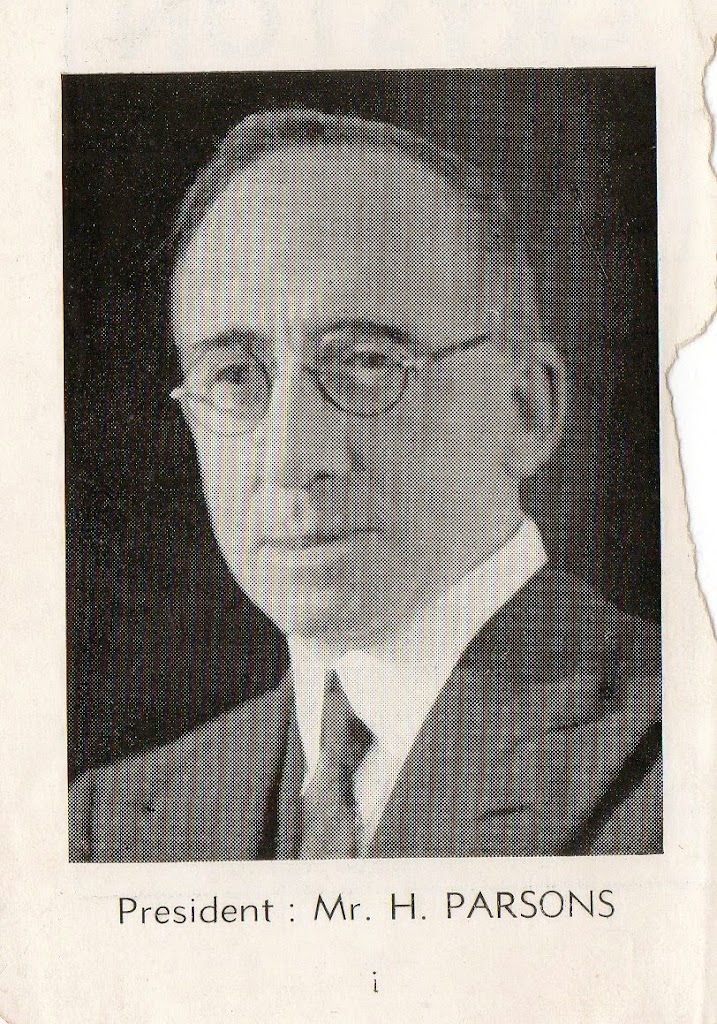

Joan was the daughter of Prudence Winifred Hackworth and Harry Parsons, who at the time of Joan’s birth, was an assistant foreman fitter at the Bridge works, Head Wrightsons. We asked her to tell us about her father’s side of the family first – The Parsons.

“Henry Parsons was my great granddad and one of 5 brothers who came north from Staffordshire during the Industrial Revolution to make their fortunes in the Iron and Steel industry. They settled in Stockton in Castlegate and Thistle Green and other parts of Teesside and they all had biblical names like Elijah, Eli and Daniel.”

Martin Parsons adds “Their paternal line can be traced to the Parsons of Baptists End, Netherton, Dudley who were mostly Ironworkers and many of them migrated to the North East in the 1800’s when a rich seam of iron ore was discovered in the Cleveland Hills, particularly at Eston near Middlesbrough. Dudley, it lay in a small enclave of Worcestershire completely surrounded by Staffordshire. It is now part of the West Midlands“

Thanks to Martin Parsons Wikitree site we have the following profile of Henry –

Henry Parsons Profile

Born 1823 in Netherton, Nr Dudley. Moved to Stockton on Tees where he owned two pubs and various properties in the Castlegate and Thistle green areas of Stockton all of which were redeveloped in the 1970’s. Henry was Son of Thomas Parsons and Sophia Whitehouse. Husband of Hannah Maria Roper, born 1836 in Dudley and died February 1905 in Thornaby. They married July 10, 1854 in St Thomas, Dudley, Worcestershire, England. Brother of William Parsons, William Parsons, Samuel Parsons, Thomas Parsons,Thomas Parsons, Phoebe Parsons, Mary Ann Parsons, Elijah Parsons, Daniel Parsons, Nanny Parsons, Eli Parsons and Rosanna Parsons. Father of Eli Parsons, Daniel Parsons, Henry Parsons, John Parsons and David Parsons. Died 1913 in County Durham. Presumably Stockton.

Joan continues –

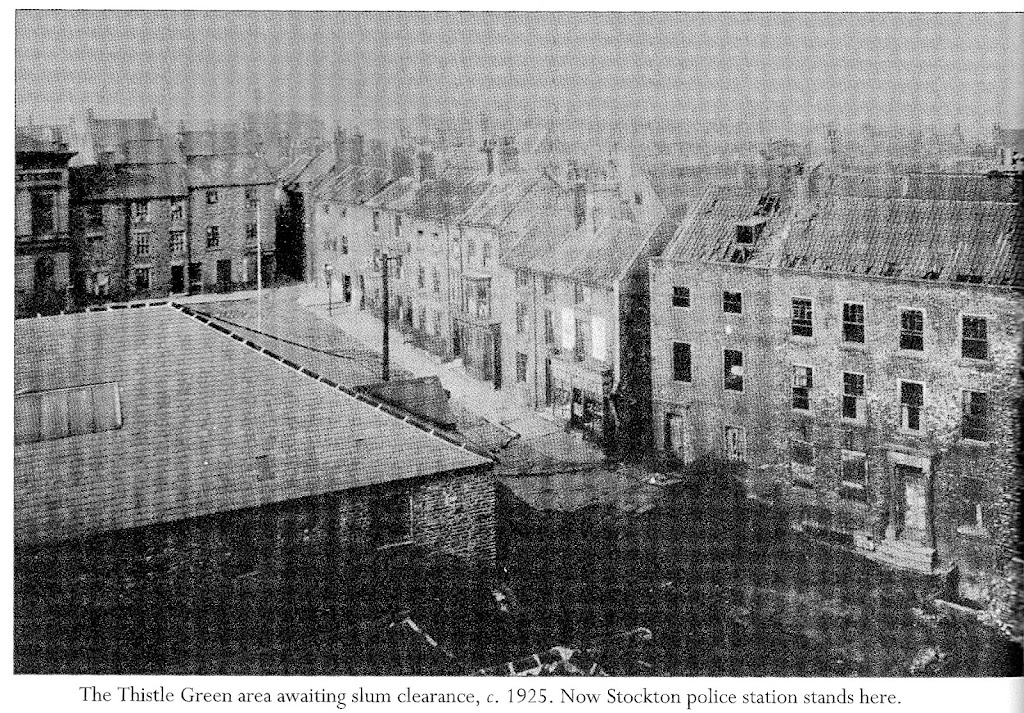

“The Swallow Hotel site is in Castlegate, roughly where Stockton Castle used to be and it was in that area that the early Parsons family settled in Stockton. They were located mainly in and around the High Street before it was redeveloped. It was a wider area than just the Swallow Hotel though, taking in Thistle Green where the library and police station now are..

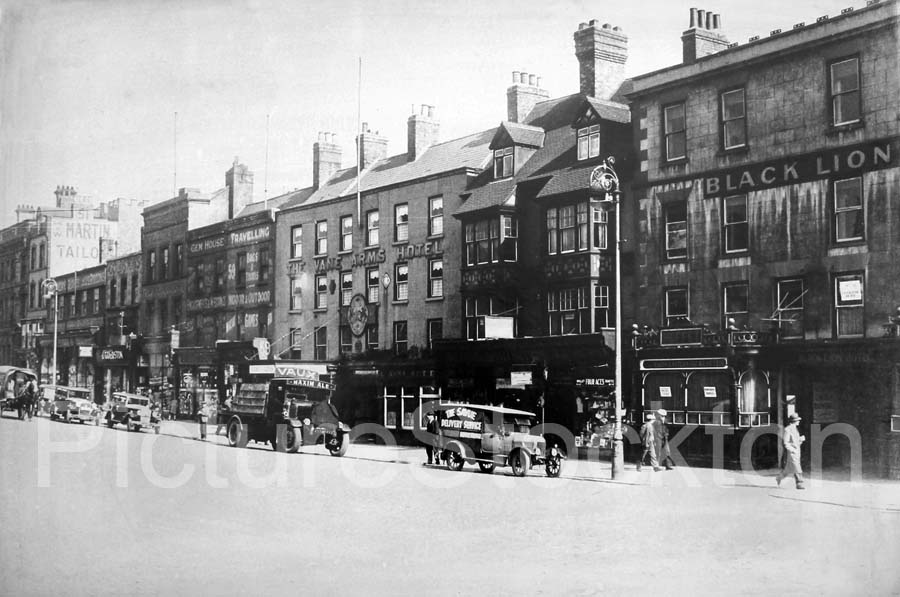

The alleyway down the side of the Swallow was called Castlegate. When my father (Harry Parsons) was a kid, the gates were still there. There were lots of small streets and alleyways and 2 or 3 old pubs and one called the Vane Arms. The Vane family were part of Lord Londonderry‘s family.

Castlegate is also where my sister’s husband’s family had their workshop – they were Cabinet Makers and Joinery. (Joan’s sister / Harry Parsons daughter) was Margaret Ruth Estelle Ferguson (nee Parsons) and her husband Donald Ferguson. There were other little businesses in Castlegate including a Locksmith, Tripestore etc. When they decided to redevelop Stockton High Street area in 1970, all of the people were offered new premises but none of them could afford the rent!!

They knocked all that property down on the site of what is now the Swallow Hotel, and in my time it was also the location of the Empire Cinema for years and years. The whole of the property along the side of the High Street where Boots and Woolworth were latterly was knocked down. (as can be seen in the photo below).

View from the south end of the site looking north towards Finkle Street –

The Vane Arms and The Royal Hotel were there and the Royal Hotel was where I had my wedding reception. The Vane Arms had a particularly interesting frontage but they swept it all away. It was outstanding.

|

| Royal Hotel Stockton High Street. |

Henry Parsons, owned property on Stockton High Street and Thistle Green. He was quite comfortably off.

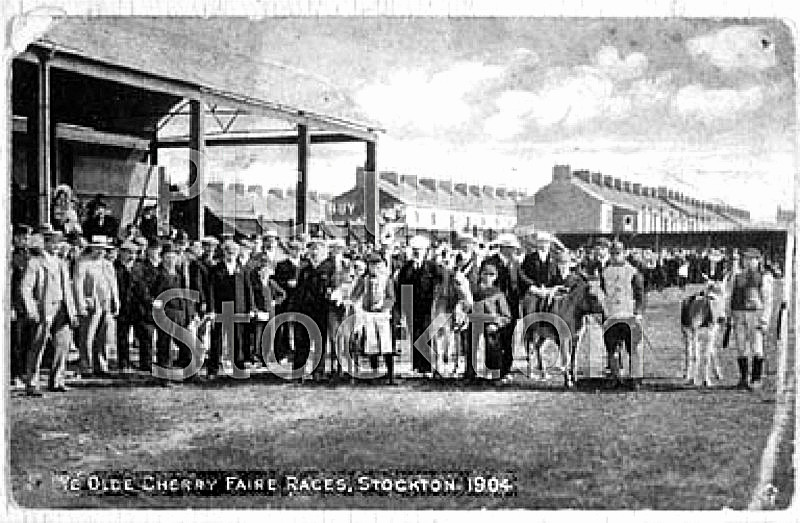

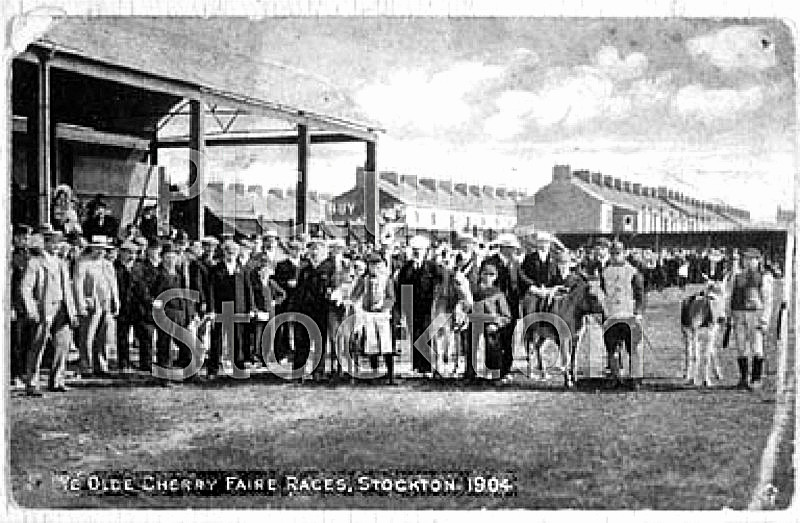

Cherry Fair Day

They used to have a Cherry Fair Day with a Donkey Derby. The Donkey Derby was on Stockton High Street and it was a jollification, everyone enjoyed it. And if Henry, didn’t make a £100 on Cherry Fair Day, he was disappointed. (The implication is that he was never disappointed!). Considering that a pint of beer cost 1d penny back then, it took some doing! Obviously he wasn’t hard up for a penny and he owned all this property.

|

| Cherry Fair races 1904 |

My grandfather (John Parsons) knew some of them quite well. There were two sisters who were my father’s friends and they lived in Stockton. One of them was married and had 2 sons and they used to be at my grandmothers sometimes and helped to entertain me as they were a bit older.

The sisters were my father’s great aunts and one of them was a Methodist at Fairfield Chapel.

Of the brothers Daniel Parsons was the youngest and was the father of my father’s organist. My father, Harry Parsons, had a band who played in the front room at Thornaby on Tees (Mansfield Road) – a classical quartet or quintet with piano. Harry played double bass in this classical ensemble. Mostly popular classical tunes.

This made Harry Parson‘s organist my grandfather’s cousin. Harry Parson’s organist and Joan’s dad, were approximately the same age and although they were the same age, they were of different generations as one was the youngest of the lot that came up from Staffordshire.

When my father was little, his grandfather Henry would take him to Fairfield to visit one of his brothers. My father said they had a beautiful garden with strawberry baskets in the summer but he wasn’t big enough to pick them but he used to lie down on his tummy and bite them off with his mouth! Harry’s mother (Lily Parsons nee Faith) would have been quite cross at the mess he was in because she was notoriously strict, so the aunts had to tidy him up before he went home!

Burning the Deeds!

It was great grandfather Henry Parsons who owned the pubs. Something happened – one day he came home very drunk and in a terrible mood and took all the deeds to all the property he owned and burnt them!

Now then, when it came to the time that all that property in Stockton was being redeveloped years later, if it had still been in the family, it would have been worth something. Oddly enough when my father was young, some people came to the house to offer to pay rent on the property that my great grandfather owned but they couldn’t take the money as they had no proof of ownership! The property that he owned that they offered to pay rent for was in the Thistle Green area of Stockton, which is now where Stockton Police Station and the library are.

My grandfather, with some of the cousins, thought they should contact a solicitor to see where they stood about the property and the solicitor said they would have to research all of the relatives dates and birth since, before they could put in any claim. They did this as far as they could but one relative was missing and that was it! They didn’t get a penny and eventually, by default (or as Joan put it by devious means!) all that property became the property of the solicitors!.

Anyway that’s just one little family story!

John Parsons

My grandfather (John) spent his childhood in one of Henry’s the pub and grew up running around the cellar where the beer barrels were kept, licking the drips off all the beer barrel taps. Later, in his 20’s he had a very nice voice and joined the Apollo Male Voice Choir.

Thanks to Martin Parsons Wikitree site we have the following profile of John Parsons.

“Born 1865 in Netherton, Worcestershire, England. Son of Henry Parsons and Hannah Maria Roper. Brother of Eli Parsons, Daniel Parsons, Henry Parsons and David Parsons. Husband of Lily Jane Faith, born about 1867 in Stockton on Tees, daughter of Thomas Faith and Anne Faith.

They married February 1889 in Stockton on Tees, Durham. Father of Ruth Parsons and Harry Parsons. Died date and location unknown. Presumably Thornaby on Tees.”

|

| Lily Jane Faith (Parsons) |

My grandmother on the Parson’s side was Lily Jane Faith. They were all steeped in music and taught the piano and would mend violins. My great grandfather on the Faith side was. Thomas Faith was a violin maker. He went to Whitby and met the daughter of a well off shipping family – Anne Faith whose maiden name was Gibson and they eloped in a coach and four to Stockton and got married. Her father (a Gibson) was a Whitby Whaler who lived in, we think, Stephenson Yard near the old part of the Whitby harbour early 1800’s. Grandmother Lily Faith married John Parsons, Harry’s father.

When John Parsons was a lad, he used to help the Doctor as an errand boy, delivering medicines because doctors back then made them themselves. John was very interested in medicine and would have liked to have been a doctor but his father wouldn’t pay for him to be a doctor and sent him to work in the ironworks at 9 years old. He was self educated and actually quite well educated. He worked in the ironworks on and off all his life as a labourer really and never apprenticed.

It was through the course of his music that he met Lily Faith and asked her to marry him. Somehow he became a Quaker, possibly because grandmother Faith was a Quaker. She said she wouldn’t marry him unless he became teetotal and he had to agree to sign the pledge. So he signed the pledge and used to run past all the pubs so he wouldn’t be tempted to go in!

When the Quakers first came to Stockton they started a school to teach adults to read and write. John joined in with all of this. John and Lily were married in February 1889 and as far as I know, had a Quaker marriage. He always wore a wedding ring, a heavy gold band which was uncommon in those days.They got married they were only about 24 & 22. (When Joan was born (1920) Lily said ‘ she needn’t think she’s going to call me grandma” because she didn’t like to be called grandma at a relatively young age! She would actually only be 31 in 1920.

Lily was ultra house-proud and John stuck to his word and never drank again but he was actually quite bigoted and when his daughter Ruth Parsons who was middle aged by then, was given a bottle of champagne, John forbade her to bring it into the house and so she took it round to her brother Harry’s house.

|

| Stockton High Street showing the old cobblestones. |

Anyway, John and Lily had a pretty rough time of it. When times were hard and he was out of work, they had to use the soup kitchen. They lived in a flat above a grocer’s shop in Stockton (on the way out of Stockton). The grocer’s shop was owned by John Towling. Harry was born in the flat above. Harry used to ride his tricycle down the centre of Stockton High Street, which was all cobbled at that time. He got up to all kinds of mischief like going fishing at Billingham Bottoms and bringing home a pail full of newts. Lily wouldn’t have them in the house and poured them down the drain and nearly broke his heart. She wasn’t very sympathetic like that.

Hard Times in Redcar

|

| A postcard sent by Harry Parsons to Prudence W. Hackworth |

Anyway when Harry Parsons was about 10 (about 1901), John and Lily hit a bad patch and decided to move to Redcar where Lily would run a boarding house. They did very well in summer but the winters were hard and Harry used to go down to the beach and help the fishermen bring in the boats and they used to give him a fish for his pains. That provided the family tea!

Harry went to a school run by the Methodist church and strangely, my mother (Prudence Winifred Hackworth (later Parsons) went to that school too. She had been sent to Redcar for the sea air to try and help cure her asthma but they never remembered knowing each other when they were children. Though later on when they had met and married, I remember them talking of about their individual memories of the school.

Harry would go out of school at playtime and go down to the beach and catch crabs both for the family and to sell. When Winifred went home, after her asthma was better, the Parson family were once again in a pretty bad way.

|

| Stockton High Street Hirings Day 1909 |

About 1901, at Christmas, John Parsons had gone to Stockton to see if he could find work of any sort at all. Lily didn’t have any money at all that Christmas and so there was no prospects of a Christmas dinner. However she was a woman who could make do with very little. So she must have been pretty desperate, the children (Harry and Ruth) would be about 10 and 11 at that stage and old enough to know what the situation was. Lily was a Quaker (and Harry said that this was one of his vivid childhood memories) – The house they lived in Redcar had 14 rooms. Lily took them into the kitchen and the 3 of them knelt down in front of the fire and prayed that the father would come back with something. Afterwards, they went to meet John off the last train back from Thornaby which arrived about midnight.

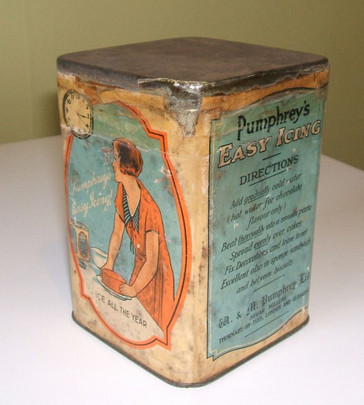

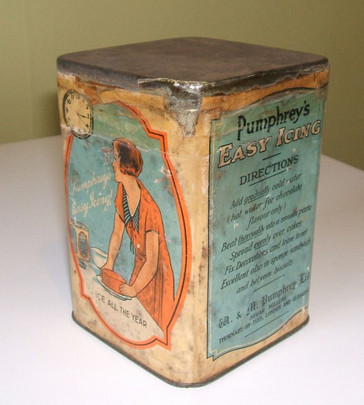

Pumphrey’s Sugar Mill

This was Christmas Eve and the shops used to be open until midnight then. They met him off the train and said ‘Have you got anything?‘ and he said “I’ve got a promise of job at Pumphreys (the Sugar company in Thornaby) and I’ve got an advance of a couple of shillings” and so they went to the only butchers that was still open and all they had left was a set of giblets and Lily made a pie of these and that was their Christmas dinner.

They moved back to Thornaby in the new year and John got his job at Pumphreys as a Sugar Mill Manager and there was a house that went with the job and they stayed in that house up until Joan’s lifetime and Joan was actually born in that house in 1920, in Mandale Road in Thornaby, behind Thornaby town hall.

The Pumphrey family were all Quakers and that’s how he got the job. He stayed there a very long time but eventually left and Joan thinks that is because of some disagreement with the Pumphrey family.

The last person to run Pumphrey was the youngest Pumphrey daughter Ruth Waters who lived in Great Ayton and she did some amazing black and white sketches which they used to sell at the Friends School in Great Ayton as Christmas cards. The Quakers had an adult school at Stockton and those who were educated helped to teach those who weren’t. John was very well read and used to help there. He’d read all of Dickens, the Bible and Shakespeare. He read any good book that came out. He was a quiet man but could hold his own in a conversation and was very well respected. On Winifred’s and Harry’s marriage certificate, John signed himself as Sugar Mill Manager and so was still there at the time, around 1919.

The last person to run Pumphrey was the youngest Pumphrey daughter Ruth Waters who lived in Great Ayton and she did some amazing black and white sketches which they used to sell at the Friends School in Great Ayton as Christmas cards. The Quakers had an adult school at Stockton and those who were educated helped to teach those who weren’t. John was very well read and used to help there. He’d read all of Dickens, the Bible and Shakespeare. He read any good book that came out. He was a quiet man but could hold his own in a conversation and was very well respected. On Winifred’s and Harry’s marriage certificate, John signed himself as Sugar Mill Manager and so was still there at the time, around 1919.

Harry Parsons and Prudence Winifred Hackworth

Thanks to Martin Parsons Wikitree site and Ulick Loring’s Hackworth site we have the following profile Harry Parsons –

of

Born about 1891 in Stockton On Tees. Died 1968. Son of John Parsons and Lily Jane Faith. Brother of Ruth Parsons. Father of Joan Hackworth Weir nee Parsons 1920 – 2007 and Margaret Ruth Estelle Ferguson nee Parsons (1932 – 72 – and a Hackworth. Grandfather of Margaret Weir bn 1956. Great Grandfather of Kieron and Tristan McGarry and Kyle and Kristian Teasdel. Married to Prudence Winifred Hackworth Thornaby 1919. Prudence Winifred died Thornaby 1956 and was the daughter of Albert and Esther Hackworth, Granddaughter of John Wesley Hackworth and Great granddaughter of Railway pioneer Timothy Hackworth.

Lily the Midwife – The birth of Joan Hackworth Parsons (later Weir)

When Winifred was quite advanced in her pregnancy, Joan was lying on a nerve or muscle so that Winifred could hardly walk and so grandma Lily was the kind of person who before midwives helped at births and deaths and things like that and that’s why Winifred was staying with Lily at the time. Winifred had a pretty tough time of it and after 3 days in labour the doctor said “I’ve got to save the baby or the mother and I don’t think I can do both.” Luckily, however, both mother and baby survived. Joan’s was a forceps birth. When Harry first saw her, her face was very squashed, one of her ears was stuck back and so they used sticking plaster and it was bent forward and her nose was bent to the side, so they fixed it with sticking plaster too. The sticking plaster worked because Joan’s daughter remembers her with her nose and ears in the right position!

“We lived in Gordon Terrace, Thornaby, in the last row of houses. There were just fields behind our house at that time – the early 1920’s – right up to where the airfield is now.

My mother was a Prudence Winifred Hackworth and my father was Harry Parsons. His mother was Lily Jane Faith who married John Parsons, so the Hackworths side came in with my mum and dad. Winifred was the granddaughter of John Wesley Hackworth.

How Did Harry and Prudence Meet?

|

| Prudence Winifred Hackworth / Parsons |

Ah! Well, there again music played a large part because after the grandparents moved back to Thornaby, my father left school when he was only 13 and he kept going down to Head Wrightsons to ask for a job. He went to the tool room foreman and he kept saying “Why do you want a job?” and he said “I want to be an engineer“. Harry kept turning up with great regularity and eventually the foreman called Mr Marshall gave in and gave him a job. So he started an apprenticeship at 14 and he was so small at that stage they gave him a box to stand on, so he could reach the the work desk. When fully grown he was 5’10” tall. He wasn’t exactly small but he hadn’t really grown at that stage.

Anyway, during this period Ruth, his sister played piano and he learned to play violin and he had a cousin called Bert who actually had an organ at home. I’m not talking about a little Harmonium – it was massive and in the sitting room. Bert was very involved with the church music and Sunday School – he was my father’s cousin and they lived in Scarborough Street in Thornaby and because they had this musical thing in common, my father sort of gravitated towards the Methodist Sunday school and by that time the grandparents didn’t mind so long as he was going to church.

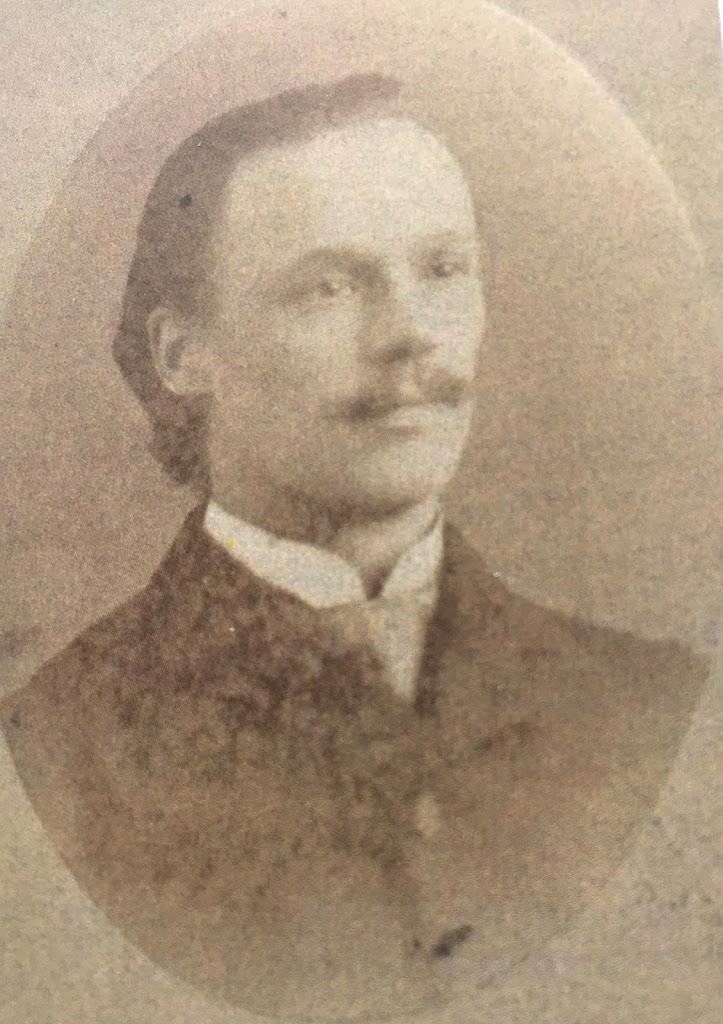

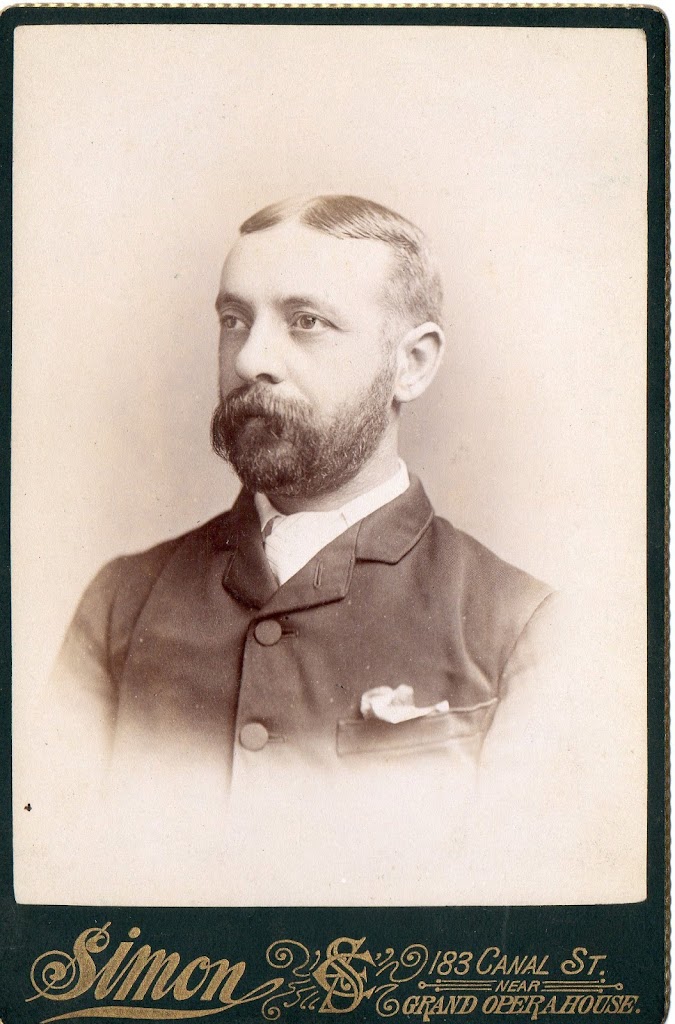

|

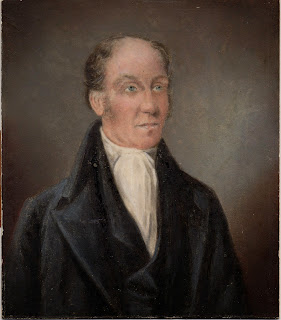

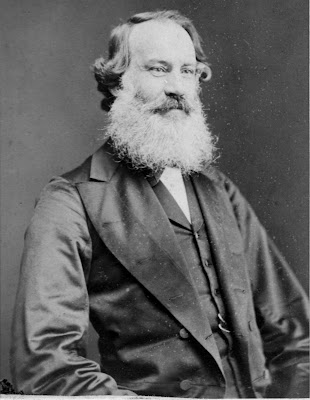

| Albert Hackworth |

The Sunday school had an outing, like Sunday schools do and because the Hackworths were all Methodists, because Timothy Hackworth was a personal friend of John Wesley (John Wesley would stay at Timothy’s when he was in the area). My Mam (Prudence) went to the local Methodist church – people went to Sunday School in those days until they were 16 or 17 and they had this outing. My Dad was 16 and my Mam 15 and he pushed her on a swing and I think that was how they met but of course Thornaby wasn’t very big place and everybody sort of knew everybody else and of course the Hackworth family were well known just before the first World War because of Timothy Hackworth. By this time my mother’s father, Albert Hackworth (John Wesley Hackworth‘s son) had died and her mother Esther Hackworth nee Williams,was a widow living on what money she had. She was the relative that came from Wales.

When my mother’s parents – Albert and Esther – were just married, they lived in Sunderland and they didn’t arrive in Thornaby for a while and of course, they were the first Hackworths to move to Thornaby. Anyway, that’s how my mum and dad met. At the church they went around as a group of boys and girls like kids do but eventually, having realised her mother was hard up, she realised that security was important and said she would marry him when he had a £100 saved up. That was a fortune then and so he decided he would go to Canada and make his fortune. So off he went with his cousin Bert and one of the Williams family, my Mum’s uncle. They all went and my father stayed there and had a pretty hard time of it and was down to his last dollar, almost before he got any work there. He played violin over there but not for money but he said if you can play an musical instrument you can always find friends who were interested.

Anyway, he just about got his £100 saved up and the 1914 war broke out and they advertised in Montreal for people to volunteer and come over here in what was called the Workman’s Army. They wanted skilled workers, so he thought it was a way of getting home, so he signed on for this and came home and was dumped in Barrow in Furness and sent to work at Vickers Armstrong. He was working on rifling for the big guns on ships and on things for submarines. he would only be 23/24 i suppose and of course all his friends were going to war and so he volunteered for every service in term and as soon as they asked him what his occupation was, they turned him down because he was too valuable where he was. He was working on the rifling that goes inside a gun that makes the bullet or whatever it is spin and working on those big guns on navel ships. he had a terrible time there in Barrow in Furness because they dumped ever so many thousand men there and they worked different shifts and as one got up out of bed another came home from work and fell into the same bed and having grown up with his mother, Lily Faith (Parsons) to whom cleanliness was next to godliness, it was hell.

(An interesting article on Barrow in Furness during World War 1 from the Independent) http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/world-history/history-of-the-first-world-war-in-100-moments/a-history-of-the-first-world-war-in-100-moments-the-munitions-workers-who-made-the-british-government-tremble-9487877.html

There was one place he was so crawly that he bought himself a brand new set of clothes, went to the local Rice Pudding Lin, Kipperdelly Avenue and so on, and they knew where these places were.

|

| Vickers Armstrong, Barrow in Furness |

bath house, got bathed with disinfectant, wrapped the clothes in a sack and said to the attendant, you can burn those and moved out and found himself new lodgings. There was another place he wakened to find the person he was sharing a bed with had a TB haemorrhage and he left there and didn’t go back and the food was shocking because they weren’t paid very much – they were billeted like soldiers and he said the names of the streets got known because the housewives used to gang up and use certain recipes and foods to feed them. there was

Well eventually he asked if he could get transferred to Head Wrightsons where he served his apprenticeship

and that was how he got back to Thornaby and Head Wrightsons were producing for the war and had women working there for the 1st time, making bombs and shells amongst other things. And so he was lucky in a sense that he didn’t see active service but he did want to go and because of that, dozens of their friends never came back. He had a cousin, they never found him – just lost. It was pretty awful.

My Mam’s name was Prudence but everyone called her Win. If anyone was ever called Prudence, it was my Mam, she wouldn’t marry him until he had a £100 saved up and then she wouldn’t marry him while the war was on, so they didn’t get married until he was 26 and she 27 in 1919.

The £100 bought them a dinning room suit and the rest of the furniture was inherited from her mum’s house, because after mother died, the three girls all lived together – Mary, Esther and Winifred – 3 Hackworth sisters. When my Mam and dad got married, Essie got herself a job, Essie and Mary were both teachers.

|

| Esther and Mary Hackworth 1925 |

Mary was teaching at Stockton and went to live with her great aunt and uncle. Essie got herself a job at a Hutton Henry in County Durham. However, she can’t have stayed there a long time because I never remember a time in my early life when Aunt Essie didn’t live with us, until she got married when I was about 7 years old. Aunty Mary died, she had a weak heart and when she was only 30 and I was 5, she got rheumatic fever and she died of it. Their brother, the oldest one who was called Albert, named after his father, emigrated to Canada and started at an engineering company called the Worth Engineering Company. It was someone else whose name was Worth and he was victim of sugar diabetes and died of it before insulin was discovered. He died a few months before I was born – he must have died about 1920. So two of them died without being married and aunty Essie and Uncle Norman got married when I was 7 and they never had any family, so my sister and I were the only ones in this line, you see and then only me – it was shrinking and then expanded – it’s interesting – the thing that impresses me is – in a sense it depresses me a bit about now, is the fact that they all valued education and knowledge and thought it was important.

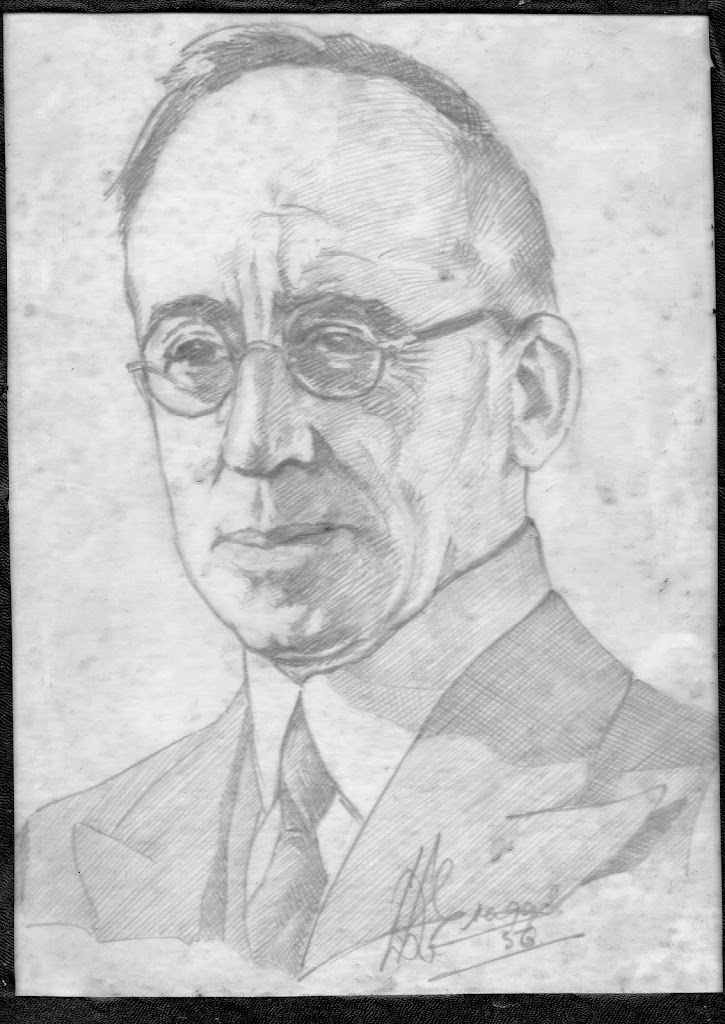

The Other Christmas Story

|

| Harry Parsons |

When I was 9 or 10 and the depression was on and a lot of men were out of work, The local Methodist Church had what was called a brotherhood which was a special event on a Sunday afternoon. There was an orchestra and volunteers and my father Harry Parsons used to play his violin there, well at Christmas.brotherhood decided they would use some of their funds to give men who were out of work a Christmas gift, to help the family through Christmas and they elected a committee and it was suggested that each family should be given 10/- and my father said “Well, surely we can do a bit better than that, we have on our committee a man is the manager of a Coop foodstore. He could arrange to have parcels made up to the value of 10/- in groceries and this would mean a lot to the families. The whole family would benefit.” So the committee agreed to do this. So then they said “We need volunteers to deliver these parcels” so my father volunteered to deliver some of the parcels and went out one Christmas eve on a parcel delivery. He’d been to see one family that he was particularly sorry for, they had small children, the mother had been ill and the father was very worried and they were hard up and my father felt very sorry for them. So he came home and he had a chicken for Christmas and he said to my mother, I’m going to give our chicken away and he told my mother why and she didn’t object because she had a soft spot for the children and he gave it to this family who were very very grateful, because he remembered all those years ago when he nearly didn’t have a Christmas dinner because they were hard up. Back then, there used to be a postal delivery on Christmas day and that year some people that we knew in the country sent us a chicken – we’d never had one before from them and we never had one afterwards so we had our Christmas dinner after all! Call it providence or what you will but there you are!

It was Brenda and Sheila’s granny’s farm – I went to school with them. That’s where the chicken came from. Sometime before, my father had been ill and he’d lost the use of his legs and when he got better he went and stayed on the farm for a week to recuperate and they must have remembered and thought oh well, maybe they had the odd chicken that nobody had bought and just thought they’d send it.

|

| Clack lane Ends, Osmotherly |

The farm was at Clack Lane End, Osmotherly near Nether Silton. Brenda was only 10 when her father died and she passed her scholarship that year to go to the High School and Sheila and Joan came between them. Brenda was older and Sheila was younger. Brenda was at the High school (Constantine now part of Teesside University) in Middlesbrough. The boy, William, didn’t go to the High school and the grandmother mother had a 10/- widows pension which is all it was in those days and she ran a Corsetiere business, Spirella Corsets and they would them a chicken too. They always sent them one and other things they had and Mrs Sadler’s sister was married to the inspector of weights and measures, so he had a reasonably good job and no family and they used to buy the kids things like winter coats, the aunts and uncles, in the summer holidays and that was how I once went to visit them on the farm at Nether Silton, Clack Lane Ends, Near Osmotherley.

It was a beautiful day, from Stockton to Clack Lane end, one little pub there then. The girls came to meet me and then we had to walk and everybody in the fields said good morning and it seemed like a long walk. It wouldn’t be quite at Nether Silton but that was the address. There was an old granny who was at that time still unmarried. There were two unmarried brothers who did the outside farm work and they had one of these huge scrub white wood tables and a stone floor.

We had rabbit pie and I never liked Rabbit pie so I didn’t get to eat it. I don;t know what else we had but it was very nice. I had a lovely dinner there but was a bit timid of all the animals. They were used to them. They went to bring the horse in that had been working in the field, a shire horse and they rode on his back, both of them. The horse stopped in the middle of the duck pond. I suspect it was hot and the duck pond would be cool for its feet. It stayed there for a few minutes and kept patting its rump part saying ‘come on‘.

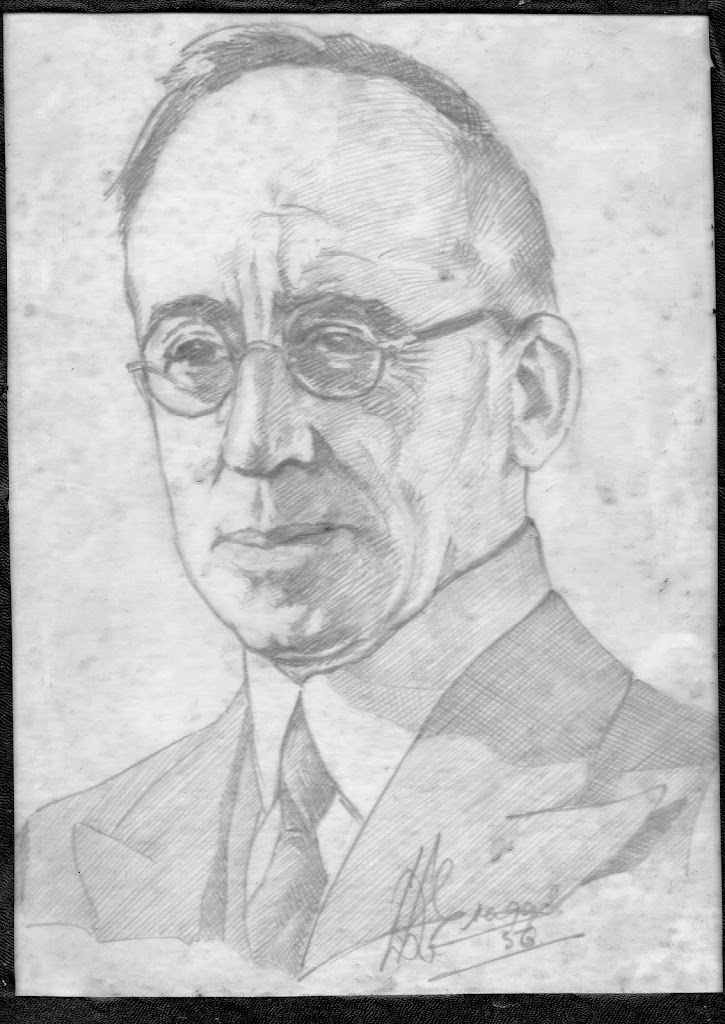

|

| A sketch of Joan’s father, Harry Parsons. |

|

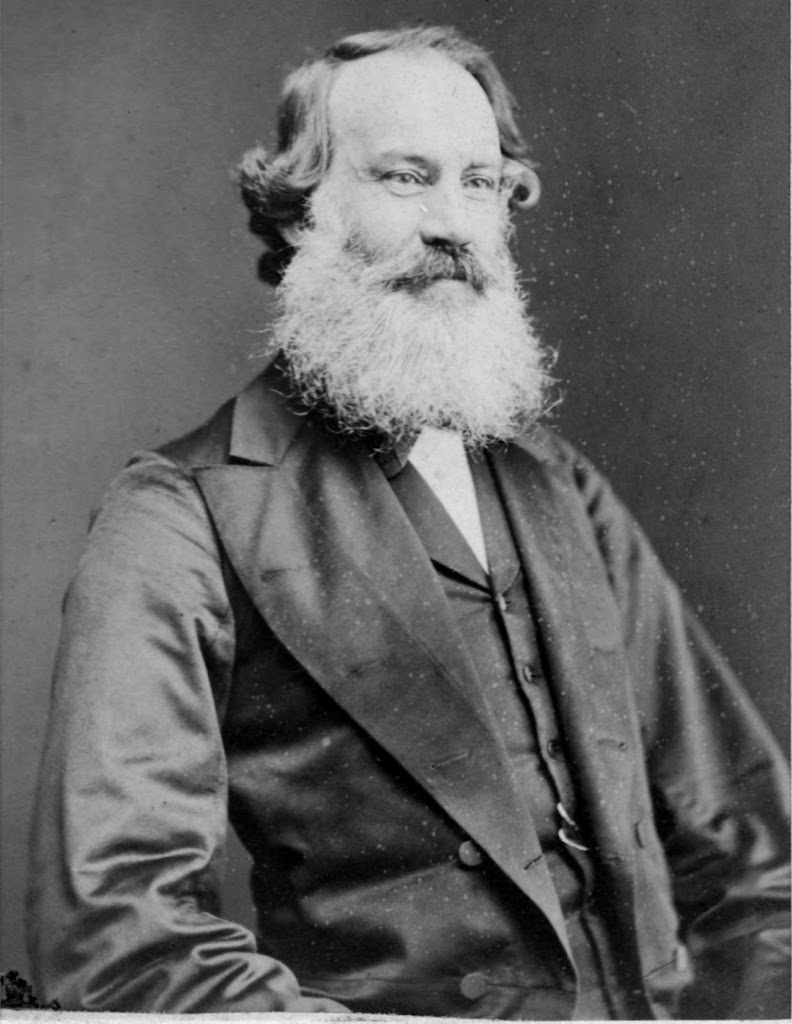

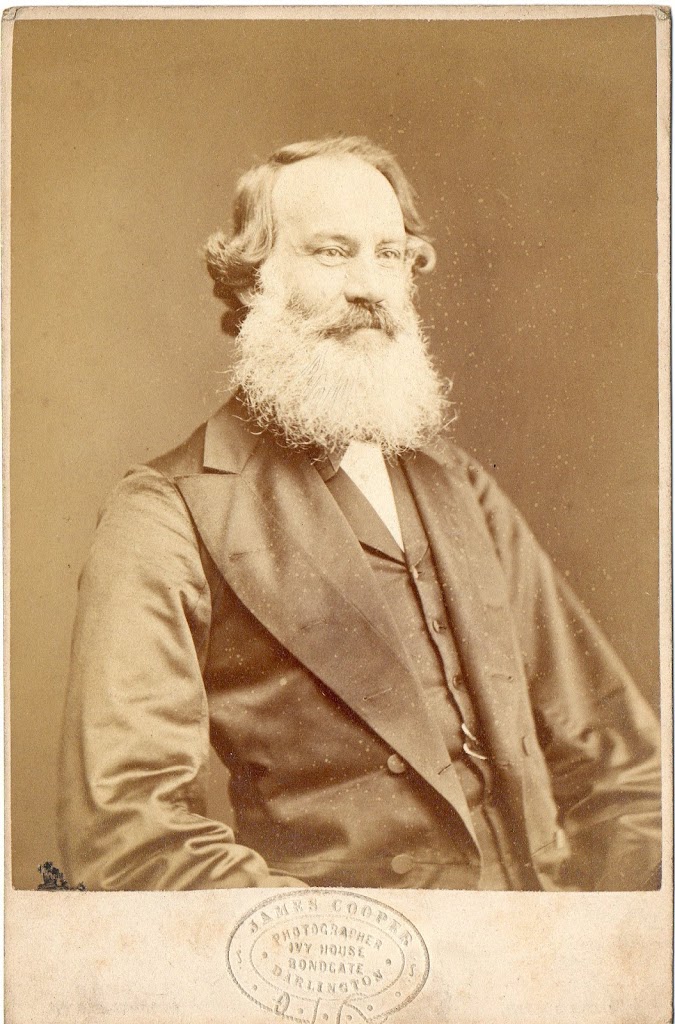

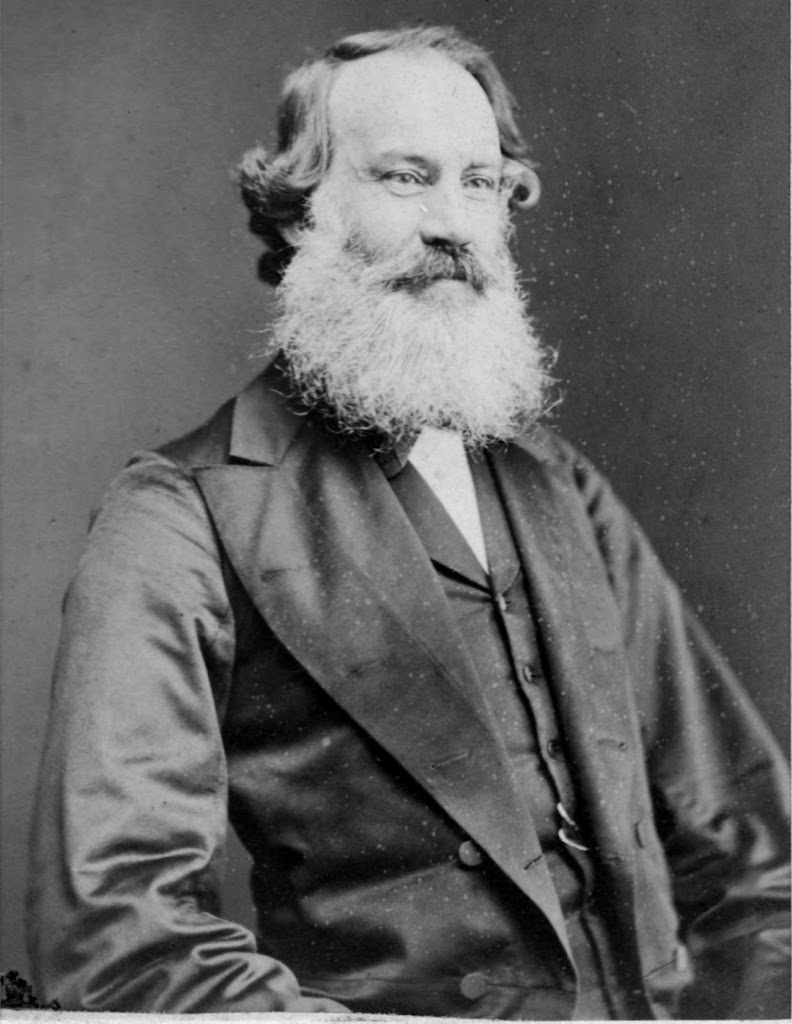

John Wesley Hackworth 1820 – 1891

Joan’s great great granddad

and Timothy Hackworth’s son. |

|

| John Weir as a young soldier at Fort George, Scotland. |